Briefly? The attempted coup is surrounded by so many events and characterized by so many nuances that entire books are dedicated to it. This was the first organized protest against serfdom in Russia, which caused a huge resonance in society and had a significant impact on the political and social life of the subsequent era of the reign of Emperor Nicholas I. Nevertheless, in this article we will try to briefly cover the Decembrist uprising.

General information

On December 14, 1825, an attempted coup took place in the capital of the Russian Empire, St. Petersburg. The uprising was organized by a group of like-minded nobles, most of whom were guards officers. The goal of the conspirators was the abolition of serfdom and the abolition of autocracy. It should be noted that in its goals the uprising was significantly different from all other conspiracies of the era of palace coups.

Salvation Union

The War of 1812 had a significant impact on all aspects of people's lives. Hopes arose for possible changes, mainly for the abolition of serfdom. But in order to eliminate serfdom, it was necessary to constitutionally limit monarchical power. The history of Russia during this period was marked by the massive creation of communities of guard officers, the so-called artels, on an ideological basis. Of two such artels, at the very beginning of 1816, the creator was Alexander Muravyov, Sergei Trubetskoy, Ivan Yakushkin, and later Pavel Pestel joined. The goals of the Union were the liberation of the peasants and the reform of government. Pestel wrote the organization’s charter in 1817; most of the participants were members of Masonic lodges, therefore the influence of Masonic rituals was reflected in the everyday life of the Union. Disagreements between members of the community over the possibility of killing the Tsar during a coup d'etat caused the Union to be dissolved in the fall of 1817.

Welfare Union

At the beginning of 1818, the Union of Welfare was organized in Moscow - a new secret society. It included two hundred people, concerned with the idea of forming progressive public opinion and creating a liberal movement. For this purpose, it was planned to organize legal charitable, literary, and educational organizations. More than ten union councils were founded throughout the country, including in St. Petersburg, Chisinau, Tulchin, Smolensk and other cities. “Side” councils were also formed, for example, the council of Nikita Vsevolzhsky, “Green Lamp”. Members of the Union had to actively participate in public life and try to occupy high positions in the army and government agencies. The composition of society changed regularly: the first participants started families and retired from political affairs, and new ones came to replace them. In January 1821, a congress of the Welfare Union was held in Moscow for three days, due to differences between supporters of moderate and radical movements. The activities of the congress were led by Mikhail Fonvizin and it turned out that informers informed the government about the existence of the Union, and a decision was made to formally dissolve it. This made it possible to free ourselves from people who entered the community by accident.

Reorganization

The dissolution of the Welfare Union was a step towards reorganization. New societies appeared: Northern (in St. Petersburg) and Southern (in Ukraine). The main role in Northern society was played by Sergei Trubetskoy, Nikita Muravyov, and later by Kondraty Ryleev, a famous poet who rallied the fighting republicans around himself. The head of the organization was Pavel Pestel, guard officers Mikhail Naryshkin, Ivan Gorstkin, naval officers Nikolay Chizhov and brothers Bodisko, Mikhail and Boris took an active part. The Kryukov brothers (Nikolai and Alexander) and the Bobrishchev-Pushkin brothers took part in the Southern Society: Pavel and Nikolai, Alexey Cherkasov, Ivan Avramov, Vladimir Likharev, Ivan Kireev.

Background to the events of December 1825

The year of the Decembrist uprising has arrived. The conspirators decided to take advantage of the difficult legal situation that arose around the right to the throne after the death of Alexander I. There was a secret document according to which Konstantin Pavlovich, the brother of the childless Alexander I, next in seniority behind him, renounced the throne. Thus, the next brother, Nikolai Pavlovich, although extremely unpopular among the military-bureaucratic elite, had an advantage. At the same time, even before the secret document was opened, Nicholas hastened to renounce the rights to the throne in favor of Constantine under the pressure of M. Miloradovich, the Governor-General of St. Petersburg.

Change of power

On November 27, 1825, the history of Russia began a new round - a new emperor, Constantine, formally appeared. Even several coins were minted with his image. However, Constantine did not officially accept the throne, but did not renounce it either. A very tense and ambiguous interregnum situation was created. As a result, Nicholas decided to declare himself emperor. The oath was scheduled for December 14. Finally, the change of power came - the moment that members of the secret communities had been waiting for. It was decided to start the Decembrist uprising.

The uprising on December 14 was a consequence of the fact that, as a result of a long night meeting on the night of 13 to 14, the Senate nevertheless recognized Nikolai Pavlovich’s legal right to the throne. The Decembrists decided to prevent the Senate and troops from taking the oath to the new king. It was impossible to delay, especially since the minister already had a huge number of denunciations on his desk, and arrests could soon begin.

History of the Decembrist uprising

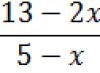

The conspirators planned to occupy the Peter and Paul Fortress and the Winter Palace, arrest the royal family and, if certain circumstances arose, kill them. Sergei Trubetskoy was elected to lead the uprising. Next, the Decembrists wanted to demand from the Senate the publication of a national manifesto proclaiming the destruction of the old government and the establishment of a provisional government. Admiral Mordvinov and Count Speransky were supposed to be members of the new revolutionary government. The deputies were entrusted with the task of approving the constitution - the new fundamental law. If the Senate refused to announce a national manifesto containing points on the abolition of serfdom, equality of all before the law, democratic freedoms, the introduction of compulsory military service for all classes, the introduction of jury trials, the election of officials, abolition, etc., it was decided to force him to do so forcibly.

Then it was planned to convene a National Council, which would decide the choice of form of government: a republic or If a republican form was chosen, the royal family should have been expelled from the country. Ryleev first proposed sending Nikolai Pavlovich to Fort Ross, but then he and Pestel plotted the murder of Nikolai and, perhaps, Tsarevich Alexander.

December 14 - Decembrist uprising

Let us briefly describe what happened on the day of the coup attempt. Early in the morning, Ryleev turned to Kakhovsky with a request to enter the Winter Palace and kill Nicholas. He initially agreed, but then refused. By eleven in the morning the Moscow Guards Regiment, the Grenadier Regiment, and the sailors of the Guards Marine Crew were withdrawn. In total - about three thousand people. However, a couple of days before the Decembrist uprising of 1825 began, Nicholas was warned about the intentions of members of secret societies by the Decembrist Rostovtsev, who considered the uprising unworthy of noble honor, and the chief of the General Staff, Dibich. Already at seven in the morning, the senators took the oath to Nicholas and proclaimed him emperor. Trubetskoy, appointed leader of the uprising, did not appear on the square. The regiments on Senate Street continued to stand and wait for the conspirators to come to a common opinion on the appointment of a new leader.

Climax Events

On this day the history of Russia was made. Count Miloradovich, who appeared before the soldiers on horseback, began to say that if Constantine refused to be emperor, then nothing could be done. Obolensky, who had left the ranks of the rebels, convinced Miloradovich to drive away, and then, seeing that he was not reacting, lightly wounded him in the side with a bayonet. At the same time, Kakhovsky shot the count with a pistol. Prince Mikhail Pavlovich and Colonel Sturler tried to bring the soldiers to obedience, but all attempts were unsuccessful. Nevertheless, the rebels twice repulsed the attack of the Horse Guards, led by Alexei Orlov.

Tens of thousands of residents of St. Petersburg gathered in the square; they sympathized with the rebels and threw stones and logs at Nicholas and his retinue. As a result, two “rings” of people were formed. One surrounded the rebels and consisted of those who came earlier, the other was formed from those who came later, the gendarmes no longer allowed them into the square, so people stood behind the government troops who surrounded the Decembrists. Such an environment was dangerous, and Nicholas, doubting his success, decided to prepare crews for members of the royal family in case they needed to escape to Tsarskoe Selo.

Unequal forces

The newly-crowned emperor understood that the results of the Decembrist uprising may not be in his favor, so he asked Metropolitans Eugene and Seraphim to appeal to the soldiers with a request to retreat. This did not bring results, and Nikolai’s fears intensified. Nevertheless, he managed to take the initiative into his own hands while the rebels were choosing a new leader (Prince Obolensky was appointed to them). Government troops were more than four times larger than the Decembrist army: nine thousand infantry bayonets, three thousand cavalry sabers were collected, and later artillerymen were called in (thirty-six guns), in total about twelve thousand people. The rebels, as already noted, numbered three thousand.

Defeat of the Decembrists

When the Guards artillery appeared from the Admiralteysky Boulevard, Nikolai ordered a volley of grapeshot to be fired at the “rabble” located on the roofs of the Senate and neighboring houses. The Decembrists responded with rifle fire, and then fled under a hail of grapeshot. Shots continued after them, the soldiers rushed onto the ice of the Neva with the goal of moving to Vasilyevsky Island. On the Neva ice, Bestuzhev attempted to establish battle formation and go on the offensive again. The troops lined up, but were fired at by cannonballs. The ice was breaking and people were drowning. The plan was a failure, and by nightfall hundreds of corpses lay on the streets and squares.

Arrest and trial

Questions about what year the Decembrist uprising took place and how it ended will probably not be answered by many today. However, this event largely influenced the further history of Russia. The significance of the Decembrist uprising cannot be underestimated - they were the first in the empire to create a revolutionary organization, develop a political program, prepare and implement an armed uprising. At the same time, the rebels were not prepared for the trials that followed the uprising. Some of them were executed by hanging after the trial (Ryleev, Pestel, Kakhovsky and others), the rest were exiled to Siberia and other places. There was a split in society: some supported the tsar, others supported the failed revolutionaries. And the surviving revolutionaries themselves, defeated, shackled, captured, lived in deep mental anguish.

In conclusion

The article briefly described how the Decembrist uprising took place. They were driven by one desire - to take a revolutionary stand against autocracy and serfdom in Russia. For enthusiastic young men, outstanding military men, philosophers and economists, prominent thinkers, the coup attempt became an exam: some showed strengths, some showed weaknesses, some showed determination, courage, self-sacrifice, while others began to hesitate and could not maintain the sequence of actions, retreated.

The historical significance of the Decembrist uprising is that they laid the foundations of revolutionary traditions. Their speech marked the beginning of the further development of liberation thoughts in serf Russia.

...Finally, the fateful December 14th arrived - a remarkable number: it was minted on the medals with which deputies of the People's Assembly were dissolved to draw up laws in 1767 under Catherine II.

It was a gloomy December St. Petersburg morning, with 8° below zero. Before nine o'clock the entire governing Senate was already in the palace. Here and in all guard regiments the oath was taken. Messengers constantly galloped to the palace with reports of how things were going. Everything seemed quiet. Some mysterious faces appeared on Senate Square in noticeable anxiety. One, who knew about the order of the society and was passing through the square opposite the Senate, was met by the publisher of “Son of the Fatherland” and “Northern Bee”, Mr. Grech. To the question: “Well, will anything happen?” he added the phrase of the notorious Carbonari. The circumstance is not important, but it characterizes table demagogues; he and Bulgarin became zealous slanderers of the dead because they were not compromised.

Shortly after this meeting, at about 10 o’clock on Gorokhov Prospekt, drumming and the often repeated “Hurray!” were suddenly heard. A column of the Moscow Regiment with a banner, led by Staff Captain Shchepin-Rostovsky and two Bestuzhevs, entered Admiralty Square and turned towards the Senate, where it formed a square. Soon it was quickly joined by the Guards crew, carried away by Arbuzov, and then by a battalion of life grenadiers, brought by adjutant Panov (Panov convinced the life grenadiers, after already taking the oath, to follow him, telling them that “ours” do not take the oath and occupied the palace. He really led them to the palace, but, seeing that the life rangers were already in the yard, he joined the Muscovites) and Lieutenant Sutgof. Many ordinary people came running and immediately dismantled the woodpile of firewood that stood at the dam surrounding the buildings of St. Isaac's Cathedral. Admiralty Boulevard was filled with spectators. It immediately became known that this entry into the square was marked by bloodshed. Prince Shchepin-Rostovsky, beloved in the Moscow regiment, although he did not clearly belong to society, but was dissatisfied and knew that an uprising was being prepared against Grand Duke Nicholas, managed to convince the soldiers that they were being deceived, that they were obliged to defend the oath taken to Constantine, and therefore must go to the Senate.

Generals Shenshin and Fredericks and Colonel Khvoshchinsky wanted to reassure them and stop them. He cut down the first and wounded one non-commissioned officer and one grenadier, who wanted to prevent the banner from being given and thereby entice the soldiers. Luckily, they survived.

Count Miloradovich, unharmed in so many battles, soon fell as the first victim. The insurgents barely had time to line up in a square when [he] appeared galloping from the palace in a pair of sleighs, standing, wearing only a uniform and a blue ribbon. You could hear from the boulevard how he, holding the coachman’s shoulder with his left hand and pointing with his right, ordered him: “Go around the church and turn right to the barracks.” Less than three minutes later, he returned on horseback in front of the square (He took the first horse, which stood saddled at the apartment of one of the Horse Guards officers) and began to convince the soldiers to obey and swear allegiance to the new emperor.

Suddenly a shot rang out, the count began to shake, his hat flew off, he fell to the bow, and in this position the horse carried him to the apartment of the officer to whom it belonged. Exhorting the soldiers with the arrogance of an old father-commander, the count said that he himself willingly wished for Constantine to be emperor. One could believe that the count spoke sincerely. He was excessively wasteful and always in debt, despite frequent monetary rewards from the sovereign, and Constantine's generosity was known to everyone. The Count could have expected that with him he would live even more extravagantly, but what to do if he refused; assured them that he himself had seen the new renunciation, and persuaded them to believe him.

One of the members of the secret society, Prince Obolensky, seeing that such a speech could have an effect, leaving the square, convinced the count to drive away, otherwise he threatened with danger. Noticing that the count was not paying attention to him, he inflicted a light wound on his side with a bayonet. At this time, the count made a volt-face, and Kakhovsky fired a fatal bullet at him from a pistol, which had been poured the day before (the count’s saying was known to the entire army: “My God! the bullet was not poured on me!” - which he always repeated when they warned against dangers in battles or were surprised in salons that he was never wounded.). When he was taken off his horse at the barracks and carried into the officer’s apartment mentioned above, he had the last consolation of reading a handwritten note from his new sovereign expressing regret - and at 4 o’clock in the afternoon he no longer existed.

Here the importance of the uprising was fully expressed, by which the feet of the insurgents, so to speak, were chained to the place they occupied. Not having the strength to go forward, they saw that there was no salvation going back. The die was cast. The dictator did not appear to them. There was disagreement in the punishment. There was only one thing left to do: stand, defend and wait for the outcome from fate. They did it.

Meanwhile, according to the orders of the new emperor, columns of loyal troops instantly gathered at the palace. The Emperor, regardless of the empress's assurances or the representations of zealous warnings, came out himself, holding the 7-year-old heir to the throne in his arms, and entrusted him to the protection of the Preobrazhensky soldiers. This scene produced the full effect: delight in the troops and pleasant, promising amazement in the capital. The Emperor then mounted a white horse and rode out in front of the first platoon, moving the columns from the Exertsirhaus to the boulevard. His majestic, although somewhat gloomy, calmness then attracted everyone's attention. At this time, the insurgents were momentarily flattered by the approach of the Finnish regiment, whose sympathy they still trusted. This regiment walked along the St. Isaac's Bridge. He was led to the others who had sworn allegiance, but the commander of the 1st platoon, Baron Rosen, came halfway across the bridge and ordered to stop! The entire regiment stopped, and nothing could move it until the end of the drama. Only the part that did not climb the bridge crossed the ice to the Promenade des Anglais and then joined the troops that had bypassed the insurgents from the Kryukov Canal.

Soon, after the sovereign left for Admiralty Square, a stately dragoon officer approached him with military respect, whose forehead was tied with a black scarf under his hat (This was Yakubovich, who came from the Caucasus, had the gift of speech and knew how to interest the St. Petersburg people with stories about his heroic exploits salons. He did not hide his displeasure and personal hatred towards the late sovereign among the liberals, and during the 17-day period, members of the secret society were convinced that if possible, “he would show himself.”), and after a few words he went to the salons. square, but soon returned empty-handed. He volunteered to persuade the rebels and received one insulting reproach. Immediately, by order of the sovereign, he was arrested and suffered the common fate of those convicted. After him, General Voinov drove up to the insurgents, at whom Wilhelm Kuchelbecker, poet, publisher of the magazine “Mnemosyne”, who was then in punishment, fired a pistol shot and thereby forced him to leave. Colonel Sturler came to the life grenadiers, and the same Kakhovsky wounded him with a pistol. Finally, Grand Duke Mikhail himself arrived - and also without success. They answered him that they finally wanted the reign of laws. And with this, the pistol raised at him by the same Kuchelbecker’s hand forced him to leave. The pistol was already loaded. After this failure, Seraphim, the Metropolitan, in full vestments, with a cross presented with banners, emerged from the St. Isaac's Church temporarily built in the Admiralty buildings. Approaching the square, he began his exhortation. Another Kuchelbecker, the brother of the one who forced Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich to leave, came out to him. A sailor and a Lutheran, he did not know the high titles of our Orthodox humility and therefore said simply, but with conviction: “Go away, father, it is not your business to interfere in this matter.” The Metropolitan turned his procession to the Admiralty. Speransky, looking at this from the palace, said to Chief Prosecutor Krasnokutsky, who was standing with him: “And this thing failed!” Krasnokutsky himself was a member of a secret society and later died in exile (above his ashes there is a marble monument with a modest inscription: “Sister to a suffering brother.” He is buried in the Tobolsk cemetery near the church). This circumstance, no matter how insignificant, nevertheless reveals Speransky’s disposition of mind at that time. It could not be otherwise: on the one hand, the memory of what has been suffered is innocent, on the other hand, there is distrust of the future.

When the whole process of taming by peaceful means was thus completed, the action of arms began. General Orlov, with complete fearlessness, twice launched an attack with his horse guards, but the peloton fire overturned the attacks. Without defeating the square, he, however, thereby conquered an entire fictitious county.

The Emperor, slowly moving his columns, was already closer to the middle of the Admiralty. On the north-eastern corner of Admiralteysky Boulevard, an ultima ratio [last argument] appeared - guns of the Guards artillery. Their commander, General [al] Sukhozanet, drove up to the square and shouted to put down the guns, otherwise he would shoot with buckshot. They aimed a gun at him, but a contemptuously commanding voice was heard from the square: “Don’t touch this..., he’s not worth a bullet” (These words were shown later during interrogations in the committee, with the members of which Sukhozanet already shared the honor of wearing general[er] -Adjutant aiguillette. This is not enough, he was later the chief director of the cadet corps and the president of the Military Academy. However, we must be fair: he lost his leg in the Polish campaign.). This, naturally, offended him to the extreme. Jumping back to the battery, he ordered a volley of blank charges to be fired: it had no effect! Then the grapeshots whistled; here everything trembled and scattered in different directions, except for the fallen. This could have been enough, but Sukhozanet fired a few more shots along the narrow Galerny Lane and across the Neva towards the Academy of Arts, where more of the crowd of curious people fled! So this accession to the throne was stained with blood. In the outskirts of Alexander's reign, impunity for the heinous crime committed and merciless punishment for the forced noble uprising - open and with complete selflessness - became eternal terms.

The troops were disbanded. St. Isaac's and Petrovskaya squares are furnished with cadets. Many lights were laid out, by the light of which the wounded and dead were removed all night and the spilled blood was washed from the square. But stains of this kind cannot be removed from the pages of inexorable history. Everything was done in secret, and the true number of those killed and wounded remained unknown. Rumor, as usual, arrogated the right to exaggeration. Bodies were thrown into ice holes; claimed that many were drowned half-dead. Many arrests were made that same evening. From the first taken: Ryleev, book. Obolensky and two Bestuzhevs. They are all imprisoned in the fortress. In the following days, most of those arrested were brought to the palace, some even with their hands tied, and personally presented to the emperor, which gave rise to Nikolai Bestuzhev (He first managed to hide and escape to Kronstadt, where he lived for some time at the Tolbukhin lighthouse among the sailors loyal to him ) later tell one of the adjutant generals on duty that they had made a move out of the palace.

NICHOLAS I - KONSTANTIN PAVLOVICH

<...>I am writing you a few lines just to tell you good news from here. After the terrible 14th we were fortunately back to normal; there remains only some anxiety among the people, which, I hope, will dissipate as calm is established, which will be obvious evidence of the absence of any danger. Our arrests are very successful, and we have all the main characters of this day in our hands, except one. I have appointed a special commission to investigate the matter<...>Subsequently, for the sake of the court, I propose to separate those who acted consciously and premeditatedly from those who acted as if in a fit of madness<...>

KONSTANTIN PAVLOVICH - NICHOLAS I

<...>Great God, what events! This bastard was unhappy that he had an angel as his sovereign, and conspired against him! What do they need? This is monstrous, terrible, covers everyone, even if they are completely innocent, who did not even think about what happened!..

General Dibich told me all the papers, and one of them, which I received the day before, is more terrible than all the others: this is the one in which Volkonsky called for a change of government. And this conspiracy has been going on for 10 years! How did it happen that he was not discovered immediately or for a long time?

ERRORS AND CRIMES OF OUR CENTURY

Historian N.M. Karamzin was a supporter of enlightened autocracy. In his opinion, this is a historically natural form of government for Russia. It is no coincidence that he characterized the reign of Ivan the Terrible with these words: “The life of a tyrant is a disaster for humanity, but his history is always useful for sovereigns and peoples: to instill disgust for evil is to instill love for virtue - and the glory of the time when a writer armed with the truth can, in autocratic rule, put such a ruler to shame, so that there will be no more like him in the future! The graves are emotionless; but the living fear eternal damnation in History, which, without correcting evildoers, sometimes prevents atrocities, which are always possible, for wild passions rage even in the centuries of civil education, leading the mind to remain silent or to justify its frenzy with a slavish voice.”

Such views could not be accepted by opponents of autocracy and slavery - members of the secret societies that existed at that time, later called the Decembrists. Moreover, Karamzin was closely acquainted with many of the leaders of the movement and lived in their houses for a long time. Karamzin himself bitterly noted: “Many of the members [of the secret society] honored me with their hatred or, at least, did not love me; and I, it seems, am not an enemy of either the fatherland or humanity.” And assessing the events of December 14, 1825, he said: “The errors and crimes of these young people are the errors and crimes of our century.”

DECEMBRIST IN EVERYDAY LIFE

Was there a special everyday behavior of the Decembrist that distinguished him not only from reactionaries and “extinguishers”, but also from the mass of liberal and educated nobles of his time? Studying the materials of the era allows us to answer this question positively. We ourselves feel this with the direct instinct of the cultural successors of previous historical development. So, without even going into reading the comments, we feel Chatsky as a Decembrist. However, Chatsky is not shown to us at a meeting of the “most secret union” - we see him in his everyday surroundings, in a Moscow manor house. Several phrases in Chatsky’s monologues characterizing him as an enemy of slavery and ignorance are, of course, essential for our interpretation, but his manner of holding himself and speaking is no less important. It is precisely from Chatsky’s behavior in the Famusovs’ house, from his refusal of a certain type of everyday behavior:

The patrons yawn at the ceiling,

Show up to be quiet, shuffle around, have lunch,

Bring a chair, hand a handkerchief...

He is unmistakably defined by Famusov as a “dangerous person.” Numerous documents reflect various aspects of the everyday behavior of the noble revolutionary and allow us to speak of the Decembrist not only as the bearer of one or another political program, but also as a certain cultural, historical and psychological type.

At the same time, we should not forget that each person in his behavior implements not just one program of action, but constantly makes a choice, updating any one strategy from an extensive set of possibilities. Each individual Decembrist in his real everyday behavior did not always behave like a Decembrist - he could act like a nobleman, an officer (already: a guardsman, a hussar, a staff theorist), an aristocrat, a man, a Russian, a European, a young man, etc., etc. . However, in this complex set of possibilities there was also some special behavior, a special type of speech, action and reaction, inherent specifically to a member of a secret society. The nature of this special behavior will be of immediate interest to us...

Of course, each of the Decembrists was a living person and, in a certain sense, behaved in a unique way: Ryleev in everyday life is not like Pestel, Orlov is not like N. Turgenev or Chaadaev. Such a consideration, however, cannot be a basis for doubting the legitimacy of our task. After all, the fact that people’s behavior is individual does not negate the legitimacy of studying such problems as “the psychology of a teenager” (or any other age), “the psychology of women” (or men) and - ultimately - “human psychology”. It is necessary to supplement the view of history as a field for the manifestation of various social, general historical patterns by considering history as the result of human activity. Without studying the historical and psychological mechanisms of human actions, we will inevitably remain at the mercy of very schematic ideas. In addition, the fact that historical patterns realize themselves not directly, but through human psychological mechanisms, is in itself the most important mechanism of history, since it saves it from the fatal predictability of processes, without which the entire historical process would be completely redundant.

PUSHKIN AND THE DECEMBRISTS

The years 1825 and 1826 were a milestone, a boundary that divided many biographies into periods before and after...

This applies, of course, not only to members of secret societies and participants in the uprising.

A certain era, people, style was fading into the past. The average age of those convicted by the Supreme Criminal Court in July 1826 was twenty-seven years: the “average year of birth” of a Decembrist was 1799. (Ryleev - 1795, Bestuzhev-Ryumin - 1801, Pushchin - 1798, Gorbachevsky - 1800...). Pushkin's age.

“A time of hope,” Chaadaev will remember about the pre-Decembrist years.

“Lyceum students, Yermolovites, poets,” - Kuchelbecker will define an entire generation. The noble generation, which reached the height of enlightenment from which it was possible to see and hate slavery. Several thousand young people, witnesses and participants in such world events, which would be enough, it seems, for several ancient, grandfather’s and great-grandfather’s centuries...

What, what have we witnessed...

People often wonder where great Russian literature suddenly, “immediately” came from? Almost all of its classics, as the writer Sergei Zalygin noted, could have had one mother; the firstborn - Pushkin was born in 1799, the youngest - Leo Tolstoy in 1828 (and between them Tyutchev - 1803, Gogol - 1809, Belinsky - 1811, Herzen and Goncharov - 1812, Lermontov - 1814, Turgenev - 1818, Dostoevsky, Nekrasov - 1821, Shchedrin - 1826)...

Before there were great writers, and at the same time with them, there had to be a great reader.

The youth who fought on the fields of Russia and Europe, lyceum students, southern freethinkers, publishers of the "Polar Star" and other companions of the main character of the book - the first revolutionaries, with their writings, letters, actions, words, testify in various ways to the special climate of the 1800-1820s, which was created by them together, in which a genius could and should grow in order to further ennoble this climate with his breath.

Without the Decembrists there would have been no Pushkin. By saying this, we obviously mean a huge mutual influence.

Common ideals, common enemies, common Decembrist-Pushkin history, culture, literature, social thought: that is why it is so difficult to study them separately, and there is so little work (we hope for the future!), where that world will be considered as a whole, as diverse, living , ardent unity.

Born from the same historical soil, two such unique phenomena as Pushkin and the Decembrists could not, however, merge and dissolve in each other. Attraction and at the same time repulsion is, firstly, a sign of kinship: only proximity and commonality give rise to some important conflicts and contradictions, which cannot exist at a great distance. Secondly, this is a sign of maturity and independence.

Drawing on new materials and reflecting on well-known materials about Pushkin and Pushchin, Ryleev, Bestuzhev, Gorbachevsky, the author tried to show the union of those arguing, those who disagree in agreement, those who agree in disagreement...

Pushkin, with his brilliant talent and poetic intuition, “grinds” and masters the past and present of Russia, Europe, and humanity.

And I heard the sky tremble

And the heavenly flight of angels...

A poet-thinker not only of Russian, but also of world-historical rank - in some significant respects, Pushkin penetrated deeper, wider, and further than the Decembrists. We can say that he moved from an enthusiastic attitude towards revolutionary upheavals to an inspired insight into the meaning of history.

The power of protest - and social inertia; “the cry of honor” - and the dream of “peaceful peoples”; the doom of the heroic impulse - and other, “Pushkin”, paths of historical movement: all this arises, is present, lives in “Some Historical Remarks” and the works of the first Mikhailovsky Autumn, in interviews with Pushchin and in “Andrei Chenier”, in letters of 1825, "To the Prophet." There we find the most important human and historical revelations, Pushkin’s command addressed to himself:

And see and listen...

The courage and greatness of Pushkin lies not only in his rejection of autocracy and serfdom, not only in his loyalty to his dead and imprisoned friends, but also in the courage of his thought. It is customary to talk about Pushkin’s “limitedness” in relation to the Decembrists. Yes, by determination and confidence to go into open rebellion, sacrificing themselves, the Decembrists were ahead of all their compatriots. The first revolutionaries set a great task, sacrificed themselves and remained forever in the history of the Russian liberation movement. However, on his way, Pushkin saw, felt, understood more... He, before the Decembrists, seemed to experience what they were later to experience: albeit in the imagination, but that’s why he’s a poet, that’s why he’s a brilliant artist-thinker of Shakespeare’s , Homeric scale, who once had the right to say: “The history of the people belongs to the Poet.”

The cavalry guard's life is short-lived,

And that's why he's so sweet.

The trumpet is blowing, the curtains are thrown back,

And somewhere you can hear the sound of sabers... (B. Okudzhava)

As you know, the Decembrists took advantage of the interregnum situation for their speech: Emperor Alexander I died without leaving an heir. The throne was supposed to pass to his younger brother Constantine, but he had long ago renounced the succession to the throne, but almost no one knew about this. In this situation, the next oldest brother, Nikolai, should have taken power, but he did not dare to do this, because... many had already sworn allegiance to Constantine, and in the eyes of the people Nicholas would have looked like an impostor, especially since he was not particularly popular. While Nicholas was negotiating with Konstantin, who did not confirm his abdication and did not accept power, the Decembrists decided to start a speech.

Uprising plan

Of course, members of secret societies had it. They had been preparing for the uprising for about 10 years, carefully thinking through all the options and gathering forces, but they did not have a specific date for their performance. They decided to use the ensuing situation of interregnum to realize their plan: “...now, after the death of the sovereign, there is the most convenient time to put into action the previous intention.” However, the heated discussions that began about the situation, which took place mainly in K. Ryleev’s apartment, did not immediately lead to coordinated actions - there were disputes and differences of opinion. Finally, a somewhat unanimous opinion emerged, supported by the majority. They also came to the decision that the uprising should be led by a dictator, who was appointed S. Trubetskoy.

The main goal of the uprising was the crushing of the autocratic serfdom, the introduction of representative government, i.e. adoption of the constitution. An important point of the plan was the convening of the Great Council (it was supposed to meet in the event of a coup). The cathedral was supposed to replace the outdated autocratic serf system of Russia with a new, representative system. This was the maximum program. But there was also a minimum program: before the convening of the Great Council, act in accordance with the manifesto drawn up, gain supporters and after that identify issues and problems for discussion at this council.

This manifesto was written down by S. Trubetskoy, in any case, it was found in his papers during the search, it appeared in his investigative file.

Manifesto

- Destruction of the former government.

- The institution is temporary until a permanent one is established.

- Free embossing, and therefore the elimination of censorship.

- Free worship of all faiths.

- Destruction of property rights extending to people.

- Equality of all classes before the law, and therefore the abolition of military courts and all kinds of judicial commissions, from which all judicial cases are transferred to the departments of the nearest civil courts.

- Declaration of the right of every citizen to do whatever he wants, and therefore a nobleman, merchant, tradesman, peasant still have the right to enter into military and civil service and into the clergy, trade wholesale and retail, paying the established duties for trading. Acquire all kinds of property, such as: lands, houses in villages and cities; enter into all kinds of conditions among themselves, compete with each other before the court.

- Addition of poll taxes and arrears on them.

- Elimination of monopolies, such as: on salt, on the sale of hot wine, etc. and therefore the establishment of free distillation and salt extraction, with payment for. industry from the production of salt and vodka.

10.Destruction of recruitment and military settlements.

11. Reducing the length of military service for lower ranks, and determining it will follow the equation of military service between all classes.

12. Resignation of all lower ranks, without exception, who have served for 15 years.

13. The establishment of volost, district, provincial and regional boards, and the procedure for electing members of these boards, which should replace all officials hitherto appointed from the civil government.

14.Publicity of courts.

15.Introduction of juries into criminal and civil courts.

Establishes a board of 2 or 3 persons, to which all parts of the top management, that is, all ministries, are subordinated. Council, Committee of Ministers, army, navy. In a word, the entire supreme, executive power, but by no means legislative or judicial. - For this latter, there remains a ministry subordinate to the temporary government, but for the judgment of cases not resolved in the lower instances, the criminal department of the Senate remains and a civil department is established, which are finally decided , and whose members will remain until a permanent government is established.

The temporary board is entrusted with the enforcement of:

- Equal rights of all classes.

- Formation of local volost, district, provincial and regional boards.

- Formation of the internal people's guard,

- Formation of a trial with a jury.

- Equation of conscription between classes.

- Destruction of the standing army.

- The establishment of a procedure for electing elected representatives to the House of People's Representatives, who must approve for the future the existing order of government and state legislation.

It was supposed to publish the Manifesto to the Russian people on the day of the uprising - December 14, 1825. The troops were supposed to remain on Senate Square until negotiations were ongoing with the Senate, to convince the Senate (if the Senate disagreed, the use of military force was allowed) to accept the Manifesto, and disseminate it. Then the troops had to withdraw from the city center to protect St. Petersburg from possible actions by government troops.

Thus, according to the plan, on the morning of December 14, the rebel regiments were to gather on Senate Square and force the Senate to issue a Manifesto. Guardsmen - capture the Winter Palace and arrest the royal family, and then occupy the Peter and Paul Fortress. The Constituent Assembly was supposed to establish the form of government in the country and determine the fate of the king and his family.

In case of failure, the troops had to leave St. Petersburg and reach the Novgorod military settlements, where they would meet support.

Senate Square December 14, 1825

But already early in the morning the well-thought-out plan began to crumble. K. Ryleev insists on the murder of the tsar, which was not included in the immediate plans, due to the interregnum. The murder of the tsar was entrusted to P. Kakhovsky, it was supposed to mark the beginning of the uprising. But Kakhovsky refuses to commit murder. In addition, Yakubovich, appointed to command the guards during the capture of the Winter Palace, also refused to carry out this task. In addition to everything, Mikhail Pushchin refused to bring a cavalry squadron to the square. We had to hastily rebuild the plan: Nikolai Bestuzhev was appointed instead of Yakubovich.

At 11 o'clock in the morning, the Moscow Life Guards Regiment was the first to arrive on Senate Square and was lined up in the shape of a square near the monument to Peter. People began to gather. At this time, St. Petersburg Governor General Miloradovich arrived on the square. He persuaded the soldiers to disperse, convinced them that the oath to Nicholas was legal. It was a tense moment of the uprising, events could have gone according to an unforeseen scenario, because the regiment was alone, the others had not yet arrived, and Miloradovich, the hero of 1812, was popular among the soldiers and knew how to talk to them. The only solution was to remove Miloradovich from the square. The Decembrists demanded that he leave the square, but Miloradovich continued to persuade the soldiers. Then Obolensky turned his horse with a bayonet, wounding the governor-general, and Kakhovsky fired and inflicted a mortal wound on him.

Ryleev and I. Pushchin at this time went to Trubetskoy; on the way they learned that the Senate had already sworn allegiance to the Tsar and dispersed, i.e. the troops had already gathered in front of the empty Senate. But Trubetskoy was not there, nor was he on Senate Square. The situation in the square required decisive action, but the dictator did not appear. The troops continued to wait. This delay played a decisive role in the defeat of the uprising.

The people in the square clearly supported the rebels, but they did not take advantage of this support, obviously fearing the activity of the people, a “senseless and merciless” riot, according to Pushkin. Contemporaries of the events unanimously note in their memoirs that tens of thousands of people who sympathized with the rebels gathered in the square. Later, Nikolai told his brother several times: “The most amazing thing in this story is that you and I weren’t shot then.”

Meanwhile, government troops, on the orders of Emperor Nicholas, were drawn to Senate Square; cavalry troops began to attack the Moscow regiment stationed in a square, but were repulsed. Then Nicholas called on Metropolitan Seraphim for help in order to explain to the soldiers the legality of the oath to him, and not to Constantine.

But the Metropolitan’s negotiations were fruitless, and troops supporting the uprising continued to gather in the square: the Life Guards of the Grenadiers, the naval crew. Thus, on Senate Square there were:

- Moscow regiment led by brothers A. and M. Bestuzhev.

- The first detachment of life grenadiers (Sutgof company).

- Guards naval crew under the command of Captain-Lieutenant Nikolai Bestuzhev (elder brother of Alexander and Mikhail) and Lieutenant Arbuzov.

- The rest, the most significant part, is the life grenadier under the command of Lieutenant Panov.

V. Masutov "Nicholas I in front of the formation of the Life Guards Sapper Battalion in the courtyard of the Winter Palace on December 14, 1825"

Due to the continued absence of the dictator S. Trubetskoy, already in the middle of the day the Decembrists elected a new dictator - Prince Obolensky, who was the chief of staff of the uprising. And at that time Trubetskoy was sitting in the office of the General Staff and periodically looked around the corner, watching what was happening on Senate Square. He simply chickened out at the last moment, and his comrades waited, thinking that his delay was due to some unforeseen circumstances.

But by this time government troops had already surrounded the rebels. At three o'clock in the afternoon it was already getting dark, soldiers from the imperial troops began to run over to the rebels. And then Nikolai gave the order to shoot with buckshot. But the first shot was delayed: the soldiers did not want to shoot at their own, and then the officer did it. The rebels had no artillery; they responded with rifle shots. After the second shot, the square trembled, the soldiers rushed onto the thin ice of the Neva - the ice split from the falling cannonballs, many drowned...

The uprising was suppressed.

Late in the evening, some of the Decembrists gathered at Ryleev’s apartment. They understood that arrests awaited them, so they agreed on how to behave during interrogations, said goodbye to each other, worried about how to inform Southern society that the case was lost... that Trubetskoy and Yakubovich had changed...

In total, on December 14, 1825, government troops killed 1,271 people, of which 9 were women and 19 children, 903 were “mobs,” the rest were military.

On December 14, officers who were members of the secret society were still in the barracks after dark and campaigned among the soldiers.

Alexander Bestuzhev gave a hot speech to the soldiers of the Moscow Regiment. “I spoke strongly, they listened to me eagerly,” he later recalled. From the oath but-

The soldiers refused the king and decided to go to Senate Square. The regimental commander of the Moscow regiment, Baron Fredericks, wanted to prevent the rebel soldiers from leaving the barracks - and fell with a severed head under the blow of the saber of officer Shchepin-Rostovsky. Colonel Khvoshchinsky, who wanted to stop the soldiers, was also wounded. With the regimental banner flying, taking live ammunition and loading their guns, the soldiers of the Moscow Regiment were the first to come to Senate Square. At the head of these first revolutionary troops in the history of Russia was the staff captain of the Life Guards Dragoon Regiment, Alexander Bestuzhev. Along with him at the head of the regiment were his brother, staff captain of the Life Guards of the Moscow Regiment, Mikhail Bestuzhev, and staff captain of the same regiment, Dmitry Shchepin-Rostovsky.

The regiment lined up in battle formation in the form of a square near the monument to Peter 1. The square (battle quadrangle) was a proven and proven combat formation, providing both defense and attack on the enemy from four sides. It was two o'clock in the morning. The St. Petersburg governor-general Miloradovich galloped up to the rebels, began to persuade the soldiers to disperse, swore that the oath to Nicholas was correct, took out the sword given to him by Tsarevich Konstantin with the inscription: “To my friend Miloradovich,” reminded of the battles of 1812. The moment was very dangerous: The regiment was still alone, other regiments had not yet arrived; the hero of 1812, Miloradovich, was widely popular and knew how to talk to the soldiers. The uprising that had just begun was in great danger. Miloradovich could greatly sway the soldiers and achieve success. It was necessary to interrupt his campaigning at all costs and remove him from the square. But, despite the demands of the Decembrists, Miloradovich did not leave and continued persuasion. Then the chief of staff of the rebels, Decembrist Obolensky, turned his horse with a bayonet, wounding the count in the thigh, and a bullet, fired at the same moment by Kakhovsky, mortally wounded the general. The danger looming over the uprising was repelled.

The delegation chosen to address the Senate - Ryleev and Pushchin - went to Trubetskoy early in the morning, who had previously visited Ryleev himself. It turned out that the Senate had already sworn in and the senators had left. It turned out that the rebel troops had gathered in front of

Diagram of the deployment of troops on Senate Square on December 14, 1825 (according to G. S. Gabaev)

The rebels(about 3,000 infantry):

Kore A. Bestuzhev- L.-Guards. Moscow regiment (671 people).

1. Front M. Bestuzheva(2 1/2 companies);

2. Face book. Shchepina (2 companies);

3. Book chain. V. Obolensky (about 40 people);

L-Guards. Grenada. p.(about 1,250 people);

4. Fas Sutgof (1 company);

5. Fasy Panov (1 battalion - 4 companies).

Column of N. Bestuzhev- Guard. crew - about 1100 people.

6. 1 baht. (8 companies and art. team).

Neutral(about 500 infantry):

7. L.-Gv, Finland. n. bar. Rosen (2 1/2, companies).

Government troops(infantry - about 9,000 people, cavalry - about 3,000 people and artillery - 36 guns):

8. L.-Guards. Preobrazh. regiment 1 company;

9. L.-Guards. Finland. regiment 1 1/2 companies;

10. L.-Gv. Horse regiment (2 units):

11. L.-Guards. 1st Equestrian peony. 1 3/4 Esq.;

12. L.-Guards. Finland. village guard (about 25 people);

13. L.-Guards. Pavlovsk. n. baht (3 companies);

14. 1st Konio-Pioneer 1/4 Esq.;

15. Cavalier. p. 1/4 veins;

16. Leningrad Guards, Semenovsk. item 2 baht. (8 mouths);

17. L.-Guards. Grenada. St. company (137 people);

18. L.-Guards. Equestrian p., 5 esq.;

19. L.-Guards. Preobrazh. p. (1 3/4 baht. - 7 mouth);

20. L.-Guards. Moscow St. baht (641 people);

21. L.-Gv. Izmailovsk. item 2 baht. (8 mouths);

22. L.-Guards. Yegersk. item 2 baht.;

23. Cavalier. item 6 3/4, esc;

24. L.-Guards. 1 art. brig. 2 2/3 companies - 32 guns.

empty Senate. Thus, the first goal of the uprising was not achieved. It was a bad failure. Another planned link was breaking away from the plan. Now the Winter Palace and the Peter and Paul Fortress were to be captured.

What exactly Ryleev and Pushchin talked about at this last meeting with Trubetskoy is unknown, but, obviously, they agreed on some new plan of action and, when they then came to the square, they brought with them the confidence that Trubetskoy would now come there, to area, and will take command. Everyone was waiting impatiently for Trubetskoy.

But there was still no dictator. Trubetskoy betrayed the uprising. A situation was developing in the square that required decisive action, but Trubetskoy did not dare to take it. He sat, tormented, in the office of the General Staff, went out, looked around the corner to see how many troops had gathered in the square, and hid again. Ryleev looked for him everywhere, but could not find him. Who could have guessed that the dictator of the uprising was sitting on the tsarist General Staff? Members of the secret society, who elected Trubetskoy as dictator and trusted him, could not understand the reasons for his absence and thought that he was being delayed by some reasons important for the uprising. Trubetskoy’s fragile noble revolutionary spirit easily broke when the hour of decisive action came.

A leader who betrayed the cause of the revolution at the most decisive moment, of course, is to some extent (but only to some extent!) an exponent of the class limitations of noble revolutionism. But still, the failure of the elected dictator to appear on the square to meet the troops during the hours of the uprising is an unprecedented case in the history of the revolutionary movement. The dictator thereby betrayed the idea of uprising, his comrades in the secret society, and the troops who followed them. This failure to appear played a significant role in the defeat of the uprising.

The rebels waited for a long time. The soldiers' guns fired on their own. Several attacks launched on the orders of Nicholas by the horse guards on the square of the rebels were repulsed by rapid rifle fire. The barrage chain, separated from the square of the rebels, disarmed the tsarist police. The “rabble” who were in the square were doing the same thing (the broadsword of one disarmed gendarme was

handed over to A.S. Pushkin’s brother Lev Sergeevich, who came to the square and joined the rebels).

Behind the fence of St. Isaac's Cathedral, which was under construction, were the dwellings of construction workers, for whom a lot of firewood was prepared for the winter. The village was popularly called “Isaac’s village,” and from there a lot of stones and logs flew at the king and his retinue 1).

We see that the troops were not the only living force in the uprising on December 14: on Senate Square that day there was another participant in the events - huge crowds of people.

The words of Herzen are well known: “The Decembrists on Senate Square did not have enough people.” These words must be understood not in the sense that there were no people in the square at all, there were people, but in the fact that the Decembrists were unable to rely on the people, to make them an active force of the uprising.

Throughout the interregnum, the streets of St. Petersburg were busier than usual. This was especially noticeable on Sunday, December 13, when rumors spread about a new oath, a new emperor and the abdication of Constantine. On the day of the uprising, while it was still dark, people began to gather here and there at the gates of the barracks of the guard regiments, attracted by rumors about the upcoming oath, and perhaps by widespread rumors about some benefits and relief for the people that would now be announced at the oath. These rumors undoubtedly came from the direct agitation of the Decembrists. Shortly before the uprising, Nikolai Bestuzhev and his comrades went around the military guards at the barracks at night and told the sentries that serfdom would soon be abolished and the length of military service would be reduced. The soldiers eagerly listened to the Decembrists.

A contemporary’s impression of how “empty” it was in other parts of St. Petersburg at that moment is curious: “The further I moved away from the Admiralty, the fewer people I met; it seemed that everyone had come running to the square, leaving their houses empty.” An eyewitness, whose last name remained unknown, said: “All of St. Petersburg flocked to the square, and the first Admiralty

part accommodated up to 150 thousand people, acquaintances and strangers, friends and enemies, forgot their identities and gathered in circles, talking about the subject that struck their eyes" 2)

It should be noted the amazing unanimity of the primary sources speaking about a huge crowd of people.

The “common people”, “black bones” prevailed - artisans, workers, artisans, peasants who came to the bars in the capital, men released on quitrent, “working people and commoners”, there were merchants, minor officials, students of high schools, cadet corps, apprentices... Two “rings” of people were formed. The first consisted of those who had arrived early, it was surrounded by a square of rebels. The second was formed from those who came later - the gendarmes were no longer allowed into the square to join the rebels, and the “late” people crowded behind the tsarist troops who surrounded the rebellious square. From these “later” arrivals a second ring was formed, surrounding government troops. Noticing this, Nikolai, as can be seen from his diary, realized the danger of this environment. It threatened with great complications.

The main mood of this huge mass, which, according to contemporaries, numbered in tens of thousands of people, was sympathy for the rebels.

Nikolai doubted his success, “seeing that the matter was becoming very important, and not yet foreseeing how it would end.” He ordered the preparation of carriages for members of the royal family with the intention of “showing them out” under the “cover of cavalry guards” to Tsarskoye Selo. Nicholas considered the Winter Palace an unreliable place and foresaw the possibility of a strong expansion of the uprising in the capital. The order to guard the palace to sappers spoke about the same thing: apparently, while guarding the Winter Tsar, he even imagined some hastily erected fortifications for batteries. Nicholas expressed these sentiments even more clearly, writing that in the event of bloodshed under the windows of the palace, “our fate would be more than doubtful.” And later Nikolai told his brother Mikhail many times: “The most surprising thing is

The important thing in this story is that you and I weren’t shot then.” There is little optimistic assessment of the general situation in these words. It must be admitted that in this case the historian must completely agree with Nikolai.

Under these conditions, Nicholas resorted to sending Metropolitan Seraphim and Kyiv Metropolitan Eugene to negotiate with the rebels. Both were already in the Winter Palace for a thanksgiving service on the occasion of the oath to Nicholas. But the prayer service had to be postponed: there was no time for a prayer service. The idea of sending metropolitans to negotiate with the rebels came to Nicholas’s mind as a way to explain the legality of the oath to him, and not to Constantine, through clergy who were authoritative in matters of the oath, “archpastors.” It seemed that who better to know about the correctness of the oath than the metropolitans? Nikolai’s decision to grasp at this straw was strengthened by alarming news: he was informed that life grenadiers and a guards naval crew were leaving the barracks to join the “rebels.” If the metropolitans had managed to persuade the rebels to disperse, then the new regiments that came to the aid of the rebels would have found the main core of the uprising broken and could have fizzled out themselves.

The sight of the approaching spiritual delegation was quite impressive. The patterned green and crimson velvet vestments against the background of white snow, the sparkling of diamonds and gold on panagias, high mitres and raised crosses, two accompanying deacons in magnificent, sparkling brocade surplices, worn for a solemn court service - all this should have attracted the attention of the soldiers .

But in response to the Metropolitan’s speech about the legality of the required oath and the horrors of shedding brotherly blood, the “rebellious” soldiers began shouting to him from the ranks, according to the authoritative testimony of Deacon Prokhor Ivanov: “What kind of metropolitan are you, when in two weeks you swore allegiance to two emperors... You are a traitor , are you a deserter, Nikolaev Kaluga? We don’t believe you, go away!.. This is none of your business: we know what we are doing...”

Suddenly the metropolitans rushed to the left, hid in a hole in the fence of St. Isaac's Cathedral, hired ordinary cab drivers (while on the right, closer to

Neva, they were released by the palace carriage) and returned to the Winter Palace on a detour. Why did this sudden flight of the clergy happen? Huge reinforcements were approaching the rebels. On the right, along the Neva, a detachment of rebel life grenadiers rose, fighting their way with weapons in their hands through the troops of the tsar's encirclement. On the other side, rows of sailors entered the square - the guards naval crew. This was the largest event in the uprising camp: its forces immediately more than quadrupled.

“The Guards crew, heading to Petrovskaya Square, was met by the Life Guards Moscow Regiment with exclamations of “Hurray!”, to which the Guards crew responded, which was repeated several times on the square,” says Mikhail Kuchelbecker.

Thus, the order of arrival of the rebel regiments to the square was as follows: the first to arrive was the Moscow Life Guards Regiment, led by the Decembrist Alexander Bestuzhev and his brother Mikhail Bestuzhev. Behind him (much later) was a detachment of life grenadiers - the 1st fusilier company of the Decembrist Sutgof, with its commander at its head; then the guards naval crew under the command of the Decembrist captain-lieutenant Nikolai Bestuzhev (the elder brother of Alexander and Mikhail) and the Decembrist lieutenant Arbuzov. Following the guards crew, the last participants in the uprising entered the square - the rest, the most significant part of the life grenadiers, brought by the Decembrist Lieutenant Panov. Sutgof's company joined the square, and the sailors lined up on the Galernaya side with another military formation - “a column to attack.” The life grenadiers who arrived later under the command of Panov formed a separate, third formation on Senate Square - the second “attack column”, located on the left flank of the rebels, closer to the Neva. About three thousand rebel soldiers gathered in the square with 30 Decembrist officers and combat commanders. All the rebel troops had weapons and live ammunition.

The rebels had no artillery. All the rebels were infantrymen.

An hour before the end of the uprising, the Decembrists elected a new “dictator” - Prince Obolensky, chief of staff of the uprising. He tried three times to convene a council of war,

but it was too late: Nicholas managed to take the initiative into his own hands and concentrate four times the military forces in the square against the rebels, and his troops included cavalry and artillery, which the Decembrists did not have at their disposal. Nicholas had 36 artillery pieces at his disposal. The rebels, as already mentioned, were surrounded by government troops on all sides.

The short winter day was approaching evening. “A piercing wind chilled the blood in the veins of the soldiers and officers who stood in the open for so long,” the Decembrists later recalled. The early St. Petersburg twilight was approaching. It was already 3 pm and it was getting noticeably dark. Nikolai was afraid of darkness. In the dark, the people gathered in the square would have been more active. From the ranks of the troops standing on the side of the emperor, runs began to run to the rebels. Delegates from some regiments that stood on Nicholas’s side were already making their way to the Decembrists and asking them to “hold out until the evening.” Most of all, Nikolai was afraid, as he later wrote in his diary, that “the excitement would not be communicated to the mob.” Nikolai gave the order to shoot with grapeshot. The command was given, but no shot was fired. The gunner who lit the fuse did not put it into the cannon. “Friends, your honor,” he quietly answered the officer who attacked him. Officer Bakunin snatched the fuse from the soldier’s hands and fired himself. The first volley of grapeshot was fired above the ranks of soldiers - precisely at the “mob” that dotted the roof of the Senate and neighboring houses. The rebels responded to the first volley of grapeshot with rifle fire, but then, under a hail of grapeshot, the ranks wavered and wavered - they began to flee, the wounded and dead fell. “In between shots, one could hear blood flowing along the pavement, melting the snow, then the alley itself froze,” the Decembrist Nikolai Bestuzhev later wrote. The Tsar's cannons fired at the crowd running along the Promenade des Anglais and Galernaya. Crowds of rebel soldiers rushed onto the Neva ice to move to Vasilyevsky Island. Mikhail Bestuzhev tried to form the soldiers into battle formation again on the ice of Nova and go on the offensive. The troops lined up. But the cannonballs hit the ice - the ice split, many drowned. Bestuzhev's attempt failed,

By nightfall it was all over. The tsar and his minions did their best to downplay the number of those killed - they talked about 80 corpses, sometimes about a hundred or two. But the number of victims was much more significant - buckshot at close range mowed down people. By order of the police, the blood was covered with clean snow and the dead were hastily removed. There were patrols everywhere. Bonfires were burning in the square, and the police sent people home with orders that all gates be locked. Petersburg looked like a city conquered by enemies.

The document of the Ministry of Justice official for the statistical department S. N. Korsakov, published by P. Ya. Cain, evokes the greatest confidence. There are eleven sections in the document. We learn from them that on December 14, “people were killed”: “1 generals, 1 staff officers, 17 chief officers of various regiments, 93 lower ranks of the Moscow Life Guards Regiment, 69 Grenadier Regiments, [ naval] crew of the Guard - 103, Horse - 17, in tailcoats and overcoats - 39, female - 9, minors - 19, mob - 903. The total number of killed is 1271 people” 3).

At this time, the Decembrists gathered at Ryleev’s apartment. This was their last meeting. They only agreed on how to behave during interrogations... The despair of the participants knew no bounds: the death of the uprising was obvious. Ryleev took the word from the Decembrist N.N. Orzhitsky that he would immediately go to Ukraine to warn Southern society that “Trubetskoy and Yakubovich have changed”

Notes:

1) According to the latest archival data obtained by G. S. Gabaev, the construction of St. Isaac's Cathedral occupied a larger area than shown on the schematic map (see, p. 110) and narrowed the field of action of the troops,

2) Teleshov I. Ya: December 14, 1825 in St. Petersburg. - Red Archive, 1925, v. 6 (13), p. 287; An eyewitness's story about December 14. - In the book: Collection of ancient papers stored in the P. I. Shchukin Museum, M„ 1899, part 5, p. 244.

Decembrist uprising

Prerequisites

The conspirators decided to take advantage of the complex legal situation that had developed around the rights to the throne after the death of Alexander I. On the one hand, there was a secret document confirming the long-standing renunciation of the throne by the brother next to the childless Alexander in seniority, Konstantin Pavlovich, which gave an advantage to the next brother, who was extremely unpopular among the highest military-bureaucratic elite to Nikolai Pavlovich. On the other hand, even before the opening of this document, Nikolai Pavlovich, under pressure from the Governor-General of St. Petersburg, Count M.A. Miloradovich, hastened to renounce his rights to the throne in favor of Konstantin Pavlovich.

On November 27, the population swore an oath to Constantine. Formally, a new emperor appeared in Russia; several coins with his image were even minted. But Constantine did not accept the throne, but also did not formally renounce it as emperor. An ambiguous and extremely tense interregnum situation was created. Nicholas decided to declare himself emperor. The second oath, the “re-oath,” was scheduled for December 14. The moment the Decembrists had been waiting for had arrived - a change of power. The members of the secret society decided to speak out, especially since the minister already had a lot of denunciations on his desk and arrests could soon begin.

The state of uncertainty lasted for a very long time. After the repeated refusal of Konstantin Pavlovich from the throne, the Senate, as a result of a long night meeting on December 13-14, 1825, recognized the legal rights to the throne of Nikolai Pavlovich.

The plans of the conspirators. Southern and Northern societies negotiated on coordination of actions and established contacts with the Polish Patriotic Society and the Society of United Slavs. The Decembrists planned to kill the Tsar at a military review, seize power with the help of the Guard and realize their goals. The performance was planned for the summer of 1826. However, on November 19, 1825, Alexander I suddenly died in Taganrog. The throne was supposed to pass to the deceased’s brother Konstantin, because Alexander had no children. But back in 1823, Constantine secretly abdicated the throne, which now, according to the law, passed to the next senior brother - Nicholas. Unaware of Constantine's abdication, the Senate, guard and army swore allegiance to him on November 27. After clarifying the situation, they re-sworn the oath to Nikolai, who, due to his personal qualities (pettiness, martinet, vindictiveness, etc.) was not liked in the guard. Under these conditions, the Decembrists had the opportunity to take advantage of the sudden death of the tsar, the fluctuations in power that found themselves in an interregnum, as well as the hostility of the guards towards the heir to the throne. It was also taken into account that some senior dignitaries took a wait-and-see attitude towards Nicholas and were ready to support active actions directed against him. In addition, it became known that the Winter Palace knew about the conspiracy and arrests of members of the secret society, which had actually ceased to be secret, could soon begin.

In the current situation, the Decembrists planned to raise the Guards regiments, gather them on Senate Square and force the Senate “with kindness” or at threat of arms to publish a “Manifesto to the Russian People,” which proclaimed the destruction of the autocracy, the abolition of serfdom, the establishment of a Provisional Government, political freedoms, etc. Some of the rebels were supposed to capture the Winter Palace and arrest the royal family, and it was planned to capture the Peter and Paul Fortress. In addition, P.G. Kakhovsky took upon himself the task of killing Nikolai before the start of the speech, but never decided to carry it out. Prince S.P. was elected leader of the uprising (“dictator”). Trubetskoy.

Uprising plan

The Decembrists decided to prevent the troops and the Senate from taking the oath to the new king. The rebel troops were supposed to occupy the Winter Palace and the Peter and Paul Fortress, the royal family was planned to be arrested and, under certain circumstances, killed. A dictator, Prince Sergei Trubetskoy, was elected to lead the uprising.

After this, it was planned to demand that the Senate publish a national manifesto, which would proclaim the “destruction of the former government” and the establishment of a Provisional Revolutionary Government. It was supposed to make Count Speransky and Admiral Mordvinov its members (later they became members of the trial of the Decembrists).

Deputies had to approve a new fundamental law - the constitution. If the Senate did not agree to publish the people's manifesto, it was decided to force it to do so. The manifesto contained several points: the establishment of a provisional revolutionary government, the abolition of serfdom, equality of all before the law, democratic freedoms (press, confession, labor), the introduction of jury trials, the introduction of compulsory military service for all classes, the election of officials, the abolition of the poll tax.

After this, a National Council (Constituent Assembly) was to be convened, which was supposed to decide on the form of government - a constitutional monarchy or a republic. In the second case, the royal family would have to be exiled abroad. In particular, Ryleev proposed exiling Nicholas to Fort Ross. However, then the plan of the “radicals” (Pestel and Ryleev) involved the murder of Nikolai Pavlovich and, possibly, Tsarevich Alexander. [source not specified 579 days]

Progress of the uprising. From the early morning of December 14, officers-members of the “Northern Society” campaigned among soldiers and sailors, convincing them not to swear allegiance to Nicholas, but to support Konstantin and “his wife “Constitution”.” They managed to bring part of the Moscow, Grenadier regiments and the Guards naval crew to Senate Square (about 3.5 thousand people in total). But by this time the senators had already sworn allegiance to Nicholas and dispersed. Trubetskoy, observing the implementation of all parts of the plan, saw that it was completely disrupted and, convinced of the doom of the military action, did not appear on the square. This in turn caused confusion and slowness of action.

Nicholas surrounded the square with troops loyal to him (12 thousand people, 4 guns). But the rebels repulsed the cavalry attacks, and Governor-General Miloradovich, who tried to persuade the rebels to surrender their weapons, was mortally wounded by Kakhovsky. After this, artillery was brought into action. The protest was suppressed, and in the evening mass arrests began.

Uprising in Ukraine. In the South, they learned about the events in the capital belatedly. On December 29, the Chernigov regiment led by S. Muravyov-Apostol rebelled, but it was not possible to raise the entire army. On January 3, the regiment was defeated by government forces.

More details

Ryleev asked Kakhovsky early in the morning of December 14 to enter the Winter Palace and kill Nikolai. Kakhovsky initially agreed, but then refused. An hour after the refusal, Yakubovich refused to lead the sailors of the Guards crew and the Izmailovsky regiment to the Winter Palace.

On December 14, officers - members of the secret society were still in the barracks after dark and campaigned among the soldiers. By 11 a.m. on December 14, 1825, the Moscow Guards Regiment entered Senate Square. By 11 a.m. on December 14, 1825, 30 Decembrist officers brought about 3,020 people to Senate Square: soldiers of the Moscow and Grenadier regiments and sailors of the Guards naval crew.

However, a few days before this, Nikolai was warned about the intentions of the secret societies by the Chief of the General Staff I. I. Dibich and the Decembrist Ya. I. Rostovtsev (the latter considered the uprising against the tsar incompatible with noble honor). At 7 o'clock in the morning, the senators took the oath to Nicholas and proclaimed him emperor. Trubetskoy, who was appointed dictator, did not appear. The rebel regiments continued to stand on Senate Square until the conspirators could come to a common decision on the appointment of a new leader.

Inflicting a mortal wound on M. A. Miloradovich on December 14, 1825. Engraving from a drawing owned by G. A. Miloradovich

Hero of the Patriotic War of 1812, St. Petersburg military governor-general, Count Mikhail Miloradovich, appearing on horseback in front of the soldiers lined up in a square, “said that he himself willingly wanted Constantine to be emperor, but what to do if he refused: he assured them that he himself saw the new renunciation and persuaded them to believe it.” E. Obolensky, leaving the ranks of the rebels, convinced Miloradovich to drive away, but seeing that he was not paying attention to this, he easily wounded him in the side with a bayonet. At the same time, Kakhovsky shot the Governor General with a pistol (the wounded Miloradovich was taken to the barracks, where he died that same day). Colonel Sturler and Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich tried unsuccessfully to bring the soldiers into obedience. Then the rebels twice repulsed the attack of the Horse Guards led by Alexei Orlov.

A large crowd of St. Petersburg residents gathered on the square and the main mood of this huge mass, which, according to contemporaries, numbered in tens of thousands of people, was sympathy for the rebels. They threw logs and stones at Nicholas and his retinue. Two “rings” of people were formed - the first consisted of those who came earlier, it surrounded the square of the rebels, and the second ring was formed of those who came later - their gendarmes were no longer allowed into the square to join the rebels, and they stood behind the government troops who surrounded the rebel square. Nikolai, as can be seen from his diary, understood the danger of this environment, which threatened great complications. He doubted his success, “seeing that the matter was becoming very important, and not yet foreseeing how it would end.” It was decided to prepare crews for members of the royal family for a possible escape to Tsarskoe Selo. Later, Nikolai told his brother Mikhail many times: “The most amazing thing in this story is that you and I weren’t shot then.” [source not specified 579 days]