“Arbitrariness” was the assessment given by Ambassador Ashraf Sultan, spokesman for the Egyptian Cabinet of Ministers, of the situation that arose following negotiations between Egypt and Ethiopia around the Renaissance Dam crisis, when the latter refused to recognize the conclusions of the advisory bureau’s report. At the same time, Dr. Muhammad Abd al-Ati, Egypt's Minister of Water Resources and Irrigation, said that the tripartite ministerial technical commission for the construction of the Renaissance Dam had not agreed on the reliability of the introductory report of the consulting firm tasked with completing two impact studies. Renaissance Dam on the countries at the mouth of the Nile. The report was discussed at a meeting held in Cairo on November 11-12 with the participation of the water ministers of Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia.

Since the beginning of the crisis several years ago, some states have made their position clear regarding the construction of the Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile. One such state is Saudi Arabia. Yesterday, Ahmed Abu Zeid, spokesman for the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said that Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry and his Saudi counterpart Adel Al-Jubeir discussed the issue of the Renaissance Dam. Abu Zeid explained that Saudi Arabia is monitoring the development of the crisis and understands Egypt's concerns, noting that "Al-Jubeir emphasized the Saudi side's understanding of the need to follow the principles of international law in this matter."

Context

Is there a war coming over the Nile waters?

NoonPost 05/05/2017 At the end of August, German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel offered his country's mediation in resolving the crisis in relations between the Nile Basin states. This is the first intervention by a European power in the long-running crisis.During a press conference with Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry, Sigmar Gabriel said that "any projects in the Nile Basin must take into account the interests of Egypt, and Germany is ready to act as a mediator between the different parties in this matter."

It is worth mentioning that in June the G20 Africa Partnership conference was held in Germany, following which it was promised to increase investments in most African countries, including Ethiopia. According to experts, Germany will provide assistance to Ethiopia in the field of technology and electronics, and will provide millions of dollars in financial assistance.

Although America has not officially stated its position, in March US President Donald Trump decided to reduce US subsidies to Ethiopia, announcing cuts to the foreign aid program announced by Barack Obama in 2015 at the African Union meeting in Addis Ababa. Under this program, six African countries will be allocated seven billion dollars over five years to carry out electrification. In March, Ethiopia announced that construction work on the Renaissance Dam was 56% complete.

In February 2014, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov confirmed that Russia will do everything possible to solve the water crisis in Egypt. He also stated the need to come to an agreement acceptable to both parties in solving the problem of water supply and the consequences of the launch of the Revival dam. He noted that at the same time, Moscow will support Egypt in resolving the crisis and will intervene at the right time.

Since 2011, the Italian construction engineering company Salini Impregilo has been constructing the dam.

InoSMI materials contain assessments exclusively from foreign media and do not reflect the position of the InoSMI editorial staff.

The century of almost unchallenged Egyptian dominance on the Nile and its control over the region's vital resource, water, is coming to an end. The Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, the “millennium project” that Addis Ababa managed to implement during the years of post-revolutionary chaos in Egypt, promises Africa not only the most powerful hydroelectric power station on the continent, but also new wars for water.

Maria Efimova

Construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which began in 2011, is entering its final stage. The test launch of the first turbine of a hydroelectric power station on the Blue Nile, 20 km from the Ethiopian-Sudanese border, is scheduled to take place in 2017. The $4.8 billion project, which will result in a 6,000-megawatt hydropower plant, the most powerful in Africa and one of the most powerful in the world, should not only turn Ethiopia into the largest electricity exporter in the region (second after South Africa), but also help countries of the continent, two-thirds of whose population do not have access to electricity (the record holder in this regard is Ethiopia’s neighbor Uganda, where 15% of the population uses electricity).

Formally, today all 11 states of the Nile Basin support the Ethiopian “Millennium Project”. However, as the opening of the hydroelectric power station approaches, unresolved contradictions become increasingly apparent. Although Ethiopia signed a memorandum with Egypt and Sudan in March 2015, the only two downstream countries potentially affected by the dam, the 12 rounds of negotiations that followed have left little clarity on how the inevitable changes to the Blue Nile's flow will be resolved. , providing almost 60% of the annual volume of Nile waters. According to Vlast’s interlocutor at the Egyptian Foreign Ministry, who is familiar with the progress of the negotiations, “in fact, the process has reached a dead end, not a single demand of Cairo has been heard, while the problem of the distribution of Nile waters has never been as acute in the last century as it is today.”

Great Britain concluded an agreement with the King of Egypt and Sudan, Fuad I, in 1929, proclaiming Egypt’s “historical rights” to the Nile

Ethiopia, whose territory produces more than 85% of the Nile's annual flow (in addition to the Blue Nile, which originates in the Ethiopian Lake Tana, another 17% of the water comes from the Atbara and Sobat rivers, whose sources are in the Abyssinian Highlands), has long remained silent in the distribution of its water resources. At the beginning of the 20th century, Egypt’s almost undivided dominance on the Nile was consolidated. Great Britain, recognizing the key importance of water resources for Egypt and maintaining its control over the territory that formally left its protectorate in 1922, concluded an agreement with King Fuad I of Egypt and Sudan in 1929, proclaiming Egypt’s “historical rights” to the Nile. Sudan claimed its rights in the middle of the century, immediately after gaining independence, as a result of which to this day, according to the Egyptian-Sudanese treaty of 1959, Cairo takes 55.5 billion cubic meters annually (70% of the average annual volume), 18.5 billion cubic meters (20%) is due to Khartoum. The agreement between them categorically excludes the implementation of large projects on the Nile, similar to the Ethiopian hydroelectric power station, without the sanction of these two countries in the basin.

When Addis Ababa announced its plans to build a dam on the Blue Nile in 2009, Egypt was ready to prevent the reduction of its share of water by any means, including deploying troops in Sudan and attacking strategic targets in Ethiopia. This is evidenced by data from the private intelligence and analytical agency Stratfor published in 2012 by WikiLeaks, citing sources close to the former head of the Egyptian intelligence services, Omar Suleiman. According to the released documents, the military option was discussed especially actively in 2010, when, on the initiative of Addis Ababa, five more Nile Basin countries (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi and Rwanda) signed an agreement in Entebbe stipulating the possibility of redistributing water quotas and implementing large projects in spite of Cairo-Khartoum Treaty of 1959. On the territory of the basin countries that have joined the Entebbe Agreement, only 14% of the Nile flow is formed; they have no direct interest in the redistribution of the river’s waters, since the bulk of the water consumed is taken from the White Nile and the African Great Lakes, which contain a quarter of all fresh water on the planet. Therefore, changing the status quo was of interest to them primarily from the point of view of obtaining electricity at favorable tariffs, which the then Prime Minister of Ethiopia Meles Zenawi promised to the members of his newly formed East African coalition if successful.

Before his overthrow, Hosni Mubarak (pictured) prevented Ethiopia from starting construction of the dam by any means, including threatening to declare war

The Egyptian revolution benefited the project. Construction of the Ethiopian dam began literally two months after the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak. Sudan, which has always sided with Egypt, experienced division into two states in 2011 and did not respond to the start of construction.

In June 2013, when the Ethiopian Parliament ratified the Entebbe Agreement, given Egypt's internal problems, military action, although opaquely hinted at by the Egyptian authorities, looked unlikely. President Mohamed Morsi tried to influence the Ethiopian government through Islamist rebel organizations, whose leaders, based in particular in Khartoum, carried out several anti-government actions in the Ethiopian capital. However, even then it was clear that the situation was out of Cairo’s control. The effect of Mohammed Morsi's bellicose rhetoric was soon negated by the fact that literally a few weeks after a high-level diplomatic scandal, a native of the Muslim Brotherhood movement was removed from power as a result of a military coup led by the current president, Field Marshal Abdel-Fattah al. - Sisi.

During the years of instability in Egypt, the Italian company Salini Construttori managed to complete the construction of the Ethiopian hydroelectric power station by half, and the current government of the country was faced with a fait accompli.

The conciliatory rhetoric of Egypt's new leader, who in 2015 signed an agreement approving the construction of the Ethiopian dam, which local media called a historic turn in the state's position, can be explained, in addition to internal ones, by two external factors - a sharp change in Sudan's approach and the lack of real, rather than declarative, support from Cairo's strategic partner - Saudi Arabia.

Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir actually violated the agreement with Cairo when, against the backdrop of chaos in Egypt in December 2013, he signed 14 new agreements with Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn in Khartoum regarding security, the creation of a free trade zone, investment, and the supply of electricity to Sudan after the construction of the Ethiopian dam.

It became clear that in the current circumstances, the old agreement with Cairo, whose diplomatic influence was melting before our eyes, could bring Khartoum much less benefit than the Ethiopian dam, which promised certain bonuses, in addition to cheap electricity. The largest state in Africa, with a population of 40 million people and an annual growth rate of 2.2%, relies mainly on agriculture, which in turn depends on irrigation. In fact, Sudan has always received less than its quota (5-6 billion cubic meters out of 18.5 go to Egypt). The bulk of the Nile's annual volume of water, generated during the rainy season on the Abyssinian Highlands, passed through Sudanese territory for only a few weeks a year in a powerful flow, from which the country's small dams were not able to retain sufficient water for a long period. When the Ethiopian dam is completed, experts say it will stabilize the flow so that Sudan can take its full share for year-round irrigation, which is expected to even increase the area of irrigated land. In addition, it is likely that the Ethiopian dam's silt retention will increase the service life of Sudanese dams.

In addition to these considerations, political factors could also play a role. Internationally isolated and persecuted by the International Criminal Court, Omar al-Bashir could count on some dividends from the US and China supporting the project (which allocated at least $1 billion for the construction of power lines from the Ethiopian hydroelectric power station).

Riyadh, which generously sponsors Egypt as its support in the confrontation with Iran and its allies, is in no hurry to take practical steps to defend the interests of its ally in the Nile issue. Saudi investments in Sudan have grown to $16 billion, mainly in the development of agriculture and the construction of new dams (the Saudis allocated $1.7 billion for this project alone last year), which in the future will allow Sudan not only to take its share of water in full , but also probably increase it at the expense of Egypt.

Egyptian farmers fear that the construction of the Ethiopian dam will lead to a shortage of Nile water for agricultural needs.

Although the Ethiopian project is almost completed, an objective and comprehensive assessment of its environmental impact and potential damage to the riparian states has not yet been carried out. Under the current agreement between Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt, in October 2016, two French companies - Artelia group and BRL Ingenierie - must complete a study that will determine the potential damage to neighboring countries from the Ethiopian dam. However, there are no guarantees that this will allow us to draw an adequate picture—many details of the project remain unknown.

Last December, BRLi's Dutch subcontractor, Deltares, refused to assess the potential damage. Cairo, as the Egyptian Foreign Ministry told "Authorities", is confident that the reason was delays on the Ethiopian side and Addis Ababa's attempts to hide the necessary data. The Deltares office did not confirm this information, citing as the reason that the company was placed by members of the tripartite committee in conditions in which an “objective and independent” assessment was impossible.

Ethiopian experts, who used computer simulations to predict the possible consequences, acknowledge that filling the reservoir behind the dam - at 74 billion cubic meters, slightly less than the Nile's average annual flow - would reduce the amount of water Egypt receives by at least during the first four years of filling the lake. True, according to these data, Egypt will feel the damage only if the filling of the reservoir begins in dry years (in years of heavy rains, the annual flow of the Nile can increase one and a half times).

In addition, this could lead to power outages at the Aswan High Dam, with its output reduced by at least 6% due to low water levels in Lake Nasser (Aswan Reservoir). These conclusions were revised in 2014 by a group of international experts, recommending more thorough and detailed studies and recognizing the methodology as imperfect.

According to the most gloomy forecasts made by the Egyptians themselves, within six years, which are allotted to fill the water reservoir, the country will receive on average 30% less than its annual norm, after the construction of the dam - by 20%, and the electricity production of the Aswan hydroelectric power station may decrease by 40%. Egypt also fears that the Ethiopian dam's silt retention will force Sudan to increase the fertility of its soils with pesticides, which will affect the quality of water flowing into the country. A drop in the water level in Lake Nasser could be a serious blow to the economy also because it would damage the Toshka project revived by Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, which began during the time of Hosni Mubarak. We are talking about the construction of a system of canals to transfer water from Lake Nasser for irrigation in the southwest of the country. The Southern Valley Development Project involves irrigating large areas of the Western Desert, which will require approximately 5.5 billion cubic meters of water from Lake Nasser. 85% of Egypt's Nile water is used for irrigation, and the new irrigation project, if it fails, will only worsen the country's water problems. The country of 82 million people requires 30% more water than it receives, and with Egypt's population projected to be around 120 million over the next 25 years, the country's needs will increase significantly.

The progress of negotiations on the Ethiopian dam significantly undermines the authority of President al-Sisi among the Egyptians. Thus, after a wave of indignant comments in the media and social networks, the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation declared its reports about the discovery of new sources of fresh water in the Nubian Aquifer (located in Libya, Egypt, Sudan and Chad) to be misunderstood. The public saw government reports as an attempt to distract attention from failures in the negotiation process after water experts recalled that the total volume of Egypt's groundwater had long been estimated, and the government had already reported four years ago the "miraculous" discovery of groundwater in considered to be the waterless Qattara lowland, but since then this discovery has not been remembered again.

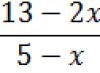

As Vlast's diplomatic sources reported, today one of Egypt's main demands is to double the time it takes to fill the reservoir behind the dam (Ethiopia plans to take five to six years for this process). Among the measures being discussed are partial filling, as well as reducing the reservoir of the auxiliary dam needed in case of emergencies by half (from 60 billion cubic meters to 30 billion), as well as obtaining guarantees that the accumulated water will not be used for irrigation. Cairo appeals to its “historical right” to the Nile, to existing treaties with Great Britain and Sudan, which only it itself now actually recognizes, as well as to international laws.

As Ayman Musa, a spokesman for the Egyptian Embassy in Moscow, told Vlast, Addis Ababa has still not met Egyptian demands. “Egypt has confirmed many times its readiness to involve various international institutions for a settlement, but Ethiopia wants to speed up construction so that the dam becomes a fait accompli, and thereby deprive Egypt of the right to justice,” says Vlast’s interlocutor.

International law in this area, however, does not give an unambiguous answer to the question of the rights of certain states in the use of transboundary rivers, stipulating them only in the most general form. The fundamental norm of the legal regime in this area is the principle of reasonable and equitable use, according to which each basin state has the right, within its territory, to a share in receiving benefits from the use of the waters of this basin.

Experts in the field of hydropower interviewed by Vlast are confident that it is theoretically possible for an agreement between the countries of the basin on a regime that would ensure the old agreements and would allow the Egyptian share of water not to decrease when the reservoir is filled. “To establish such a regime, it would be possible to carry out the bulk of the filling during heavy floods, while in dry years limiting the filling of the reservoir. All this can be accurately calculated, but will depend, of course, not least on considerations of economic feasibility,” says the former Chief hydraulic engineer of the research institute "Teploelektroproekt" Sergei Zisman.

Judging by the fact that Ethiopia plans to complete the project in a short time, it will have to use the most unfortunate moment to fill the reservoir: in 2015, the country experienced a drought, which, according to UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, could become the longest and most severe in recent years. 30 years old.

According to Jason Mosley, an expert on East Africa from the British think tank Chatham House, for the Ethiopian authorities, the speedy launch of the Grand Renaissance Dam is not only an economic issue. “The project has enormous symbolic significance. It is presented as one of the main components of the national development strategy. The government promises that the country will stop relying on foreign aid, as it does today, and will become economically independent,” says the expert. The country, with one of the lowest GDP per capita since the early 2000s, has experienced economic growth of 11% per year, which has led to a third reduction in the number of people living below the poverty line over the past 15 years. According to Jason Mosley, maintaining this trend is the key to the political stability of Ethiopia and the entire region.

Ethiopia-Egypt dispute raises potential for new conflicts in region

Although reports on the details of financing the project vary (according to official data, in addition to the money that Chinese banks are ready to allocate for the construction of power transmission lines, Ethiopia used its own funds, selling bonds to the population; according to other sources, the participation of foreign capital was more significant), Ethiopia needs both you can recoup your investment as quickly as possible. The World Bank projects that Addis Ababa will generate $1 billion in revenue annually, which would recoup the cost of the project within five years.

The dispute between Ethiopia and Egypt potentially threatens new conflicts in the region. In the current circumstances, in fact, the only trump card remaining in the hands of Cairo, apart from the dubious effectiveness of the “soft power” tool - the mediation of the Egyptian Coptic patriarch, who is actively establishing relations with the Ethiopian Copts - are connections with approximately 12 rebel separatist groups in Ethiopia, which were established during the time of Hosni Mubarak, including through Egypt's allies in Eritrea. Egypt, which is actively fighting Islamists within the country, may try to use the religious factor, using Muslims, who make up about a third of Ethiopia's population, to put pressure on the country's Christian government.

Relations between Egypt and Ethiopia have sharply deteriorated against the backdrop of Addis Ababa's construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam hydroelectric station in the upper reaches of the Blue Nile.

Nothing illustrates the extent of Egypt's dependence on the Nile like a view of the country from above. Against the backdrop of vast deserts, the river and its cultivated banks appear as a narrow green ribbon, making its way to the north, where it reaches the sea. About 94 million Egyptians live here. The rest of the country remains uninhabited sandy territory, writes the Financial Times.

But Cairo now fears that Ethiopia's plan to build a huge hydroelectric dam on the Nile will reduce the country's access to water. At the heart of the dispute is Egypt's fear that once the dam is built, the country will receive less than the annual 55.5 billion cubic meters of water that is the minimum requirement for the population. However, Ethiopia is confident that the dam will not have an adverse impact on countries located downstream of the Nile.

Tensions between Cairo and Addis Ababa have increased greatly in recent weeks. In particular, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi said that the Nile “is a matter of life and death” for his country, and that “no one can encroach on Egypt’s share of water.” In response, Ethiopia countered that the dam was a matter of life and death for it as well.

In Sudan, however, it is speculated that Cairo's anger is because the dam will allow Khartoum to use more water instead of allowing it to flow downstream to Egypt.

In November, negotiations took place between the three countries, which tried to reach an agreement on the construction of the dam, but this meeting did not lead to anything.

On Tuesday, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry flew to Addis Ababa for regular talks. He highlighted Egypt's concerns over water availability, calling the issue too sensitive for Cairo to rely solely on "promises and claims of good intentions." He also proposed making the World Bank a “neutral party” in the negotiations.

Let us recall that in 2011 Ethiopia unveiled a project for the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam hydroelectric station in the upper reaches of the Blue Nile, a right tributary of the Nile, near the border with Sudan. Downstream Egypt fears the dam will affect Nile water levels and cause drought. Now Egypt receives about 70% of the Nile waters, RIA Novosti reports.

Earlier, an agreement was finally reached between Egyptian and Ethiopian diplomats that Ethiopia would continue the construction of the hydroelectric power station, but would take into account the interests of Egypt. Cairo, in turn, confirmed Addis Ababa's right to economic development.

16.01.2014 16:01

In 2011, as soon as the revolution took place in Egypt and Mubarak was in prison, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania initiated the redistribution of the Nile water intake. Egypt and Sudan refuse to sign a new agreement that effectively threatens their existence, citing international agreements signed earlier.

The Egyptian leadership hopes that it will be possible to preserve the “historical rights” that are confirmed by the 1929 treaty between Egypt and the British Empire. The treaty gives the country veto power over any projects in the upper Nile. According to a treaty signed in 1959 between Egypt and Sudan, the two states take 90% of the Nile's water intake. The actions of African states, and, first of all, Ethiopia, are aimed at destroying the Arab monopoly on the Nile. Ethiopia does not face a water shortage problem - the dam should provide the country with electricity.

Every year, on January 9, Egyptians commemorate the construction of the Aswan Dam, built during the reign of President Gamal Abdel Nasser. Construction of the dam began in 1960 and was put into operation in 1971. The total cost of construction was more than $1 billion, most of which was financed by the USSR. The dam's capacity is 160 billion cubic meters of water.

The reservoir formed by the dam was called “Lake Nasser”.

However, the 54th celebration of the national event was overshadowed by fear and apprehension about what awaits the country in connection with the implementation of a large-scale project in the south, in neighboring Ethiopia. Currently, the construction of the “Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam” is taking place on the Blue Nile River (the most powerful, right tributary of the Nile) and there is no doubt that it will have a direct and extremely detrimental effect on Egypt’s water supply. In this case, the Aswan Dam could be out of action for at least two years. The Ethiopian dam is scheduled to open in 2017. With a capacity of 6,000 MW, it will be the most productive hydroelectric power plant in Africa.

Experts' warnings about the harm posed by the new Ethiopian dam are causing real panic among Egyptians. The situation has become so tense that many now believe that the Aswan Dam will certainly collapse as soon as construction is completed in Ethiopia.

But even without the panic that the Egyptian media are sowing among citizens, the country’s transitional government itself is extremely concerned about the inevitable negative prospects. There is information that at one of the military councils, now ex-President Morsi suggested that the army leadership begin bombing a facility under construction in Ethiopia. During the Mubarak years, ships carrying construction equipment to Ethiopia were stopped by the Egyptian army, and the world was told that the next shipment of cargo for this project would be destroyed by the entire Egyptian army. From that moment on, the project was frozen.

Recently, at an emergency meeting of the Egyptian National Defense Council under the leadership of interim President Adly Mansour, politicians and leading experts discussed the consequences of the crisis and ways to minimize the negative consequences for Egypt in the event of the commissioning of the Ethiopian dam. Alaa al-Zawahiri, a member of a group of national experts studying the consequences of the dam, said that the dam would be able to receive no more than 74 billion cubic meters of water, which, in turn, would spell disaster for Egypt: the country would lose 60% of its agricultural land. Zawahiri added that the possible destruction of the Renaissance Dam will lead to the collapse of the Aswan Dam, and in fact, the whole of Egypt.

Mohamed Nassreddin, the former Minister of Water Resources and Irrigation of Egypt, believes that the construction of the Ethiopian dam will indeed lead to extremely dangerous consequences and will have a devastating impact on the Aswan Dam. In his opinion, as soon as the facility in Ethiopia becomes operational, the depth level of Aswan will begin to steadily decline, reaching 160 meters. In turn, this will lead to a drop in the amount of electricity it generates by 30-40%.

Nasreddin is convinced that the construction of the Ethiopian Millennium Dam is a powerful means in the political struggle for hegemony and influence on the African continent. According to the former minister, it all began with the triple aggression against Egypt in 1956, followed by Nasser's announcement of his intention to build the Aswan Dam and nationalize the Suez Canal. Then the United States sent a team of experts from the Bureau of Reclamation. Their task was to find places for the construction of 33 power electrical installations (and dams, respectively) on the banks of the Nile. Political objective: stop plans to build the Aswan Dam and deprive Egypt of water. These experts presented their report in 1958, but practical implementation was delayed indefinitely. And today, during the most difficult period in the history of the Egyptian state, this program to strangle Egypt was put into action.

The President of the Aswan Dam Builders Association, Saad Nasser, criticized the construction process of the Ethiopian dam. The project is being implemented in conditions of almost complete secrecy. None of the interested parties has any information either on the results of preliminary studies and recommendations, or on technical and economic parameters. According to Nasser, all this secrecy is needed in order to hide the true consequences of the commissioning of this facility for the region until the last minute of construction. Especially in the actual volumes of water that will be withdrawn from the Aswan Dam flow once the Renaissance Dam begins operation. He emphasized that the Aswan High Dam was built at a time when countries bordering the Nile acted according to the circumstances of the time. All actions were based on relevant international treaties.

|

| World water scarcity map |

The current Minister of Water Resources and Irrigation, Mohamed Abdul Muttalibah, in an interview with Al-Monitor stated the following: “Egypt at all levels will strive to thwart this threat (to the operation of the Aswan Dam).

The dam was included in the list of the most important projects built in the world in the 20th century and is ranked first out of 122 [according to an international report published in 2010]. It “allows Egypt to maintain strategic water reserves at adequate levels.”

In his speech, the minister said that on the anniversary of the construction of the Aswan Dam, he would like to reassure all Egyptians that the functioning of the dam has been protected. This is, in particular, evidenced by Egypt's refusal to participate in the latest meetings in Khartoum due to the fact that Ethiopia does not guarantee water quotas for Egypt and the continued effective functioning of the Aswan Dam after the commissioning of the Millennium Dam. But will Egypt be able to stop construction? Will war be the only way to turn one catastrophe (water shortage in Egypt) into another - a large-scale regional conflict?

Egypt is experiencing a population boom. Already today, about 85 million people live in Egypt. Its population is projected to reach 135 million inhabitants by 2050. But even today there is no longer enough water in Egypt. It is easy to imagine what kind of humanitarian catastrophe the successful implementation of the Ethiopian project could lead to.

It would seem worth rejoicing for Ethiopia, which is building a huge dam on the Nile. The Ethiopian peasants are really rejoicing, but in Cairo there are thunder and lightning. In Egypt they are afraid that due to the new dam and especially as a result of the filling of the reservoir, less water will flow to them. Although both countries could benefit from the Grand Renaissance Dam if they wanted, both Cairo and Addis Ababa are determined.

Blood for the Nile

In Egypt, the proposal to bomb the Renaissance Dam is being discussed at the highest level. After the government meeting at which this issue was discussed, the President Mohamed Morsi promised the whole country to “protect every drop of the Nile with our blood.” Egypt, he said, does not want war, but is ready for it.

In Ethiopia, on whose territory the main sources of the great river are located, they are also in a militant mood. In response to Cairo's threats, its parliament ratified a new treaty regulating relations between the countries through whose territory the Nile flows, replacing the old one concluded back in 1929 with the active mediation of Great Britain, the dominant power in eastern Africa in those years. That agreement made Egypt almost the absolute owner of the great river. The document obliged the remaining 9 Nile countries not to take any actions that could reduce the flow of water in the Nile. Of the estimated 84 billion cubic meters of water flowing along the Nile per year, the old treaty guarantees Egypt 55.5 billion.

For seven decades, the Nile countries endured the dictates of Egypt and Sudan, which joined it. In 1959, Cairo and Khartoum signed an agreement under which Sudan was allocated 18.5 billion cubic meters of Nile water. By the way, this time Khartoum, for almost the first time in half a century, did not support Cairo in the dispute over the Nile. A week and a half ago, Ethiopia joined five other countries located on the banks of the Nile: Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda, which also ratified a new agreement that cancels the old one.

Addis Ababa says it delayed ratification out of respect for the Egyptian people. Ethiopia was waiting for a government to appear in Egypt.

The construction of the Renaissance Dam is not a surprise for Cairo. This dam in northwestern Ethiopia, near the border with Sudan, has been planned since the 1960s. However, Addis Ababa officially announced the final decision to build it only in March 2011. The project's capacity is estimated at 5,250 megawatts. It must double Ethiopia's electricity generation. The dam is now 20% complete.

Useful Conflict

Despite the fact that the Nile flows through 10 countries, the construction of the dam will affect only three of them: Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan. The Nile supplies Egypt with 95% of its water supply. It is not surprising that two years ago, when the Ethiopians began building the dam without first consulting Cairo, which they were obliged to do under the 1929 treaty, the Egyptians became alarmed.

It so happens that no country is now ready for a serious conflict. The revolution gave Egypt a weak government. There is a strong economic and political crisis in the Land of the Pharaohs.

Ethiopia hardly needs a conflict either, which, by the way, is already suffering for its initiative. The World Bank and other international lenders strongly disapprove of large water projects that involve multiple countries without their approval. As a result, Addis Ababa has to finance the project, costing, according to various estimates, from 4.3 to 4.8 billion dollars, with its own resources. The government, naturally, siphons money from the population, which is forced to buy bonds.

Another conflict over the Nile is surprising because the dam could benefit both countries. Ethiopia, with its abundant rainfall and many high mountains, is an ideal location for hydropower development. However, 83% of the country's population lives without electricity. Revival will not only provide Ethiopia with electricity, but will also allow it to sell surpluses to its neighbors, including Egypt. It should be borne in mind that energy generated from water is much cheaper than that obtained by burning solid fuel. In Egypt, 90% of electricity is generated using this expensive method.

Ethiopia is interested in allaying Egypt's fears about the runoff because without financial help from Cairo, it will not be able to complete construction without completely paralyzing its economy. It is beneficial for Cairo to let Addis Ababa complete the dam because it will not only provide it with cheap electricity, but will also improve the standard of living in Ethiopia, thereby increasing the market for Egyptian goods and services.

It turns out that everything comes down to the Egyptians’ concern about the flow. The Ethiopians tried to reassure Cairo by presenting a study by scientists who said the dam would not have much impact on downstream water flow. However, in Egypt they believe that one study is not enough to judge the possible consequences of construction. There is the possibility of a compromise that could reduce the intensity of passions. Ethiopia plans to fill the reservoir with 74 billion cubic meters of water within 5-6 years. As a gesture of goodwill, she could fill it more slowly and agree to more research into the impacts that the dam's construction might cause.