alphabets of UN member states.

Read more.

| Mongolian Cyrillic alphabet | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mongolian Cyrillic- alphabet of the Mongolian language based on the Cyrillic alphabet, adopted in the Mongolian People's Republic since 1941. Many other writing systems were used for the Mongolian language (see Mongolian scripts). Outside Mongolia, for example in China, they are still used today.

The modern Mongolian alphabet differs from the Russian alphabet by two additional letters: and.

Difference from previous systems

Rationalistically, the introduction of this alphabet was justified by the need to establish a direct correlation between the spoken phonetic norm and writing. It was believed that the Old Mongolian writing was inaccessible to ordinary people, since the word forms used in it were significantly outdated, and the study of writing required actually studying the Mongolian language of the Middle Ages, with a large number of letters and long-lost tense and case forms. Cyrillization was carried out on the basis of the so-called “clattering” Khalkha dialect (thus, the word “tea” during Cyrillization was finally assigned the phonetic form Mong. tsai, while in the old Mongolian h And ts did not differ). Also, in comparison with the old Mongolian orthography, the “zh” and “z”, “g” and “x” words of the soft series, “o” and “u”, “ө” and “ү” were clearly differentiated. The writing of borrowings from languages that do not have vowel harmony became more accurate, since the Old Mongolian letter automatically implied the identification of the phonetics of the entire word as a soft (front-lingual) or hard (back-lingual) series, which was most often identified by the first syllable.

The main omission of this orthography in relation to phonetics is that in some cases, without knowing the word in advance, there is no opportunity to differentiate sounds [n] And [ŋ] , since there is a special sign for [ŋ] No. This causes, in particular, a problem in the display of Chinese words and names, since in Mongolian words proper, “ь” is used, unlike the Russian language, in places where “i” has ceased to be pronounced, and is therefore rarely used where it is not implied syllable.

Story

The first experiments in using the Cyrillic alphabet for the Mongolian language belonged to Orthodox missionaries and became significant under the leadership of Nil of Irkutsk and Nerchinsky in the 1840s. Since then, a number of Cyrillic Orthodox church publications have appeared in various Mongolian languages, not using a single graphic standard.

In the 1990s, the idea of returning to the old Mongolian script was put forward, but for a number of reasons this transition was not realized. However, while maintaining the Cyrillic alphabet as the main written language of the country, the old Mongolian letter has again acquired official status and is used in state seals, and, at the request of the owners, on signs and company logos.

As a reaction to the assimilation of the Mongols of Inner Mongolia by the Chinese population, since the 1990s the Mongolian Cyrillic alphabet has also spread among them as the script of the unassimilated (that is, not sinicized in the field of language) Mongols of Mongolia. In Inner Mongolia, publications in the Mongolian Cyrillic alphabet began to appear, primarily reprints of works by authors from Mongolia. The popularity of this phenomenon is associated not only with aspects of national identity, but also with the temporarily greater friendliness of the computer environment to the Cyrillic alphabet compared to the vertically oriented Old Mongolian script.

ABC

| Cyrillic | MFA | Cyrillic | MFA | Cyrillic | MFA | Cyrillic | MFA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A a | a | And and | i | P p | p | H h | tʃ | |||

| B b | b | Thy | j | R r | r | Sh sh | ʃ | |||

| In in | w | K k | k | With with | s | sch sch | stʃ | |||

| G g | ɡ | L l | ɮ | T t | t | Kommersant | ||||

| D d | d | Mm | m | U y | ʊ | s s | i | |||

| Her | je | N n | n | Ү ү | u | b b | ʲ | |||

| Her | jɔ | Oh oh | ɔ | F f | f | Uh uh | e | |||

| F | dʒ | Ө ө | ɞ | X x | x | Yu Yu | jʊ | |||

| Z z | dz | Ts ts | ts | I I | ja |

Write a review about the article "Mongolian alphabet"

Notes

An excerpt characterizing the Mongolian alphabet

- How you loved them!.. Who are you, girl?My throat became very sore and for some time I could not squeeze out a word. It was very painful because of such a heavy loss, and, at the same time, I was sad for this “restless” person, for whom it would be oh, how difficult it would be to exist with such a burden...

- I am Svetlana. And this is Stella. We're just hanging out here. We visit friends or help someone when we can. True, there are no friends left now...

- Forgive me, Svetlana. Although it probably won’t change anything if I ask you for forgiveness every time... What happened happened, and I can’t change anything. But I can change what will happen, right? - the man glared at me with his eyes blue as the sky and, smiling, a sad smile, said: - And yet... You say I am free in my choice?.. But it turns out - not so free, dear... It looks more like atonement... Which I agree with, of course. But it is your choice that I am obliged to live for your friends. Because they gave their lives for me... But I didn’t ask for this, right?.. Therefore, it’s not my choice...

I looked at him, completely dumbfounded, and instead of “proud indignation” that was ready to immediately burst from my lips, I gradually began to understand what he was talking about... No matter how strange or offensive it may sound - but all this was the honest truth! Even if I didn't like it at all...

Yes, I was very painful for my friends, for the fact that I would never see them again... that I would no longer have our wonderful, “eternal” conversations with my friend Luminary, in his strange cave filled with light and warmth ... that the laughing Maria would no longer show us the funny places that Dean had found, and her laughter would not ring like a merry bell... And it was especially painful that instead of them this person, completely unfamiliar to us, would now live...

But, again, on the other hand, he did not ask us to interfere... He did not ask us to die for him. I didn't want to take someone's life. And now he will have to live with this heavy burden, trying to “pay off” with his future actions a guilt that was not really his fault... Rather, it was the guilt of that terrible, unearthly creature who, having captured the essence of our stranger, killed “right and left.”

But it certainly wasn't his fault...

How could it be possible to decide who was right and who was wrong if the same truth was on both sides?.. And, without a doubt, to me, a confused ten-year-old girl, life seemed at that moment too complicated and too many-sided to be possible. somehow decide only between “yes” and “no”... Since in each of our actions there were too many different sides and opinions, and it seemed incredibly difficult to find the right answer that would be correct for everyone...

– Do you remember anything at all? Who were you? What's your name? How long have you been here? – in order to get away from a sensitive and unpleasant topic, I asked.

The stranger thought for a moment.

- My name was Arno. And I only remember how I lived there on Earth. And I remember how I “left”... I died, didn’t I? And after that I can’t remember anything else, although I really would like to...

- Yes, you “left”... Or died, if you prefer. But I'm not sure this is your world. I think you should live on the “floor” above. This is the world of “crippled” souls... Those who killed someone or seriously offended someone, or even simply deceived and lied a lot. This is a terrible world, probably the one that people call Hell.

- Where are you from then? How could you get here? – Arno was surprised.

- It's a long story. But this is really not our place... Stella lives at the very top. Well, I’m still on Earth...

– How – on Earth?! – he asked, stunned. – Does this mean you’re still alive?.. How did you end up here? And even in such horror?

“Well, to be honest, I don’t like this place too much either...” I smiled and shuddered. “But sometimes very good people appear here.” And we are trying to help them, just as we helped you...

- What should I do now? I don’t know anything here... And, as it turned out, I killed too. So this is exactly my place... And someone should take care of them,” Arno said, affectionately patting one of the kids on the curly head.

The kids looked at him with ever-increasing confidence, but the little girl generally clung to him like a tick, not intending to let go... She was still very tiny, with big gray eyes and a very funny, smiling face of a cheerful monkey. In normal life, on the “real” Earth, she was probably a very sweet and affectionate child, beloved by everyone. Here, after all the horrors she had experienced, her clear, funny face looked extremely exhausted and pale, and horror and melancholy constantly lived in her gray eyes... Her brothers were a little older, probably 5 and 6 years old. They looked very scared and serious , and unlike their little sister, they did not express the slightest desire to communicate. The girl, the only one of the three, apparently wasn’t afraid of us, because having very quickly gotten used to her “newfound” friend, she asked quite briskly:

- My name is Maya. Can I please stay with you?.. And my brothers too? We have no one now. We will help you,” and turning to Stella and me, she asked, “Do you live here, girls?” Why do you live here? It's so scary here...

With her incessant barrage of questions and her manner of asking two people at once, she reminded me a lot of Stella. And I laughed heartily...

– No, Maya, we, of course, don’t live here. You were very brave to come here yourself. It takes a lot of courage to do something like this... You are truly great! But now you have to go back to where you came from; you have no reason to stay here anymore.

– Are mom and dad “completely” dead?.. And we won’t see them again... Really?

Maya’s plump lips twitched, and the first large tear appeared on her cheek... I knew that if this was not stopped now, there would be a lot of tears... And in our current “generally nervous” state, this was absolutely impossible to allow...

– But you’re alive, aren’t you?! Therefore, whether you like it or not, you will have to live. I think that mom and dad would be very happy if they knew that everything was fine with you. They loved you very much...” I said as cheerfully as I could.

The main asset of any people is its language and writing. They give originality, allow you to establish national identity and stand out from others. Over their centuries-old history, the Mongols managed to try about ten different alphabets; now these people mainly use the Cyrillic alphabet. How did the descendants of the conquerors who founded the Golden Horde switch to a writing system similar to Russian? And why not Latin or Old Mongolian script?

Many alphabets, one language

Many have tried to develop an alphabet suitable for the Mongolian language and all its dialects. The legendary commander Genghis Khan himself, when creating a huge empire, was concerned with the need to establish a document flow in order to record orders and draw up contracts.

There is a legend that in 1204, after defeating the Naiman tribe, the Mongols captured a scribe named Tatatunga. By order of Genghis Khan, he created a writing system for the conquerors based on his native Uyghur alphabet. All documents of the Golden Horde were compiled using the developments of a captive scribe.

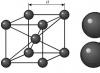

A characteristic feature of Old Mongolian writing is its vertical orientation: words are written from top to bottom, and lines are arranged from left to right. Some researchers explain this fact by the fact that it was easier for a warrior galloping on his war horse to read scrolls compiled in this way.

In the 90s of the 20th century, in the homeland of Genghis Khan, the old Mongolian script was returned to official status, but its scope of application is limited to company logos and names of organizations, since this alphabet is outdated and does not correspond to modern pronunciation. In addition, the old Mongolian script is not convenient for working on a computer.

However, a modified version of this alphabet is used in Inner Mongolia, a region of China where the main population is the descendants of the legendary conquerors.

Subsequently, there were several more variants of Mongolian writing. For example, at the end of the 13th century, the Tibetan monk Pagba Lama (Dromton Chogyal Pagpa) developed the so-called square script based on the symbols of Chinese phonetics. And in 1648, another monk, Zaya Pandita of Oirat, created todo-bichig (clear writing), focusing on Tibetan writing and Sanskrit. The Mongolian scientist Bogdo Dzanabazar developed soyombo at the end of the 17th century, and the Buryat monk Agvan Dorzhiev (1850-1938) developed vagindra. The main goal of these scientists was to create an alphabet most suitable for translating sacred texts into Mongolian.

Writing is a political issue

The use of certain symbols to record a language is not so much a matter of convenience and linguistic conformity as it is a choice of the sphere of political influence. By using one alphabet, peoples inevitably become closer and enter into a common cultural space. In the twentieth century, Mongolia, like many other countries, actively sought self-determination, so writing reform was inevitable.

Revolutionary transformations in this Asian state began in 1921, and soon socialist power was established throughout Mongolia. The new leadership decided to abandon the old Mongolian script, which was used to translate religious texts ideologically alien to the communists, and switch to the Latin alphabet.

However, the reformers encountered strong resistance from many representatives of the local intelligentsia, some of whom were supporters of modifying the old Mongolian script, while others argued that the Latin alphabet was not suitable for their language. After accusations of nationalism and a wave of repressions in the second half of the 30s of the twentieth century, the linguistic reformers simply had no opponents left.

The Latin alphabet was officially approved in Mongolia on February 1, 1941, and a modified version of this alphabet began to be used for printing newspapers and books. But less than two months passed before this decision of the country’s leadership was canceled. And on March 25, 1941, the people were announced about the imminent transition to the Cyrillic alphabet. Since 1946, all media began to use this alphabet, and since 1950, legal documents began to be drawn up in it.

Of course, the choice in favor of the Cyrillic alphabet was made by the Mongolian authorities under pressure from the USSR. At that time, the languages of all the peoples of the RSFSR, Central Asia and neighboring states, which were under the strong influence of Moscow, were ordered to be translated into the Cyrillic alphabet.

Only the inhabitants of Inner Mongolia, which is part of the People's Republic of China, still have the same vertical writing system. As a result, representatives of one nation, separated by a border, use two different alphabets and do not always understand each other.

In 1975, under the leadership of Mao Zedong, preparations began to translate the language of Inner Mongolia into the Latin alphabet, but the death of the head of the Chinese Communist Party prevented this plan from being realized.

Now some Mongolians who are citizens of the PRC use the Cyrillic alphabet to emphasize their national identity as a counterbalance to the assimilating influence of the Chinese authorities.

Cyrillic or Latin?

Unlike the Russian alphabet, the Mongolian version of the Cyrillic alphabet has two additional letters: Ү and Ө. The developers managed to distinguish between the dialect sounds of the sounds Ch and C, Zh and Z, G and X, O and U, Ө and Ү. And yet, this type of writing does not provide a complete correlation between writing and pronunciation.

Although the Latin alphabet also cannot be called a suitable alphabet for the Mongolian language, this type of writing has its drawbacks. Not all sounds are the same when written and pronounced.

In the 1990s, in the wake of the rejection of communist ideology and the search for a further path of development, there was an attempt to return the old Mongolian writing, but it ended in failure. This alphabet no longer corresponds to the trends of the times, and converting all scientific terms, formulas, textbooks and office work in the country to a vertical spelling turned out to be an impractical, costly and labor-intensive process. Such a reform would take a lot of time: we would have to wait for representatives of the next generation, educated in Old Mongolian, to start working as teachers.

As a result, having given the original alphabet the status of official, the Mongols use it only for decorative purposes, continuing to write in Cyrillic, although from time to time there are calls in the country to switch to the Latin alphabet.

Wanting to demonstrate their national independence, at the end of the 20th and beginning of the 21st centuries, the states of Central Asia abandoned the Cyrillic alphabet, which was imposed on them during the Soviet era. Even in Tatarstan, which is part of Russia, there was talk of writing reform. This process is actively lobbied by Türkiye, which switched to the Latin alphabet in 1928, as well as its NATO allies - Great Britain and the USA, who are interested in spreading their cultural influence in Asia.

However, Mongolia's transition to the Latin alphabet is unlikely for several reasons.

Firstly, this country is not one of the Turkic-speaking states, unlike its neighbors from Central Asia, and therefore the opinion of official Ankara does not matter much in Ulaanbaatar.

Secondly, the Mongols do not have a strong desire to distance themselves from Russia. Despite the repressions of the 30s of the twentieth century, this country also remembers the good things that were done with the help of the USSR: the construction of enterprises, hospitals, educational centers, and infrastructure facilities.

Thirdly, Mongolians fear the growing influence of China, which is seeking to assimilate all neighboring peoples. The Cyrillic alphabet serves as a kind of cultural buffer that prevents the Mongols from being deprived of their national identity.

In addition, as we mentioned above, the Latin alphabet is also not entirely suitable for the Mongolian language, just like the Cyrillic alphabet. Therefore, residents of this country do not see much sense in changing one alphabet for another.

Material from Wikipedia - the free encyclopedia

Mongolian scripts- writing systems of different origins that arose at different times and were used to record the Mongolian language.

Mongolian scripts- writing systems of different origins that arose at different times and were used to record the Mongolian language.

The attention of the great powers brought to life, beginning in the mid-19th century, a number of projects for writing systems based on the Latin and Cyrillic alphabet. In 1940, as a result of rapprochement with the Soviet Union, Mongolia switched to the Cyrillic alphabet, which currently remains the main writing system in the country, although projects to switch to the Latin alphabet were considered.

Old Mongolian writing

(Classical Mongolian script)

According to one legend, at the beginning of the formation of the Mongol Empire, about a year, Genghis Khan defeated the Naimans and captured the Uyghur scribe, Tatatunga, who adapted the Uyghur alphabet (going back through the Sogdian to the Syriac alphabet) to write the Mongolian language.

According to another legend, Genghis Khan demanded the creation of a written language based on the archaic pronunciation of his times, so that the written language would unite speakers of various dialects of that time. This legend explains the characteristic discrepancy between the spelling norms of Old Mongolian writing and pronunciation norms. In turn, this discrepancy served as the official justification for the Cyrillization of the Buryat and Mongolian languages.

Its most notable feature is the vertical direction of writing - it is the only vertical writing system in active use, in which lines are written from left to right.

This script, with minor changes, has survived to this day and is used by the Mongols of the People's Republic of China, primarily in Inner Mongolia.

In the 1990s. in Mongolia, the old Mongolian letter was returned to official status, but its scope remained limited.

Todo-bichig

("clear writing")

Vagindra

A type of Old Mongolian writing, created in 1966 by the Buryat monk Agvan Dorzhiev (-). Its task was to eliminate ambiguities in spelling and make it possible to write Russian along with Mongolian. The most significant innovation was the elimination of variability in the shape of symbols depending on position - all signs were based on the middle variant of the Old Mongolian script.

Square letter

(pagba, dorvoljin bichig, hor-yig)

Classical Mongolian writing was not suitable for languages with a different phonology from Mongolian, in particular Chinese. Around the year the founder of the Yuan dynasty, the Mongol Khan Kublai Khan, ordered the Tibetan monk Dromton Chogyal Phagpa (Pagba Lama) to develop a new alphabet that was to be used throughout the empire. Pagpa used the Tibetan script, adding symbols to reflect Mongolian and Chinese phonetics, and set the order of writing characters from top to bottom and lines from left to right, similar to the old Mongolian one.

Writing fell into disuse with the fall of the Yuan Dynasty in the year. After this, it was used sporadically as a phonetic notation by the Mongols who studied Chinese writing, and also until the 20th century by the Tibetans for aesthetic purposes as a modification of the Tibetan alphabet. Some scholars, such as Gary Ledyard, believe that it had a direct influence on the Korean Hangul alphabet.

Soyombo

Soyombo is an abugida created by the Mongolian monk and scholar Bogdo Dzanabazar at the end of the 17th century. In addition to Mongolian proper, it was used to write Tibetan and Sanskrit. A special sign of this script, soyombo, has become the national symbol of Mongolia and is depicted on the state flag (from the year), and on the coat of arms (from the year), as well as on money, postage stamps, etc.

Soyombo is an abugida created by the Mongolian monk and scholar Bogdo Dzanabazar at the end of the 17th century. In addition to Mongolian proper, it was used to write Tibetan and Sanskrit. A special sign of this script, soyombo, has become the national symbol of Mongolia and is depicted on the state flag (from the year), and on the coat of arms (from the year), as well as on money, postage stamps, etc.

Dzanabazar's goal was to create a script suitable for translating Buddhist texts from Sanskrit and Tibetan - in this capacity it was widely used by him and his students. Soyombo appears in historical texts as well as temple inscriptions.

Horizontal square letter

Cyrillic

Foreign writing systems

Until the 13th century, Mongolian was often written using foreign writing systems. In areas conquered by the Mongol Empire, local scripts were often used.

The Mongolian language was often transcribed in Chinese characters - in particular, they recorded the only surviving copy of the Secret History of the Mongols. B.I. Pankratov provides information indicating that the hieroglyphic transcription of this and a number of other monuments was made to teach Chinese diplomats and officials the Mongolian language.

Representatives of the peoples of the Middle East and Central Asia hired by the Mongols for administrative positions often used Persian or Arabic alphabets to write Mongol-language documents.

With the strengthening of the position of Buddhism among the Mongols since the 17th century, a significant number of Mongolian monks educated in the Tibetan tradition appeared. They used the Tibetan alphabet, without modifying it, to record their own works, including poetry, while largely transferring the spelling norms of the Old Mongolian alphabet into their records.

See also

Write a review about the article "Mongolian writings"

Notes

Literature

- Kara, Gyorgy. Books of Mongolian nomads: Seven centuries of Mongolian writing. Moscow, “Science”, 1972.

Links

An excerpt characterizing Mongolian writings

- Where is the sovereign? where is Kutuzov? - Rostov asked everyone he could stop, and could not get an answer from anyone.Finally, grabbing the soldier by the collar, he forced him to answer himself.

- Eh! Brother! Everyone has been there for a long time, they ran away! - the soldier said to Rostov, laughing at something and breaking free.

Leaving this soldier, who was obviously drunk, Rostov stopped the horse of the orderly or the guard of an important person and began to question him. The orderly announced to Rostov that an hour ago the sovereign had been driven at full speed in a carriage along this very road, and that the sovereign was dangerously wounded.

“It can’t be,” said Rostov, “that’s right, someone else.”

“I saw it myself,” said the orderly with a self-confident grin. “It’s time for me to know the sovereign: it seems like how many times I’ve seen something like this in St. Petersburg.” A pale, very pale man sits in a carriage. As soon as the four blacks let loose, my fathers, he thundered past us: it’s time, it seems, to know both the royal horses and Ilya Ivanovich; It seems that the coachman does not ride with anyone else like the Tsar.

Rostov let his horse go and wanted to ride on. A wounded officer walking past turned to him.

-Who do you want? – asked the officer. - Commander-in-Chief? So he was killed by a cannonball, killed in the chest by our regiment.

“Not killed, wounded,” another officer corrected.

- Who? Kutuzov? - asked Rostov.

- Not Kutuzov, but whatever you call him - well, it’s all the same, there aren’t many alive left. Go over there, to that village, all the authorities have gathered there,” said this officer, pointing to the village of Gostieradek, and walked past.

Rostov rode at a pace, not knowing why or to whom he would go now. The Emperor is wounded, the battle is lost. It was impossible not to believe it now. Rostov drove in the direction that was shown to him and in which a tower and a church could be seen in the distance. What was his hurry? What could he now say to the sovereign or Kutuzov, even if they were alive and not wounded?

“Go this way, your honor, and here they will kill you,” the soldier shouted to him. - They'll kill you here!

- ABOUT! what are you saying! said another. -Where will he go? It's closer here.

Rostov thought about it and drove exactly in the direction where he was told that he would be killed.

“Now it doesn’t matter: if the sovereign is wounded, should I really take care of myself?” he thought. He entered the area where most of the people fleeing from Pratsen died. The French had not yet occupied this place, and the Russians, those who were alive or wounded, had long abandoned it. On the field, like heaps of good arable land, lay ten people, fifteen killed and wounded on every tithe of space. The wounded crawled down in twos and threes together, and one could hear their unpleasant, sometimes feigned, as it seemed to Rostov, screams and moans. Rostov started to trot his horse so as not to see all these suffering people, and he became scared. He feared not for his life, but for the courage that he needed and which, he knew, would not withstand the sight of these unfortunates.

The French, who stopped shooting at this field strewn with the dead and wounded, because there was no one alive on it, saw the adjutant riding along it, aimed a gun at him and threw several cannonballs. The feeling of these whistling, terrible sounds and the surrounding dead people merged for Rostov into one impression of horror and self-pity. He remembered his mother's last letter. “What would she feel,” he thought, “if she saw me now here, on this field and with guns pointed at me.”

In the village of Gostieradeke there were, although confused, but in greater order, Russian troops marching away from the battlefield. The French cannonballs could no longer reach here, and the sounds of firing seemed distant. Here everyone already saw clearly and said that the battle was lost. To whomever Rostov turned, no one could tell him where the sovereign was, or where Kutuzov was. Some said that the rumor about the sovereign’s wound was true, others said that it was not, and explained this false rumor that had spread by the fact that, indeed, the pale and frightened Chief Marshal Count Tolstoy galloped back from the battlefield in the sovereign’s carriage, who rode out with others in the emperor’s retinue on the battlefield. One officer told Rostov that beyond the village, to the left, he saw someone from the higher authorities, and Rostov went there, no longer hoping to find anyone, but only to clear his conscience before himself. Having traveled about three miles and having passed the last Russian troops, near a vegetable garden dug in by a ditch, Rostov saw two horsemen standing opposite the ditch. One, with a white plume on his hat, seemed familiar to Rostov for some reason; another, unfamiliar rider, on a beautiful red horse (this horse seemed familiar to Rostov) rode up to the ditch, pushed the horse with his spurs and, releasing the reins, easily jumped over the ditch in the garden. Only the earth crumbled from the embankment from the horse’s hind hooves. Turning his horse sharply, he again jumped back over the ditch and respectfully addressed the rider with the white plume, apparently inviting him to do the same. The horseman, whose figure seemed familiar to Rostov and for some reason involuntarily attracted his attention, made a negative gesture with his head and hand, and by this gesture Rostov instantly recognized his lamented, adored sovereign.

“But it couldn’t be him, alone in the middle of this empty field,” thought Rostov. At this time, Alexander turned his head, and Rostov saw his favorite features so vividly etched in his memory. The Emperor was pale, his cheeks were sunken and his eyes sunken; but there was even more charm and meekness in his features. Rostov was happy, convinced that the rumor about the sovereign’s wound was unfair. He was happy that he saw him. He knew that he could, even had to, directly turn to him and convey what he was ordered to convey from Dolgorukov.

But just as a young man in love trembles and faints, not daring to say what he dreams of at night, and looks around in fear, looking for help or the possibility of delay and escape, when the desired moment has come and he stands alone with her, so Rostov now, having achieved that , what he wanted more than anything in the world, did not know how to approach the sovereign, and thousands of reasons presented themselves to him why this was inconvenient, indecent and impossible.

"How! I seem to be glad to take advantage of the fact that he is alone and despondent. An unknown face may seem unpleasant and difficult to him at this moment of sadness; Then what can I tell him now, when just looking at him my heart skips a beat and my mouth goes dry?” Not one of those countless speeches that he, addressing the sovereign, composed in his imagination, came to his mind now. Those speeches were for the most part held under completely different conditions, they were spoken for the most part at the moment of victories and triumphs and mainly on his deathbed from his wounds, while the sovereign thanked him for his heroic deeds, and he, dying, expressed his love confirmed in fact my.

“Then why should I ask the sovereign about his orders to the right flank, when it is already 4 o’clock in the evening and the battle is lost? No, I definitely shouldn’t approach him. Shouldn't disturb his reverie. It’s better to die a thousand times than to receive a bad look from him, a bad opinion,” Rostov decided and with sadness and despair in his heart he drove away, constantly looking back at the sovereign, who was still standing in the same position of indecision.

While Rostov was making these considerations and sadly driving away from the sovereign, Captain von Toll accidentally drove into the same place and, seeing the sovereign, drove straight up to him, offered him his services and helped him cross the ditch on foot. The Emperor, wanting to rest and feeling unwell, sat down under an apple tree, and Tol stopped next to him. From afar, Rostov saw with envy and remorse how von Tol spoke to the sovereign for a long time and with fervor, and how the sovereign, apparently crying, closed his eyes with his hand and shook hands with Tol.

“And I could be in his place?” Rostov thought to himself and, barely holding back tears of regret for the fate of the sovereign, in complete despair he drove on, not knowing where and why he was going now.

His despair was the greater because he felt that his own weakness was the cause of his grief.

He could... not only could, but he had to drive up to the sovereign. And this was the only opportunity to show the sovereign his devotion. And he didn’t use it... “What have I done?” he thought. And he turned his horse and galloped back to the place where he had seen the emperor; but there was no one behind the ditch anymore. Only carts and carriages were driving. From one furman, Rostov learned that the Kutuzov headquarters was located nearby in the village where the convoys were going. Rostov went after them.

The guard Kutuzov walked ahead of him, leading horses in blankets. Behind the bereytor there was a cart, and behind the cart walked an old servant, in a cap, a sheepskin coat and with bowed legs.

- Titus, oh Titus! - said the bereitor.

- What? - the old man answered absentmindedly.

- Titus! Go threshing.

- Eh, fool, ugh! – the old man said, spitting angrily. Some time passed in silent movement, and the same joke was repeated again.

At five o'clock in the evening the battle was lost at all points. More than a hundred guns were already in the hands of the French.

Przhebyshevsky and his corps laid down their weapons. Other columns, having lost about half of the people, retreated in frustrated, mixed crowds.

The remnants of the troops of Lanzheron and Dokhturov, mingled, crowded around the ponds on the dams and banks near the village of Augesta.

At 6 o'clock, only at the Augesta dam, the hot cannonade of some Frenchmen could still be heard, who had built numerous batteries on the descent of the Pratsen Heights and were hitting our retreating troops.

In the rearguard, Dokhturov and others, gathering battalions, fired back at the French cavalry that was pursuing ours. It was starting to get dark. On the narrow dam of Augest, on which for so many years the old miller sat peacefully in a cap with fishing rods, while his grandson, rolling up his shirt sleeves, was sorting out silver quivering fish in a watering can; on this dam, along which for so many years the Moravians drove peacefully on their twin carts loaded with wheat, in shaggy hats and blue jackets and, dusted with flour, with white carts leaving along the same dam - on this narrow dam now between wagons and cannons, under the horses and between the wheels crowded people disfigured by the fear of death, crushing each other, dying, walking over the dying and killing each other only so that, after walking a few steps, to be sure. also killed.

Every ten seconds, pumping up the air, a cannonball splashed or a grenade exploded in the middle of this dense crowd, killing and sprinkling blood on those who stood close. Dolokhov, wounded in the arm, on foot with a dozen soldiers of his company (he was already an officer) and his regimental commander, on horseback, represented the remnants of the entire regiment. Drawn by the crowd, they pressed into the entrance to the dam and, pressed on all sides, stopped because a horse in front fell under a cannon, and the crowd was pulling it out. One cannonball killed someone behind them, the other hit in front and splashed Dolokhov’s blood. The crowd moved desperately, shrank, moved a few steps and stopped again.

Mongols continue to suffer from changes in writing system

After the introduction of the politically imposed Cyrillic alphabet, Mongols are confused between the horizontal and vertical writing systems

This summer I went on an expedition along the route Beijing - Inner Mongolia - Manchuria - the center of Russian Buryatia Ulan-Ude - Ulaanbaatar - Beijing.

I processed almost all the collected materials on the spot, but I wanted to take the most important ones with me - they did not fit into my luggage, and I had to carry several folders with me.

Mongols who have difficulty understanding the Mongolian alphabet

Usually I take a train between Ulan-Ude and Ulaanbaatar, but this time the travel time was limited and I crossed the border by bus, which took me 12 hours to my destination.

This circumstance in itself was not a tragedy, and I don’t even need to write about the terrible quality of the road; the shaking when you drive along it causes nausea on both the Russian and Mongolian sides.

However, after we crossed the border, one person got on the bus. As I learned later, checkpoint employees or members of their families usually sit after the border.

The bus was almost full, but there were a few empty seats in the back, one of which was next to me. This young Mongol sat down next to me. As I found out from a subsequent conversation, he worked at the border at passport control, and was traveling to Ulaanbaatar to take exams for promotion. First he spoke to me in English, and I noticed his excellent pronunciation.

He was leafing through books bought in Russia, or perhaps magazines from his pocket in the bus seat, and suddenly began to read a text he found in one of the books, written vertically.

He had difficulty making his way through the vague meaning of the column of letters, but in the end he said that, apparently, we were talking about war (I was just feeling nauseous, so I was not able to read).

He explained that he studied these letters at school, but due to lack of habit, he could only read what was written syllable by syllable. The text was written in Mongolian letters.

Now in the Mongolian language there are two types of writing. The first is a vertical type using the Mongolian alphabet, the second is a horizontal letter in Cyrillic, as in Russian.

The Mongolian alphabet is used throughout Chinese Inner Mongolia, while the Cyrillic alphabet is used in Mongolia itself. Due to the fact that Mongolia writes in Cyrillic, they are often asked whether the Mongolian language is similar to Russian, while in fact it is close in grammar to Japanese.

Mongolian is very similar to Japanese

After the two or three years I spent in Mongolia, my Japanese became a little strange.

One of the reasons for the slight deviations was that it was enough to substitute Mongolian words for Japanese words, including grammatical indicators, in order to communicate with people around them - the Mongolian language is so close to Japanese. Because of this, over the course of two or three years, I began to think more in Mongolian, and my Japanese began to sound strange.

The Mongolian language switched to Cyrillic in 1946. It is believed that the Mongolian alphabet originates in the 12th-13th centuries. Mongolian letters were introduced with the help of the Uyghurs, who in turn took them from the horizontal Arabic script.

The Mongols themselves cite the convenience of this method of writing for a rider on a horse as the reason that the horizontal writing system turned into a vertical one. Scientists suggest that they probably came to the vertical script in the process of signing trade agreements with China, where Mongolian was assigned next to the vertical Chinese script.

In addition, under the inscriptions of the names of the gates in the Chinese Forbidden City there are still signatures in the Manchu language, which used the Mongolian alphabet.

The Mongolian language has tried more than one script - either because the Mongolian script was borrowed from the Uyghurs, or because it could not fully reflect the sounds of the language.

Among other things, the Mongols used a square alphabet created by the Tibetan Buddhist monk Pagba Lama, which they sought to develop into an international script for recording the languages of the small peoples ruled by the Yuan dynasty. The Yuan Dynasty was eventually overthrown in 1368, and the Mongols fled to the Mongolian plateau and then stopped using the Pagba script.

The reason for such a rapid abandonment of the square script was that the Pagba script was more difficult to write than the Mongolian alphabet, which had a cursive variant. Due to the fact that the Mongolian alphabet could not accurately convey sounds, it was equally far from all dialects, and the Pagba letter, on the contrary, accurately reflected all the phonetic features of the court Mongolian language, but was too far removed from the dialects.

Moreover, there is even a theory that the Korean Hangul alphabet was not created from scratch, but arose under the influence of the Pagba script.

600 years after those events, the moment of truth has come for the Mongolian alphabet, which has endured numerous trials. A revolution took place in 1921, and socialist power was established in 1924.

Switch from Latin to Cyrillic under influence of the Soviet Union

Considering that the Mongolian alphabet is the reason for the low (less than 10%) literacy rate of the population, the authorities announced that the Mongolian language would be written in a “revolutionary way” - in the Latin alphabet.

Of course, it was simply necessary to teach people the Mongolian alphabet, using, for example, traditional Buddhist texts. Probably one of the reasons for the replacement was the fear that if nothing was changed, the “new socialist thinking” would never take root.

In the early 1930s, the Latin alphabet was introduced, with the opposition, which supported the Mongolian writing style, winning a temporary victory. However, in the second half of the 1930s, sentiment changed dramatically after Stalin's wave of terror and accusations of nationalist use of the Mongolian alphabet.

In order to save their lives, everyone was forced to support the transition to the Latin alphabet.

In February 1941, the authorities gave the green light to use the Latin alphabet, but a month later they approved the Cyrillic alphabet as the official writing system. The decision was made by the same composition that approved the Latin alphabet.

It is obvious that pressure was exerted from Moscow, the center of the revolution.

Even in Chinese Inner Mongolia in the 1950s, there was a movement to introduce the Cyrillic alphabet. However, it immediately stopped as soon as the shadow of the Soviet-Chinese confrontation, which emerged from the late 1950s, fell on the movement.

During perestroika in the second half of the 1980s, the center's grip loosened, and a movement to restore folk traditions emerged in Mongolia (then the Mongolian People's Republic).

The Mongolian alphabet has become a symbol of national traditions. There were calls to abandon the Cyrillic alphabet and restore the Mongolian alphabet. In September 1992, first graders began learning Mongolian letters.

However, when these children entered the third grade, they were again transferred to the Cyrillic alphabet. The reason was that numbers and chemical formulas did not fit with vertical writing, and, most importantly, in the conditions of a terrible economic situation there was no money either for textbooks or for training teaching staff who would teach science using vertical writing.

Divided by border, Mongols continue to use different scripts

Thus, a situation has arisen where Mongols in Mongolia and Mongols in Chinese Inner Mongolia speak the same language but write differently. Most likely, the situation will remain this way.

Differences in similar languages separated by a border line can be seen in many different places around the world. One example may be the emergence of new languages after a country gained political and linguistic independence from its former metropolis.

This perception is especially strong in countries bordering each other. Similar phenomena could be observed in Norway when it separated from Denmark, in the case of Spain and Portugal, Serbia and Croatia.

However, it is important that in Mongolia and Inner Mongolia the phenomenon of divergence in writing options is not the result of differences between peoples, but the result of policies imposed by another state.

If we recall the Buryats, who also previously used the Mongolian alphabet and had close contact with Mongolia (in 1938, the Cyrillic alphabet, which differed from the Mongolian language, was established as the main script for them), then the problem of separation by borders becomes clear.

Among the countries of Central Asia that gained their independence from the USSR, there were also those that switched to the Latin alphabet in order to escape the sphere of influence of Russia.

Initially, in the 1920-1930s, the languages of the Central Asian countries adopted the Latin alphabet as their written language. This transition was the result of the modernization movement that began in the mid-19th century. In 1928, Türkiye adopted the Latin script for the Turkish language, which became one of the examples of general trends in Central Asian countries.

Even in Russia itself, the movement for the adoption of Latin writing for the Tatar language gained strength. When the countdown to the introduction of the Latin alphabet began in December 2002, amendments to the law on the national languages of small nationalities of the Russian Federation were adopted, which limited the writing of the federal language and the languages of the republics of small nationalities within the Russian Federation to Cyrillic only. The movement for change stopped there.

These events can be linked to the use of writing to indicate spheres of influence. You can also call this the fate of small nations.

If you think about it, the Latin, Cyrillic, Arabic, Indian Devanagari or Chinese characters denote a certain cultural circle, and sometimes a religious sphere of influence. In some cases, as with the Pagba script, the script disappears with the collapse of the empire and the destruction of its sphere of influence. It turns out that the issue of writing is quite politicized.

Meanwhile, a young Mongolian is having difficulty deciphering Mongolian symbols. His appearance gave me something to think about.

A review of Mongolian writing, including the one that Mongolia is trying to return, in our review.

In an illustration from the website of the Russian edition of Radio “Voice of Mongolia”:

This is what the old Mongolian script looks like.

“On the eve of the 100th anniversary of the National Liberation Revolution of 1911, the President of Mongolia issued a decree to expand the official use of the Old Mongolian script in order to accelerate the implementation of state policy to restore the national script.

According to the decree, official letters from the President, the Chairman of the Parliament, the Prime Minister and members of the government of Mongolia, addressed to persons at relevant levels of foreign states, must be drawn up in the national script, and must be accompanied by translations into one of the official languages of the UN or into the language of the country -recipient.

“Birth certificates, marriage certificates and all educational documents issued by educational institutions at all levels must be written in both Cyrillic and Old Mongolian script,” the decree states. The President also gave directives to the government to accelerate the progress of the “National Program for the Dissemination of Mongolian Writing-2”, approved in 2008. The decree came into force on July 11, 2011,” reported Mnogolya Foreign Broadcasting. End of quote.

About Old Mongolian writing

Let's talk about old Mongolian writing. The Old Mongolian script was abolished in Mongolia in 1941, after the transition to the Cyrillic alphabet, before which the country briefly switched to the Latin alphabet.

The Old Mongolian classical script was developed at the behest of Genghis Khan, according to legend, by a captive Uyghur scribe precisely on the basis of the Uyghur script (which has roots in the Sogdian and Aramaic alphabets).

Note that the Sogdians are representatives of the disappeared Eastern Iranian people, who, having mixed with the Persian tribes, became the ancestors of the modern Tajiks. (In Tajikistan, the name of the Sogd region reminds of the Sogdians). Sogdian writing was based on the Aramaic alphabet - script from right to left. Aramaic, in turn, was spoken by many Semitic peoples. By the way, Aramaic is the language of Christ. Now Kurdish languages are close to Aramaic.

And the Uyghur Turkic people, who also took part in the creation of the Mongolian classical writing, now known as Old Mongolian, still live in what is now China.

Features of Old Mongolian writing

Genghis Khan demanded from the Uyghur scribe that the new writing reflect the most archaic form of the language, in order to unite the speakers of various dialects and strengthen the unity of the Mongol tribes.

Old Mongolian script is vertical (columns go from left to right). Verticality is believed to be due to the influence of Chinese writing on the Uighurs and Sogdians, since archaeological scientists have discovered shards and other variants of writing signs, but in the course of the historical process, vertical recording has won.

Mongolian language and writing. From history

In the Mongolian languagePerii was a variety of Mongolian that is now known as Middle Mongolian.

However, later in the states that were formed under the control of Genghis Khan’s relatives in different parts of Eurasia and at first still recognized the power of the main khan - the so-called. Great Khan, Mongolian was no longer the main language.

In the Golden Horde (a state that arose as an ulus of Genghis Khan's eldest son Jochi, it adjoined the Russian principalities, which were under his vassalage), Kipchak, now extinct, belonged to the Turkic family of languages).

In the state of the Ilkhans, founded by the grandson of Genghis Khan Hulagu and located in the Middle East (present-day Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Central Asia), Persian became the official language along with the Central Mongolian.

In China, where the Mongols founded the Yuan Dynasty ("new beginning"), the rulers adopted the Chinese language, to its former main capital.

In Mongolia itself, which had ceased to be a world power, the Mongolian language, now known as Khalkha Mongol, from the dominant Mongol group in the territory (lit. "shield") continued to be spoken.

Mongolian writing changed quite dramatically several times:

Old Mongolian script developed in 1204, created at the behest of Genghis Khan based on the Uyghur alphabet, as discussed above.

In 1269, the square letter Pagba Lama appeared based on Tibetan symbols, created by order of the Great Khan, founder of the Yuan dynasty, Kublai Kublai, to better reflect Chinese words V. Classical Mongolian writing was not suitable for recording languages with a different phonology from Mongolian, in particular Chinese. Therefore, when the Mongol rulers conquered China, Kublai Khan ordered the creation of a new script, called the “square Mongol script,” which went out of circulation after the expulsion of the Mongol rulers from China

In 1648, based on the old Mongolian letter, the Buddhist monk Zaya-Pandit developed its improvement - todo-bichig (i.e. “clear letter”). "Todo bichig" was created to better reflect the pronunciation in writing.

In 1686, the ruler of Mongolia, Zanabazar, created something new - a graphic variation based on Indian symbols, called the Soyombo script. The first Mongolian Bogdo-gegen Dzanabadzar, a spiritual and secular ruler who already ruled the remnants of the Mongol empire, in order to better convey Tibetan and Sanskrit words, and the Mongols from shamanists became Tibetan Buddhists, created the Soyombo writing based on Indian characters, the first - where the letters were not written vertically , but horizontally. The font symbol is the national emblem of Mongolia, depicted on the flag and coat of arms.

The Eastern heritage was rejected in 1941, when Mongolia switched to Latin writing, which already in 1943, on orders from Moscow, was replaced by the more ideologically correct Cyrillic alphabet.

Naturally, the Cyrillic alphabet and, to some extent, the Old Mongolian alphabet can be called more or less commonly used in modern Mongolia.

The newspaper “Humuun Bichig” is now published in the Old Mongolian script, the only one in the country published in the Old Mongolian script. Old Mongolian writing also began to be taught in schools.

Nowadays in the Republic of Mongolia there is a very slow, almost imperceptible process of transition from the Cyrillic alphabet to the Old Mongolian alphabet. Interestingly, the Mongols of the Chinese region of Inner Mongolia officially retained a script based on Old Mongolian, although they suffer from the dominance of the Chinese language. (By the way, the Mongols of Inner Mongolia are the majority of the Mongols in the world. Of the approximately 8-10 million Mongols in the world, only 2.5 million live in independent Mongolia, and more than 6 million in China., incl. 4th million in Inner Mongolia).