The Greeks appeared on the shores of the Northern Black Sea region as a result of the Great Greek colonization in the middle of the 7th century. BC Most of their settlements were founded between the 6th and 4th centuries. BC Their existence and vital activity contributed to the collapse of tribal relations and the transition to the civilization of the Scythians and other peoples of the region. From that time on, city life began here, continuing to the present day (Pantikapaeus-Kerch, Feodosia, Chersonesus-Sevastopol). During the Middle Ages, some of the Greek settlements became ancient Russian cities and played a significant role in the history of Ancient Rus'.

The Greeks who moved to the Northern Black Sea region brought with them a new type of social structure - the polis, a civil collective of small landowners and warriors. The center of the polis was usually a walled city. However, in the Northern Black Sea region at the early stage of their history, Greek settlements did not have fortifications, since the local population here at that time was small (the Cimmerians went to Asia, and the Scythians soon followed them) and did not interfere with the settlement of the Greeks. The main areas of Greek colonization were the mouth of the Southern Bug, where the city of Olbia arose, the region of the Kerch and Taman peninsulas, where in the 5th century. BC The Bosporan kingdom or Bosporus was formed, and the region of southwestern Crimea, where the polis of Chersonesus arose.

The agricultural district of cities was called chora. On the choir there were land plots of citizens, most of whom were farmers in the early period of colonization. Agriculture was arable. Cattle were used for plowing. They grew naked wheat (the local population produced mainly chaffy varieties of wheat, not suitable for export), rye, barley, millet and other crops. The lands here were fertile and the harvests were so significant that part of the production was exported to the cities of Greece and Asia Minor in exchange for traditional Greek clothing, handicrafts and such national Greek food products as wine and olive oil. According to the Athenian orator Demosthenes in the 4th century. BC The cities of the Bosporus state supplied Athens with half of the bread the city needed. In the cities and rural settlements of the Northern Black Sea region, numerous agricultural tools are found (iron openers, hoes, grain grinders, and later millstones); there are their images on coins and in the painting of Greek vases. The development of agriculture is also evidenced by the numerous grain pits discovered in all Greek settlements.

As settlements grow, gardening, viticulture and their own winemaking also develop. In many Black Sea cities there are special architectural structures - wineries, designed to produce several thousand liters of wine (Fig. 2). Small rural settlements appeared around the cities; they were especially numerous on the Kerch and Taman peninsulas as part of the Bosporan kingdom.

In addition to agriculture, cattle breeding is also undergoing significant development. In addition to the already mentioned cattle, the Greeks raised goats, sheep, pigs, horses, and poultry. Wool and skins of domestic animals were used in weaving and leather crafts, and milk and meat were used for food.

One of the favorite types of food among the ancient Greeks was fish. Fishing occupied second place in their economy after agriculture. In all cities and even relatively small ancient settlements there are special baths for salting fish, the walls of which are coated with tsemyanka (finely crushed ceramics) (Fig. 3). The capacity of some of them is so large that it is quite obvious that they are producing salted fish for sale. Salt for this was mined in saltworks at the mouth of the Dnieper, on salt lakes near Chersonesus and on the Bosporus. In addition, in cities and settlements there are always numerous clay and stone sinkers for nets, fish hooks, fish bones and scales, and mussel shells. Judging by the finds, in the early period the Greeks caught mainly sturgeon fish; later, finds of bonito, anchovy, and sultana became more numerous in their settlements.

By the 4th century. BC Some of the colonies turned into large urban centers surrounded by powerful walls and towers. In cities, street layouts take shape. The most elevated part of them is occupied by temples and houses of the nobility. The streets are paved with cobblestones, with drains and sewer channels running underneath them.

By the 4th century. BC Some of the colonies turned into large urban centers surrounded by powerful walls and towers. In cities, street layouts take shape. The most elevated part of them is occupied by temples and houses of the nobility. The streets are paved with cobblestones, with drains and sewer channels running underneath them.

The central square, the agora, becomes the public and commercial center of the city. Public buildings are usually concentrated around it (prytanei - buildings for meetings of the executive branch, dicasteries - courts, gymnasiums - philosophical and sports schools, etc.). One of the most important public buildings in Greek cities has always been the theater. The remains of theaters are open in Chersonesus (Fig. 4) and Olbia. Rice. 4

The central square, the agora, becomes the public and commercial center of the city. Public buildings are usually concentrated around it (prytanei - buildings for meetings of the executive branch, dicasteries - courts, gymnasiums - philosophical and sports schools, etc.). One of the most important public buildings in Greek cities has always been the theater. The remains of theaters are open in Chersonesus (Fig. 4) and Olbia. Rice. 4

According to written evidence, there were theaters in all cities of the Bosporus. In almost all Black Sea cities there are finds of various theatrical props: bone and ceramic entrance tickets (tesserae), theatrical masks, fragments of theater seats, terracotta figurines of actors, etc.

The temples built in the Black Sea region completely repeated the forms of the temples of their metropolises. For their interior decoration, Crimean and Caucasian marble of pinkish and gray color with veins was used. The inside walls of temples and other public buildings were plastered and painted. Antique plaster was of such high quality that its fragments, found by archaeologists, look great and are preserved in modern conditions, although they have lain in the ground for more than 2000 years. The painting of the walls of residential buildings and public buildings usually consisted of several horizontal belts, painted in different colors or reproducing some kind of geometric pattern. Red was a particularly favorite color. Some fragments of plaster were painted to resemble marble. The painters reproduced architectural details, as if talking about the structures of the walls. Earth paints were used and applied using the fresco technique on wet plaster with preliminary scratching of the contours. Only fragments remain of the colorful paintings of residential buildings. Temples stood out sharply against the background of residential buildings, decorating the cities.

Unlike local settlements and small rural settlements, almost every Greek city had a system of plumbing facilities. They were usually made from ceramic pipes or lined with stone tiles. It is also known that there were fountains, pools and baths in cities. All this indicates a high level of hygiene

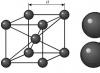

The living quarters of the early settlers were built in the form of half-dugouts and dugouts, but already from the 5th century. BC Greeks everywhere switched to stone (on the Taman Peninsula to adobe or adobe-stone) house-building. Walls were usually built without a binder mortar. The walls facing the street had no windows. The roof was covered with ceramic tiles (Fig. 5). Inside the house there was an open courtyard paved with stone tiles or

The living quarters of the early settlers were built in the form of half-dugouts and dugouts, but already from the 5th century. BC Greeks everywhere switched to stone (on the Taman Peninsula to adobe or adobe-stone) house-building. Walls were usually built without a binder mortar. The walls facing the street had no windows. The roof was covered with ceramic tiles (Fig. 5). Inside the house there was an open courtyard paved with stone tiles or

Rice. 5 colored pebbles.

The doors of the residential and utility premises opened onto the courtyard and through the courtyard they went out onto the street. In residential areas of the Black Sea region, round or rectangular fireplaces are common. Finds of fragments of portable braziers show that other areas of the dwellings were also heated, since the climate here was more severe than in Greece. Most of the Bosporan houses are small and quite modest. Usually only the foundations were preserved from them.

The doors of the residential and utility premises opened onto the courtyard and through the courtyard they went out onto the street. In residential areas of the Black Sea region, round or rectangular fireplaces are common. Finds of fragments of portable braziers show that other areas of the dwellings were also heated, since the climate here was more severe than in Greece. Most of the Bosporan houses are small and quite modest. Usually only the foundations were preserved from them.

Rice. 6 Decorative sculpture and relief played a significant role in the design of the external appearance of the Greek cities of the Black Sea region. A remarkable marble statue of a sphinx or griffin (5th century BC) comes from Olbia. One of the squares of the Bosporan city of Phanagoria in the 3rd century. BC decorated with a limestone relief depicting a griffin (Fig. 6).

In Panticapaeum there were paired statues of a man and a woman, well conveying the appearance of the inhabitants of that time (Fig. 7). There are also sculptural motifs in the decoration of altars, fountains, marble sundials (Fig. 8), on the slabs of city decrees, resolutions and honorary inscriptions.

ABOUT  The main type of funeral rite of the Greek settlers was inhumation in rectangular ground pits. But cremation also occurs. The composition of the grave goods clearly shows social differentiation: there are very rich, average and poor burials. In the poor, the deceased was usually buried with one or two vessels, the rest of the inventory was made up of parts

The main type of funeral rite of the Greek settlers was inhumation in rectangular ground pits. But cremation also occurs. The composition of the grave goods clearly shows social differentiation: there are very rich, average and poor burials. In the poor, the deceased was usually buried with one or two vessels, the rest of the inventory was made up of parts

Rice. 8 clothes. In medium and especially rich burials, as a rule, they were buried in wooden or stone sarcophagi with a large amount of dishes, decorations, and occasionally weapons. Stone sarcophagi often copied the shape of a Greek house or temple. This similarity reflects ideas about the glorification of the dead. The proximity to the Scythians led to the fact that representatives of the nobility began to build large stone crypts, over which mounds were poured. The largest number of such burials have been discovered near the capital of the Bosporus, Panticapaeum. The most striking monument here is the Royal Mound (Fig. 9).

P  It is believed that one of the most powerful Bosporan rulers was buried in it. The crypt of the mound consisted of a dromos, covered with a horizontal stepped vault, and a burial chamber, square in plan, but covered with a circular stepped vault. The date of construction of the crypt is the middle of the 4th century. BC It is interesting that in the initial period of the spread of Christianity in the Bosporus, the crypt of the mound was turned into a secret Christian chapel and Christian symbols - crosses - were carved on its walls.

It is believed that one of the most powerful Bosporan rulers was buried in it. The crypt of the mound consisted of a dromos, covered with a horizontal stepped vault, and a burial chamber, square in plan, but covered with a circular stepped vault. The date of construction of the crypt is the middle of the 4th century. BC It is interesting that in the initial period of the spread of Christianity in the Bosporus, the crypt of the mound was turned into a secret Christian chapel and Christian symbols - crosses - were carved on its walls.

Many of the burial crypts had paintings. Thus, in the Bolshaya Bliznitsa mound near ancient Phanagoria, a crypt of the 4th century was discovered. BC with a picturesque image of the goddess

agriculture of Demeter. In the first centuries AD. crypts began to be carved into mainland clay or rock and also covered with fresco painting. Of the paintings with mythological content, the most interesting are the frescoes of the crypt of Demeter in Kerch. They date back to the 1st century. AD The crypt is named after the main image - in the center of the semi-cylindrical vault in a round medallion on a deep blue background there is a chest-length image of the goddess of agriculture Demeter (Fig. 10). The face with huge eyes is full of deep sadness and it seems that she looks straight into the eyes of the person who enters the crypt, no matter where he stands. The artist achieved stunning expressiveness of this face, which, once seen, is impossible to forget.

On the wall opposite the entrance to the chamber there is a scene of the abduction of Demeter's daughter Cora by the god of the underworld Pluto. On both sides of the entrance are images of the gods Hermes and Calypso, accompanying the souls of the dead to the afterlife. All free space on the walls and ceiling is filled with images of leaves, flowers, grapes and birds. The painting as a whole is distinguished by the harmonious unity of all parts, which is characteristic of the canons of ancient art.

In paintings on real themes we can learn a lot about the everyday situation and living conditions of the Bosporans. The 1st century crypt is typical in this regard. AD, where a certain Anthesterius was buried (Fig. 11). The painting on the walls depicts a felt yurt, a woman and children sitting near it, and armed horsemen in nomadic clothes galloping towards the tent. On the left is a tree with a quiver hanging on it; a long spear rests against the tree. All figures are placed freely, but at the same time connected into a single whole. It is quite obvious that the artist conveyed a picture of local real life, and this picture testifies to the significant impact of barbaric cultural elements on the life of the Bosporans.

N  Less interesting are the images of the Stasovsky crypt, so named

Less interesting are the images of the Stasovsky crypt, so named

named after the remarkable Russian critic V.V. Stasov, who first explored this crypt. Here, against the background of plant motifs, scenes of the battle between the Bosporans and the Sarmatians, birds and animals are depicted (Fig. 12). The painter managed to convey the swiftness of movement, the combatants and the drama of the battle.

R  is. 12

is. 12

The details of clothing and weapons are accurately depicted. The walls of the crypt also have paintings. The details of clothing and weapons are accurately depicted. The walls of the crypt also have paintings.

Of the recent most significant finds of Bosporan painting, the most significant is the crypt of Hercules, discovered in Anapa in 1975. It dates back to the beginning of the 3rd century. AD and is the only source known to date that conveys all 12 labors of Hercules. Here the techniques of late painting are already clearly visible - the rendering of folds of clothing in parallel thick lines, the continuous filling of the mass of hair, the graphic depiction of the body of Hercules. Particularly successful is the rendering of the movement and angles of the body of Hercules killing the Stymphalian birds (Fig. 13).

Artistically, the Panticapaean paintings of the Roman era are a combination of realistic and conventionally schematic features. The artists sought to fully and colorfully reproduce the external environment, but in the staging of the figures and the interpretation of movement, tendencies of conventionality, flatness and schematism are clearly visible. This is explained by the interaction of ancient, Asia Minor, Roman and local Scythian-Sarmatian cultures, which have their own artistic traditions.

All Greek cities had developed handicraft production. Let us note right away that none of the other peripheral areas of the spread of ancient culture can compare with the Northern Black Sea region in terms of the abundance and diversity of metal products that have reached us. This is especially true for products made of precious metals. World famous products originating from here

All Greek cities had developed handicraft production. Let us note right away that none of the other peripheral areas of the spread of ancient culture can compare with the Northern Black Sea region in terms of the abundance and diversity of metal products that have reached us. This is especially true for products made of precious metals. World famous products originating from here

Jewelry art (toreutics) made of gold, silver, electrum (an alloy of gold and silver) came to us mainly due to the fact that they were included in the funerary inventory of the burials of the nobility of ancient cities and neighboring tribes. Greek masters of the 4th-3rd centuries. BC, most of whom, according to experts, worked in Panticapaeum with great technical skill, making things from gold, using the technique of chasing, filigree and a small amount of blue and green enamel. The organization of large-scale production in Panticapaeum, however, did not exclude the import of toreutics products from Greece and the activity of small workshops in other cities of the Bosporus. There was its own jewelry production, albeit on a smaller scale, in both Olbia and Chersonesus. The most important for the history and culture of the ancient world are women's gold earrings from Feodosia, rightfully considered one of the most famous examples of Greek microtechnology (Table 15.1), a large gold pendant found in the Kul-Oba mound near Kerch with a relief image of the head of a goddess Athens (Table 15.2) and a diadem from the Artyukhovsky mound with pendants and a knot made of large garnets, processed in the shape of a cord (Table 15. 3). Most of the best items made of gold and silver from the Bosporus were found during excavations of Scythian burial mounds.

In all cities there are remains of workshops that made tools from iron and bronze. In Panticapaeum, the remains of a large workshop where weapons were produced were also discovered. It is curious that such weapons as arrowheads were all made according to Scythian forms, which indicates the complete adoption of this type of weapon by the Bosporans.

Ceramic production was also highly developed in the cities of the Black Sea region. Potters' quarters are open in almost all major centers. Pottery was made on a potter's wheel. The shapes of Greek vessels are varied and very numerous (Table 16). The most common find in all Greek settlements are fragments of amphoras, two-handled narrow-necked vessels with a sharp bottom, intended for transporting wine, grain, olive oil, wool, paints, nuts, etc. The capacity of amphoras of different centers was different. The handles and necks of amphorae were often marked with the marks of potters or city officials who controlled the release of containers. In addition to containers, there were also painted (Panathenaic) ceremonial amphorae, which were awarded to the winners of sports competitions. Their painting corresponded to the type of competition (Table 15.4).

To store grain and wine, the Greeks used large clay barrels - pithos, which were buried in the ground in the courtyards of residential buildings. The pithos could be so large that a person could easily fit in it. In particular, ancient tradition reports that it was in pithos that the philosopher Diogenes lived.

Tableware, as a rule, was painted. In the early period, black varnish was used for this, which artists used to paint figures. This style of painting is called black-figure. Later, they began to fill only the space around the figures with black varnish and complement the elements of the face and clothing, while the figures themselves were left in the color of baked clay. This type of painting is called red-figure painting. Red-figure vessels represent the pinnacle of Greek ceramic painting. One of the most interesting antique vases of this type is the “pelik with a swallow” by master Euphronius (Fig. 14) from the collection of the State Hermitage. The front side of the vase depicts a living scene of Hellenic life. The characters presented on it gesticulate excitedly, as if complementing their words, which are also depicted by the artist. A young man sitting on a stool on the left, pointing to a swallow flying in the sky, says: “Look, a swallow.” The man sitting opposite the young man, turning his upper body back and throwing his head back strongly, confirms “It’s true, I swear by Hercules.” A boy standing behind the man, raising his hands up, shouts in delight: “Here she is.” And this conversation ends with the man’s phrase: “It’s already spring.” The whole scene is drawn vividly and naturally.

In the 3rd century. BC In the Bosporus, the production of painted vases, conventionally called “watercolors,” became widespread. The images were painted on them with paints diluted with water. At the same time, the background, in imitation of the red-figure technique, was painted over with a dark color. The preservation of such paintings is often poor, but in the surviving drawings one can see interesting compositions with mythological and everyday scenes.

In the 3rd century. BC In the Bosporus, the production of painted vases, conventionally called “watercolors,” became widespread. The images were painted on them with paints diluted with water. At the same time, the background, in imitation of the red-figure technique, was painted over with a dark color. The preservation of such paintings is often poor, but in the surviving drawings one can see interesting compositions with mythological and everyday scenes.

In addition to ordinary types of dishes, the Hellenes also used shaped vessels of a wide variety of shapes in everyday life. Among them, vessels in the form of animal heads, the so-called rhytons, are often found.

But the clay bottles for fragrant oils found in ancient Phanagoria are especially famous. One of them depicts a sphinx, another - a siren (half-woman, half-bird), the third - the goddess of beauty Aphrodite in the open shell. The delicate pink and blue tones of well-preserved paint on them are harmoniously combined with gilding (Fig. 15).

In the III-I centuries. BC A new custom also appeared - not to paint the dishes, but to decorate them with relief patterns. Hemispherical bowls, decorated on the outside with complex floral, geometric or figured relief ornaments, are becoming widespread. These vessels were called “Megaran bowls” after the place of their first finds in the Greek city of Megara. But now it has been established that they were manufactured in many ancient cities, including in the Northern Black Sea region. Forms for the production of Megarians were found in Olbia and the Bosporus.

In the III-I centuries. BC A new custom also appeared - not to paint the dishes, but to decorate them with relief patterns. Hemispherical bowls, decorated on the outside with complex floral, geometric or figured relief ornaments, are becoming widespread. These vessels were called “Megaran bowls” after the place of their first finds in the Greek city of Megara. But now it has been established that they were manufactured in many ancient cities, including in the Northern Black Sea region. Forms for the production of Megarians were found in Olbia and the Bosporus.

bowls and fragments of vessels made in these forms (Table 15.5).

At the same time, dishes coated with red varnish appear. This varnish was practically the same in composition as black varnish, but the conditions for firing the dishes changed and it acquired a different color. Red-glazed dishes were preserved until the end of ancient history, but the forms and types of vessels in the first centuries AD. gradually change.

Despite the large amount of pottery ceramics of the most varied form and purpose, even in its heyday, the inhabitants of the Hellenic Black Sea cities could not do without ordinary, or, as it is also called “kitchen”, molded utensils. In all cities and rural settlements, archaeologists find vessels such as pots, frying pans, pots, mugs, lamps, in which the Hellenes cooked food or used them for other purposes. Usually such dishes were made by the owner himself or his wife.

In addition to tableware, ceramic production is known for the production of tiles and some architectural details that decorate houses, clay pipes for water pipes, heating systems, and plumbing purposes. Numerous cult and genre figurines were made from clay, usually called terracotta, spindle whorls and weights for looms, and much more (Table 18, 12-14).

Significantly fewer archaeological traces remain of such crafts as weaving, woodworking, leatherworking, stonemasonry, bone carving, and glassmaking. But all of them are represented by a fairly diverse assortment of products, which allows us to talk about the high standard of living of the population of the ancient cities of the Northern Black Sea region.

Developed own agriculture, handicraft production and crafts contributed to the vigorous development of trade between the Greeks and neighboring barbarian peoples and cities of Greece proper. They brought mainly agricultural and fishing products to Greece, and the barbarians were supplied with wine, fabrics, clothing, and handicraft products. Developed trade relations required the development of their own monetary economy. Along with the use of imported coins, residents of the Black Sea policies began to mint their own. Initially it was a small coin intended for circulation only on the domestic market. Large monetary units have been in circulation since the 4th century. BC Most often, patron deities of cities were depicted on their front side (obverse), and additional symbols and the name of the city in full or abbreviated form were depicted on the back (reverse) (Table 17, 1-11).

For the first time, Hellenes from Miletus appeared on the northern shores of the Black Sea near the present island of Berezan. This happened in the middle of the 7th century. BC According to archaeological research, it has been reliably established that there was no local settled population at that time here, as on almost the entire northern coast of the Black Sea. Excavations on the island have been carried out from 1884 to the present. They showed that the first settlement here was small, consisted of dugouts and half-dugouts, and was located only in the northern part of the island. It was called, according to the chronicle of the Greek writer Eusebius, Borysthenes or Borysphenida and was founded, according to his own data, around 645-644. BC Fragments of Greek pottery found at the settlement mainly confirm this date, although there are also isolated finds of earlier times. By the middle of the 6th BC, the Berezanians completely mastered the territory of the peninsula and, together with new groups of colonists from Miletus and other Greek city-states, began to settle in the surrounding area. A chain of small rural settlements stretched at that time from the modern city of Nikolaev in the north to Ochakov in the south. And the city of Borysphenites itself becomes noticeably more comfortable and comfortable. Now they are starting to build one-room adobe houses on stone foundations. From the second half of the 6th century. BC these houses become predominant in the development of the settlement. Multi-room houses are also appearing. Bronze arrow coins were in circulation in Berezan. They were cast in the form of two-bladed arrows, but without a sleeve, and at the same time imitated laurel, willow or olive leaves. The distribution area of these coins was limited to a small territory from Berezan to the later city of Olbia. Most of these coins were found on the territory of the settlement itself (Table 17.1). All this confirms that their coinage belongs specifically to the Berezan settlement. Some numismatists suggest that such a specific coin system of the Berezans is associated with the cult of Apollo the Physician. In any case, the coinage clearly indicates the leading role of the Berezan settlement in the archaic period in the political life of the entire Lower Bug region.

The most important find at Berezan is a letter on a lead plate from the second half of the 6th century. BC The discovery of such a letter is very rare, since lead, as a material for various works, was widely used by the Hellenes, and letters were usually not stored. The language of the letter indicates the Milesian origin of its author, and the fact that it was sent, judging by the text, to the neighboring city of Olbia, speaks of the close ties of the inhabitants of these two cities with each other. By the way, there are similar letters and inscriptions of a different kind in Olbia (Table 18.15).

At the end of the 7th - the very beginning of the 6th century. BC after the arrival of a new significant party of colonists from Miletus, the Berezans took part in the founding of a new policy, which was destined to become the main center of the area - Olbia. The settlement on Berezan after this began to gradually shrink in size and play the role of a commercial and industrial emporium of Olbia. Life on it died out in the 3rd century. AD

Olvia located almost in the center of the territory of the Dnieper-Bug estuary, already developed by the Hellenes, on two coastal terraces (Fig. 16). One of the terraces, the lower one, is rich in springs with excellent fresh water and is a convenient platform for creating a harbor. Here, in addition to the port facilities, there are numerous craft workshops and trade shops. Olviopolitov. This part of Olbia began to be called the “lower city”. Currently, most of this territory of the ancient city is flooded.

The second terrace - the upper one, protected from the west and north by wide and deep beams, was an excellent natural fortification. Here already in the 5th century. BC along the beams, fortress walls were built, inside of which there was

“upper city” with residential areas, temples, squares and other public buildings. The approval of a unified Olbian polis occurs by the middle of the 6th century. BC At this time, its civil community and the main state and religious institutions are finally taking shape.

Among the architectural structures in the city, there is an agora, around which there were shops and warehouses of merchants, and the offices of trapezites (money changers). On the square itself there were statues of gods and heroes, honorary decrees in honor of outstanding citizens of the city and proxies - decrees granting trade privileges and citizenship rights to foreigners. Various public buildings were also adjacent to the agora: at the entrance to the agora from the northern gate there was a courthouse - the dicastery; on the south side there is a gymnasium, a room for sports training of citizens; Prytanei - the seat of executive authorities and other structures.

In addition to the agora, the construction of religious buildings in special areas - temenos - was important for the city. A temenos of the second half of the 6th century was discovered in Olbia. BC The main temples of the city were built here, there was a sacred grove, and altars stood. The best preserved remains of the temple of Apollo Delphinius. It was built like an anta temple with a deep portico in front of the entrance. The walls of the temple were made of mud bricks on a stone foundation. Two wooden columns that formed the entrance were crowned with terracotta volutes made in the Ionian order.

Of the industrial buildings, the most interesting are ceramic kilns, which testify to the early widespread development of pottery production in the city.

In the VI - early first third of the V centuries. BC Around the city there was a whole series of rural settlements and seasonal camps numbering more than 70. The inhabitants of these settlements were engaged in farming, cattle breeding, fishing and hunting.

The heyday of Olbia began in the 5th - third quarter of the 3rd centuries. BC At this time, the city takes on a new look in accordance with the developed layout. Already in the first quarter of the 5th century. BC Fortress walls and towers were built. The height of the walls was 6-8 m, and the thickness was up to 3.5 m. These walls dominated the surrounding area. From them you could see everything that was happening around the city.

On the northern side of the agora in the 4th century. BC the front building is being erected - standing. It was intended for large gatherings, speeches by speakers, receptions, meetings and recreation for citizens. It was the largest building in the city. The building of the stoa separated the agora from the sacred area - the temenos.

During this period, the architectural design of the temenos was completed. It is separated from the adjacent streets to the west and east by stone walls and porticoes. A monumental stone altar is being erected in the center of the square, facing the Temple of Apollo Delphinius. The altar's limestone slabs were carefully crafted. Three stone slabs with cup-shaped recesses for making sacrifices were installed on the altar, and an extension was made in the center of its northern wall, which probably served as a pedestal for the statue of the deity.

In addition, on the sacred site during the IV-III centuries. BC a temple to Zeus, a series of altars, a number of utility rooms, a stone reservoir and drains for draining storm water are being built. A stone-paved path was laid along the facades of the temples, along the edges of which there were small altars, statues and inscriptions. Religious ceremonies were carried out here in honor of many Olympian deities, but Zeus and Athena were most revered. This is evidenced by numerous dedicatory inscriptions in honor of them, found in pit-favissas (bothros), which served to dump temple equipment that had become unusable.

Residential buildings of the townspeople are now all above ground, most of them made of mud brick on a stone foundation. One of the features of the Olbian urban construction of this time is the presence in the houses of basements with stone walls, well equipped for living in winter. Rich stone houses with courtyards also appeared.

During the IV-III centuries. BC The first well-fortified estates appeared in the immediate area of the city. But the leading type of settlements in the choir continued to be unfortified settlements. The rural population of Chora reaches 28 - 31 thousand people, while the population of Olbia itself ranges from 14 to 21 thousand people. The spiritual culture of the inhabitants of Chora was purely Greek, with some distinctive features characteristic of Olbia itself. The villagers spoke Greek, used Greek writing, and were quite literate. Although, of course, among them there was a certain (small) percentage of people from the barbarian population, mainly Scythian and Thracian.

From the second half of the 3rd century. BC Olbia is entering a period of protracted crisis. Its main reasons were environmental changes and the increased migration of nomadic tribes in connection with this, which led to an increase in the number of military clashes, conflicts of the city with its barbarian and Greek neighbors and further social stratification of citizens. The plight of the city is most vividly described by the decrees adopted at that time in honor of their own and foreign citizens who helped the city in difficult times. The most famous and informative among them is the decree in honor of the Olbian citizen Protogen.

Olbia's dependence on Scythia is also increasing. The city mints coins in the name of the Scythian king Skilur. In one of the poetic tombstone inscriptions of that time, Olbia is directly called a Scythian city. Some Olviopolitans now enter the service of the Scythian king and become his active assistants. From honorary inscriptions we know the name of such an Olviopolitan, Posideius, who became the commander of the Scythian fleet and defeated the pirate tribe of the Satarchs.

By the end of the 2nd century. BC The military-political and economic crisis is deepening even more. Agora and temenos cease to exist. On the temenos, the temples and the main altar are dismantled. All water supply systems of the agora also cease to operate. Vacant lots are appearing in place of a number of residential areas. The state's large rural districts have been in decline for a long time. The Olbian decree in honor of a certain Nikeratus testifies to the constant military clashes of the Olbians with neighboring barbarian tribes.

Roughly around 106 BC. The Scythian protectorate over Olbia is replaced by the protectorate of the Pontic kingdom of Mithridates Eupator. According to the terms of the treaty, a Pontic garrison is introduced into the city, which protects it from enemy raids. For some time the situation in the city improved. The minting of its own copper coins began again. But soon after the defeat of Mithridates by the Romans, the military pressure of the barbarians intensified again. By the middle of the 1st century. BC On the territory of present-day Romania, a powerful association of Getian tribes is created. Its ruler Burebista begins a series of conquests in the surrounding territories. In the fifties, it falls on Olbia, captures and completely destroys the city.

Several decades after the Getaean defeat in the middle of the 1st century. BC Olvia was empty and lay in ruins. Life is reborn here only at the beginning of the 1st century. AD At this time, a new transgression (rise) of sea level begins, during which Berezan is separated from the mainland and becomes an island. The complex of material culture of Olbia remains generally ancient, but the architectural appearance of the city is increasingly rusticated. During the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero (54-68), Olbia fell into the orbit of Roman politics. During the reign of Emperor Trajan, the regular flow of Roman denarii into Olbia began, Roman names appeared among the inhabitants of the city, and judging by one of the Olbian inscriptions, a small Roman military garrison appeared in Olbia. From the second quarter of the 3rd century. AD The gradual decline of Olbia begins. Around 235, the minting of its own coins finally ceased. The inhabited area of the residential part of the city itself now occupies no more than a third of its former territory. During the 3rd century. AD the city was twice destroyed by the Goths. By the time of the Hun invasion, it was completely abandoned by its inhabitants. Even earlier, the settlements of the city's chora were abandoned.

The only colony of the Greeks of the Dorian tribe in the Northern Black Sea region became Chersonese Tauride- a city now located within the city of Sevastopol, on a cape at the mouth of Karantinnaya Bay (Fig. 17). According to written sources, the founders of Chersonesos were residents of the southern Pontic city of Heraclea and a small group of residents of the island of Delos. This information dates back to around 422/21. BC But this date for the founding of the city is contradicted by archaeological research materials - painted Ionian, black-figure and red-figure ceramics of the second quarter of the 6th century. BC and a small cultural layer of the 6th-5th centuries. BC at the settlement. All this gives reason to believe that the early city was founded in the last quarter of the 6th century. BC

The early city was located on the western shore of Quarantine Bay, on a natural hill, which was bounded on the west and east by bays convenient for anchoring ships, on the north by the sea, and on the south by fairly deep ravines. These natural fortifications from the second half of the 4th century. BC were reinforced with powerful stone defensive walls with numerous towers. Parts of these walls, towers, city gates, sally gates and other structures have still been preserved. The area of the first settlement on the site of Chersonesos is small - about 10-11 hectares. Its population at that time was no more than 1000 people.

The initial allotments of the citizens were small and located directly at the borders of the city fortifications on the Heraclean Peninsula. Traces of the earliest demarcation of land plots can be traced on the Mayachny Peninsula, located at a distance of about 9 km from Chersonesos. Its territory was separated by a narrow (about 200 m) isthmus from the rest of the Heraclean Peninsula and protected by two rows of walls with towers. The walls and towers were designed to protect the allotments of the Chersonesos from the raids of their Taurian neighbors, with whom the Chersonesites always had hostile relations.

The comparatively small territory of the Mayachny Peninsula (about 380 hectares) allows us to conclude that the initial allotments of the city residents were small. The rocky soil of this area allowed the production of mainly grapes. And therefore the city did not have enough of its own bread. They begin to import it from Olbia, which from the end of the 5th century. BC becomes the main trading counterparty of Chersonesos.

From the second quarter of the 4th century. BC The rapid growth of the economic and political power of the polis begins. The first settlement arose outside the city limits in the lower reaches of the Karantinnaya Balka, and then additional strengthening of the territory of the Mayachny Peninsula, 10 km west of the city, was carried out. From that time on, the actual and systematic development of the agricultural territory of the Heraclean Peninsula began by the Chersonesites.

The entire land here, amounting to about 10,000 hectares, was divided into a system of almost rectangular land plots (klers), separated from each other by mutually intersecting roads with a width of 4.5 to 6.5 m. Such boundary roads, on both sides of which were laid stone fences at least two meters high and about one and a half meters thick, were narrow corridors stretching for many kilometers. Moreover, each plot of land was also divided into separate plots by walls up to 2 m high.

In total, in the vicinity of Chersonesus on the Heraclean Peninsula there are about 430 plots. Large (on average up to 26.5 hectares) estates appear on them, surrounded by stone fences with an obligatory stone tower in the corner (Fig. 18). The farther the estates were from Chersonesus, the more fortified they were. The estate and allotment constituted the main economic unit - the household of a Chersonesos citizen. The number of plots approximately corresponds to the number of families of Chersonesos. It is estimated that to process such a plot the owner needed 25-30 workers.

Two-thirds of the area of the clairs was usually occupied by vineyards and orchards. Experts believe that with the most normal harvest, about 95,000 liters of wine could be produced on such a plot. Taking into account the consumption of family members and estate workers of no more than one third of this amount, another 50-70 thousand liters of wine were sold. To sell such a quantity of wine, naturally, its owners needed a large amount of tons  ares. This caused an increase in ceramic production in the city. The volume of Chersonesos amphorae was 17-19 liters. This means that about 3,000 amphorae were required to spill the harvest from the estate alone. And this is the usual cargo of an average Greek merchant ship. Naturally, in exchange for such a quantity of its marketable products, the Chersonesos could well have acquired all the other products it needed and

ares. This caused an increase in ceramic production in the city. The volume of Chersonesos amphorae was 17-19 liters. This means that about 3,000 amphorae were required to spill the harvest from the estate alone. And this is the usual cargo of an average Greek merchant ship. Naturally, in exchange for such a quantity of its marketable products, the Chersonesos could well have acquired all the other products it needed and

Rice. 18 handicraft products. Thanks to the organization of its own choir, Chersonesos from the end of the 4th century. BC became one of the main suppliers of wine in the Black Sea region and successfully competed in this regard with the policies of Greece itself and Asia Minor.

The land plots of the Chora of Chersonesus are monuments of ancient agriculture that are unique in their preservation. They allow the most complete and objective assessment of the nature of the city’s agriculture. In addition, in the immediate vicinity of Chersonesus, the remains of three small suburban specialized villages of winemakers, potters and masons have been identified.

By the middle of the 4th century. BC The Chersonesos subjugated the city of Kerkenitis and founded a whole series of new rural estates and fortresses on the coastal lands of northwestern Crimea. The largest of them were the fortresses “Chaika”, Kara-Tobe, Belyaus, Western Donuzlav settlement, Kulchuk, Bolshoi Kastel, Panskoe 1, the city of Kalos Limen (Beautiful Harbor) and the northernmost settlement of Maslina. All of them were located on the shores of bays and bays. Most of the citizens' plots located here were agricultural complexes focused on bread production. In total, the Greeks developed about 32,000 hectares of the most fertile lands in this region.

By the end of the 4th century. BC The area of the city more than doubles, reaching 24-26 hectares, and the population increases to 6-10 thousand people. The city is surrounded by new powerful fortress walls, made of large, well-hewn blocks tightly fitted to each other. In open areas they rise 3-4 m, and in ancient times the height of the wall reached eight meters. The height of the towers was even greater. The city had several gates. The best preserved gate is the one leading to the port part of the city.

The streets of Chersonesos began right from the gate. The city was stretched from southwest to northeast. Longitudinal streets, 6.5-6.7 m wide, ran in the same direction. They were intersected by narrower (up to 4.5 m) transverse streets. The streets were paved with stone and drainage channels ran under the pavement. Its length is almost 900 m. In total, 8 longitudinal and 20 transverse streets are open in Chersonesos.

The center of the city was occupied by the acropolis and agora. The most important public buildings were located here. In its southern part, not far from the city gates, there was a theater. It was built in the middle of the 3rd century. BC and then was rebuilt several times. During the Roman period, the theater accommodated about 3,000 spectators. It functioned until the middle of the 4th century. AD Another important building in the city center was the mint, of which only the basement with massive walls has survived. 43 bronze mugs for minting coins were found here. Somewhere here were the bouleuterium - the city council building and the dicastery - the courthouse.

As in other Greek city policies, the city center was decorated with monumental sculpture - statues of deities and heroes of the city. Several marble pedestals of such statues with inscriptions have been found. There were also slabs with decrees and regulations of the city. One of the most important finds of this kind is the text of the Chersonese oath, which young people took when joining the ephebes.

The residential areas of the city looked much more modest in comparison with the public center. Along narrow straight streets with gutters running along them, there were blocks of solid identical stone fences and the same blank walls of houses. Only occasionally these walls were interrupted by small windows and narrow gates leading to the courtyard of the house. 3-4 houses made up a standard block. The residential buildings of the Chersonesos are mostly uniform. Usually their courtyard is in the center. Living quarters and storage rooms surround it on all sides. In the courtyard there was usually a well or a cistern carved into the rock to collect rainwater. The floors in the houses are earthen with clay plastering, the walls are plastered and decorated with encaustic paintings in red and yellow. The roofs of the houses are tiled, and quite a lot of tiles are imported from Sinope. The area of such houses usually did not exceed 210 sq.m. Some of them contain altars made of slabs or made of separate blocks.

Along with row houses there were also larger manor houses. In one of these houses in the northern part of the city, a home sauna with a mosaic floor has been opened. The mosaic is made of yellow and bluish sea pebbles, with rare inclusions of red pebbles, and depicts the image of two naked female figures (Table 18, 16).

In addition, several groups of fish-salting tanks, a huge amount of remains of various fishing gear, and traces of salt production have been discovered in the city. The export of salted and dried fish was undoubtedly one of the important sources of income for the townspeople. All basic crafts were developed in Chersonesos.

In the first decades of the 3rd century. BC A series of Scythian-Chersonese wars begins. The Scythians destroyed a number of Chersonese settlements on the shores of what are now Yarylgach and Vetrennaya bays. Those residents who did not manage to leave died in their homes and fortifications. By the turn of the 3rd-2nd centuries. BC Almost the entire agricultural territory of Northwestern Crimea falls into the hands of the Scythians. Then the nearest districts of Chersonesos were subjected to their raids. Not having sufficient forces of their own to restrain the enemy’s onslaught, the Chersonesos turn to the Sarmatians, the enemies of the Scythians, for help. At the same time, they are looking for new allies and turn to the king of the state of Pontus Pharnaces. In 179 BC. the contract was concluded. Its text is preserved among the inscriptions of Chersonesos. And when the Scythians besieged Chersonesos itself, the Pontic people came to the aid of the city. The Chersonese decree in honor of the Pontic commander Diophantus tells about the events of those years.

For some time the city was under the rule of the Pontic king Mithridates Eupator, and after his death it became dependent on Rome. The Romans to protect the Black Sea coast from barbarians in the middle of the 1st century. AD, they introduced a garrison into Chersonesos, and to control the mountainous regions of Taurica on Cape Ai-Todor, seven kilometers west of modern Yalta, they built the Kharaks fortress. The Roman garrison was located in the southeastern part of Chersonesos, which was a citadel with an area of about 1 hectare. This area was well fortified on the ground side and separated from the rest of the city by a separate wall. In the citadel, a barracks, baths, an altar in honor of Jupiter, tiles with legion marks, tombstones and other traces of the presence of Roman legionaries in the city were discovered. Judging by the size of the citadel, the Roman garrison was small - no more than 500 people. But in addition, some of the soldiers were stationed in special guard posts in the vicinity of Chersonesus. In addition to ground forces, Chersonese was also guarded by Roman warships. The ships of the Romans patrolled the coast of Taurica, almost completely eradicating opportunities for piracy for the local coastal tribes. The barbarian raids of the era of the Great Migration of Peoples did not affect Chersonesos. Under Emperor Justinian I, the city and the entire southern part of Taurica were included in the Byzantine Empire, within which the city survived until 1399.

In the last quarter or even at the end of the 7th century. BC Greek settlements also appeared in the North-Eastern Black Sea region. The polis began to play a leading role among them Panticapaeum, which gradually united the rest within a single state - Bosporan Kingdom. The harbor of Panticapaeum was located on the site of the center of the modern city of Kerch (Fig. 19). There was obviously an agora near the harbor. Most of the residential areas and craft workshops of Panticapaeum are located on the slopes of a high rocky mountain, rising 91 m above sea level and called Mount Mithridates. At the top of this mountain was an acropolis, the remains of which have recently been excavated and reconstructed. Temples and public buildings were located inside the acropolis. The main patron deity of Panticapaeum was Apollo, and it was to him that the main temple of the acropolis was dedicated. Over time, the entire city was surrounded by a powerful stone wall.

In the vicinity of the city there was its necropolis, which was very noticeably different from the necropolises of other Hellenic cities. In addition to the usual ground burials for Hellenes at that time, the necropolis of Panticapaeum also consisted of long chains of mounds stretching along the roads from the city to the steppe. On the southern side, the city is bordered by the most significant ridge of mounds, today called Yuz-Oba - a hundred hills. Representatives of the nobility of the state, Scythian and Maeotian leaders who lived in the city are buried under their mounds. The mounds constitute one of the most striking attractions in the vicinity of Kerch.

In addition to Panticapaeum, the most significant cities of the Bosporus were: on the Kerch Peninsula - Theodosius and Nymphaeum, on the Taman Peninsula - Phanagoria, Hermonassa, Gorgippia and Kepi. Also widely known thanks to archaeological research are such relatively small cities as Myrmekiy, in which the most significant wine-making complexes of the Bosporus were discovered, and Tiritaka, which became famous for its grandiose fish-salting facilities. An expedition from the University of Nizhny Novgorod explored the city of Kitey, best known for its unique temple complex for the ancient world with a huge ash hill.

All these cities were the economic centers of their regions and the building remains and materials found in them are similar to those from Olbia, Chersonesus and Panticapaeum, differing only in quantitative ratio. Having survived all the blows of the barbarians, the Bosporan state existed as an independent whole until the end of the history of the ancient world.

Literature

1. Ancient states of the Northern Black Sea region // Archeology of the USSR. -M.: Nauka, 1984. - 392 p.

2. Ancient monuments of Crimea. - Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, 2004. - 235 p.

3. Blavatsky V.D. Panticapaeum. - M.: Nauka, 1964. - 188 p.

4. Blavatsky V.D. Ancient archeology and history. - M.: Nauka, 1985. - 231 p.

5. Gaidukevich I.B. Bosporan cities. - L.: Nauka, 1981. - 365 p.

6. Butyagin A.M., Vinogradov Yu.A. Mirmekiy. - St. Petersburg, Nauka, 2006. - 215 p.

7. Gaidukevich V.F. Bosporan kingdom. - M.-L.: USSR Academy of Sciences, 1949. - 374 p.

8. Zubar V.M. Chersonese Tauride. - Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, 1997. - 267 p.

9. Zubar V.M., Ruslyaeva A.S. On the shores of the Cimmerian Bosporus. – Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, 2004. - 315 p.

10. Krapivina V.V. Olvia. Material culture I-IV centuries. AD – Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, 1993. - 276 p.

11. Kruglikova I.T. Ancient archaeology. - M.: Higher School, 1984. - 216 p.

12. Molev E.A. Hellenes and barbarians in the Northern Black Sea region. - M.: Tsentrpoligraf, 2005. - 384 p.

13. Rusyaeva A.S., Rusyaeva M.V. Olvia of Pontus. – Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, 2004. - 234 p.

14. Khrapunov I.N. Ancient history of Crimea. – Simferopol: Share, 2007. - 272 p.

The name of the northern coast of the Black and Azov Seas in historical literature. A significant part belonged to Kievan Rus; from the end 18th century in Novorossiya... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

Northern Black Sea region in the I-II centuries. n. e.- Socio-economic and political system During the period under review, a further evolution of the slave-owning mode of production was observed on the territory of the Northern Black Sea region. Here this process is complicated by the fact that the Northern Black Sea region... ... World History. Encyclopedia

Northern Black Sea region- the name of the northern coast of the Black and Azov Seas in historical literature. A significant part of the Northern Black Sea region was part of the Old Russian state; from the end of the 18th century in Novorossiya. * * * NORTHERN BLACK SEA REGION NORTH... ... Encyclopedic Dictionary

I.6.10. Northern Black Sea region- ⇑ I.6. Asia Minor and the Black Sea region ca. 3000 2000 BC Yamnaya culture (Neolithic Chalcolithic). OK. 2000 1300 BC catacomb culture (bronze). OK. 1300 800 BC timber culture (iron). I.6.10.1. Cimmerians...Rulers of the World

Black Sea region- ... Wikipedia

Northern Azov region- Azov region is a geographical region around the Sea of Azov, divided between Russia and Ukraine. The linking of the term only to Ukraine is hypertrophied. Then the clearly truncated area is indicated in the South-East of Ukraine (the territory of the south of Donetsk and... ... Wikipedia

Northern Black Sea region- the name of the northern coast of the Black Sea and adjacent areas, mainly in relation to the time of Greek and Roman colonization (VI century BC, II century AD) and the era of the Great Migration of Peoples (IV VII centuries). Along with... ... Art encyclopedia

Western Black Sea region- Romania, Bulgaria, Türkiye; 1878 ... Wikipedia

Southern Black Sea region- This article or section needs to be revised. Please improve the article in accordance with the rules for writing articles... Wikipedia

Genoese colonies in the Northern Black Sea region- Genoese fortress in Sudak (reconstruction). Genoese colonies in the Northern Black Sea region, fortified trading centers of Genoese merchants in the 13th-15th centuries ... Wikipedia

Books

- Civilizations. Theory, history, dialogue, future. Volume 3. Northern Black Sea region - space of interaction of civilizations, B. N. Kuzyk, Yu. V. Yakovets. Along with local civilizations, there are also spaces for their interaction. The most striking example of such a space is the Northern Black Sea region - a field of interaction between civilizations and... Buy for 3547 rubles

- Northern Black Sea region in the era of antiquity and the Middle Ages. The collection of scientific articles is devoted to the history and culture of the Northern Black Sea region in the era of antiquity and the Middle Ages. It includes articles by a number of leading antiquarians in Russia, Ukraine and Germany. For the first time...

Introduction

1. Ancient states of the Northern Black Sea region

2. State-political structure

3.1 Olbia

3. 2 Taurian Chersonesos

3.3 Bosporan State

Conclusion

List of used literature

Introduction

The first cases of visits to the Northern Black Sea region by Greek sailors occurred at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. In the first half - middle of the VI century. to AD the Greeks founded Olbia, at the end of VI - Tire, Nikonium (on the Dniester estuary), Kerkinitis. At the same time, a small Ionian settlement appeared in the South-Western Crimea. Perhaps it existed by the last quarter of the 5th century. BC, when immigrants from Heraclea Pontius founded Chersonesos in its place. In the second half of the VI century. BC most of the cities of Bosporus emerge: Panticapaeum, Theodosius, Nymphaeum, Miyrmekiy, Tiritaka, Phanagoria, Hermonassa, Kepi. It was at this time that almost complete development of the rural areas around these cities took place, where many settlements appeared. In addition to Chersonesus, most of the cities mentioned were founded by people from the region of the Asia Minor city of Miletus.

The colonization of the Northern Black Sea region was part of the so-called Great Greek colonization of the VIII-VI centuries. BC It was predetermined by a number of reasons, the most important of which was relative overpopulation, when all the lands in mainland Greece were already distributed. The “superfluous” people were forced to look for a better fate in other places that were not so densely populated. The Greeks, the founders of the Northern Black Sea cities, were mostly farmers, partly traders, artisans, etc. At the early stage of their existence in their new homeland, they were engaged in agriculture - they sowed wheat, barley, millet, planted gardens, gardened, raised livestock, etc. p. Their other activities - crafts, trade - were secondary. So, the Greek colonization of the Northern Black Sea region was at first of an agrarian nature (although, of course, some colonists abandoned Greece for other reasons, for example, having experienced defeats in military and socio-political conflicts). It should be emphasized: the term “colonization” in this case should be understood only as the economic development of the Northern Black Sea region by the Greeks, and peacefully, since no one lived where they settled - on the sea and estuary coasts. The newly founded colonies did not depend on the metropolitan cities, although they maintained good relations with them, even established agreements regarding mutual assistance in trade, granting equal rights to citizens of both policies, and had common cults and chronologies with them.

Colonies were mainly founded, obviously in an orderly manner, when the head of a group of colonists, an oikist, was elected or appointed in the metropolis. At the site where the new city was founded, areas for buildings and agricultural areas were demarcated, and places were allocated for religious and public needs. However, sometimes colonization could also be spontaneous.

The settlers developed, in essence, only a narrow (approximately 5-10 km) strip of sea and estuary coastline. Therefore, they could not in any way harm the nomads of the Black Sea steppes. The exceptions in this regard are Chersonese, near which the Tauri lived, and some cities of the Asian Bosporus, next to which the tribes of the Sinds and Maeots lived. But we do not have any evidence of clashes between colonists and aborigines.

1. Ancient states of the Northern Black Sea region

The development of the Northern Black Sea coast by Greek settlers occurred gradually, generally in a direction from the west to the east. VI Art. BC in general, there were times when most of the northern Black Sea states were established. Each of them had its own history, but since they all interacted closely with the ancient world, as well as with the barbarian environment, many similarities can be traced in their development. The almost thousand-year history of these states is divided into two large periods and several stages.

The first period lasted from the second half of the 7th century and approximately to the middle of the 1st century. to AD It was characterized by close cultural and economic ties both with mainland Greece and with surrounding tribes, which were predetermined by the relative stability of general historical development. The material and spiritual life of the colonists was absolutely dominated by Hellenic traditions, thanks to which this period can be conditionally called Greek, or Hellenic. It should, however, be kept in mind that the Bosporan state is currently being created, which included not only the Hellenic city-states located around the Kerch Bay, but also the tribes of the Sinds and Maeots mentioned above. This gives grounds to consider the Bosporus a Greek-barbarian state, whose rulers were probably of local origin. Characteristically, barbarization had almost no effect on the culture and life of the population of the Bosporan cities and their rural areas. In general, the number of barbarians among the inhabitants of the North Black Sea ancient colonies was insignificant.

At the archaic stage of the first period (second half of the 7th - beginning of the 5th century BC) in the south of present-day Ukraine, the formation of states took place, and their active contacts began with the Greek cities of the Eastern Mediterranean, in particular Ionia. Typical is the dugout residential development of most North Black Sea towns, although already in the VI century. BC e. in the largest of them, temples were built (Olbia, Panticapaeum), and agora complexes were formed (the area around which administrative and public buildings, shops, places of worship, altars, etc. were located). Crafts and trades were born, trade developed, and coinage emerged. Generally peaceful contacts between the Greek settlers and the surrounding nomadic tribes begin. Ancient cities in the VI century. to AD did not yet have fortifications (their remains, dated to the end of the 6th - beginning of the 5th century BC, were identified only in Tiritaka).

At the second - classical - stage of the first period (beginning of the 5th - second third of the 4th century AD), the gradual flourishing of states begins; cities grow and take on the appearance typical of ancient policies with developed land-based, including residential, development. They contain monumental structures, defensive fortifications and towers. The minting of its own coins is introduced. Trade and cultural ties with the ancient world are strengthening. So, perhaps, approximately in the middle of the 5th century. BC Olbia was visited by the “father of history” - Herodotus (the basis for this assumption is provided by an analysis of his story about the Scythian king Skiles, who had his own palace in Olbia). The ancient cities of the Northern Black Sea coast are well known in the metropolises; they are mentioned in various sources.

At the end of the second third of the IV century. In the development of the ancient Northern Black Sea states, there is a short-term crisis caused mainly by foreign policy factors (in particular, the collapse of Greater Scythia and the expansion of the troops of Alexander the Great: ancient sources mention in 331 AD the siege of Olbia by the troops of the commander Alexander - Zopyrion). From that time on, the last stage of the Hellenic period in the life of the cities of the Northern Black Sea region began - the Hellenistic (last third of the 4th - middle of the 1st century AD), which was first marked by maximum economic development, the rise of agriculture, crafts, trade, culture in general. Nevertheless, already from the second half of the III century. to AD (in the Bosporus - later) a crisis is gradually brewing. The aggression of the Scythians in Western Crimea, the movement of barbarian tribes in the Lower Bug and Dnieper regions lead to the decline of ancient cities - their main economic base. Olbia was forced to pay tribute to various local kings, in particular Saita-farn, and in the II century. to AD even falls into semi-dependence on the Crimean Scythia Minor.

The second large period in the history of the ancient states of the Northern Black Sea region - the so-called Roman (mid-1st century AD - 70s of the 4th century AD) - is characterized primarily by the inclusion of Tiri, Olbia, Chersonesos into the Roman province - Lower Moesia. This period was marked by the instability of the military-political situation, determined by the barbarization of the population, the naturalization of the economy, and the partial reorientation of cultural and economic ties. The states of the Northern Black Sea region became for the Roman Empire a kind of barrier against the pressure of nomadic tribes on its eastern borders, which ran along the Danube. There is some economic growth in Tiri, Chersonese, and Bosporus, and their culture is gradually becoming Romanized.

In the second period of the existence of the ancient Northern Black Sea cities and their surroundings, three main stages can be distinguished. The first begins in the middle of the 1st century. BC, when the policies of these cities gradually reoriented towards Rome. First, Roman troops appear on the northern coast of Pontus, but at the same time their interference in local affairs, in particular in the Bosporus and Chersonese, is quite noticeable. They help the ancient population in their struggle against the surrounding tribes. The famous campaign carried out to help Chersonese in its skirmishes with the Scythians by Plautius Silvanus (63 AD), the ruler of Lower Moesia, also belongs to these times. At the same time, the Northern Black Sea states in Art. II. AD They conflicted not only with barbarians, but also with the Romans and even among themselves (Bosporus and Chersonese). Despite such seemingly unfavorable circumstances, the economies of these states gradually emerged from the crisis. The rural districts of Olbia are being revived, and a significant number of new settlements are appearing in the Bosporus. The rural districts of Chersonesos and Tiri are functioning (some of the settlements in these districts obviously belonged to barbarians, but they also worked for the economy of ancient cities). Along with agriculture, handicrafts and trades (salt making, fish salting, winemaking) are gaining significant development - especially in Chersonesos and Bosporus. Trade relations with the North Black Sea, Asia Minor, Italian, and Western Black Sea cities are intensifying.

The second stage covers the time from the middle of the II to the middle of the III century. AD, when permanent detachments of Roman troops were stationed in Tire, Olbia, Chersonese, Charax, and these cities themselves were subordinate to Lower Moesia. The Bosporus is also in a certain political dependence on Rome. In conditions of relative military-political stability, the economies of the North Black Sea states are achieving the highest development.

The third - last - stage begins from the second half of the III century. AD, when, in order to protect the borders of the Roman Empire from the Goths, garrisons of Roman troops were withdrawn from the Northern Black Sea region to the Danube. Invasions of nomads, in particular the Goths, virtually destroyed rural areas. Almost all ancient states finally ceased to exist in the 70s. In the 1940s, only Chersonesus and Panticapaeum survived under the attacks of the Huns, which eventually became part of the Byzantine Empire.

2. State-political structure

The North Black Sea policies were slaveholding democratic or aristocratic republics, where slaves, women and foreigners did not have citizenship rights (although, for great services to the policy, foreigners could be granted such rights). The highest bodies of legislative power were the people's assembly ("people") and the council.

The People's Assembly, in which all full-fledged citizens took part, resolved issues of foreign policy, defense, monetary circulation, providing the population with food, granting privileges to merchants, civil rights to certain individuals, etc. The council prepared certain issues for consideration at the meeting, controlled the actions of the executive branch, and checked the business qualities of candidates for public office. The executive power consisted of different boards - magistrates or individual officials - magistrates. Typically, the greatest rights were enjoyed by the colleges of archons, which convened the people's assembly, led other colleges, and monitored the state of finances.

There were special colleges that dealt exclusively with financial or military affairs (college of strategists), trade (college of agoranomists), improvement of the city (college of astynomians), etc.

Individual magistrates supervised specific city pledges (gymnasiarchs, heralds, secretaries, priests, etc.). There were also judicial institutions, which consisted of several departments. Judges and witnesses took part in legal proceedings, and at times changes occurred in state and political life. Thus, the policies of the Cimmerian Bosporus in 480 BC. united under the rule of the Archeanactids into a single Bosporan kingdom, although even after that they remained practically independent in their internal affairs. And when in the first centuries of the new era Chersonese, Olbia and Tyre became part of Lower Moesia (see above), they also retained local self-government.

3. Cities of the Northern Black Sea Coast

3.1 Olbia

The area of the settlement that has survived is approximately 10 hectares. The remains of dugouts were discovered, which in the last quarter of the 6th century. BC modified by ordinary Greek land houses. The city in some of its districts had a rectangular layout. Olbia (in ancient Greek means “happy”) is a cell of the Olbian state. Located on the right bank of the Yuzhnobugsky estuary near the modern village. Parutina, Ochakovsky district, Nikolaev region. Founded around the middle of the 6th century. BC came from the Miletus area and existed by the middle of the 3rd century. AD After this life in Olbia, it barely smoldered by the beginning of the 4th century. AD, but by that time it had already completely lost the features inherent in the ancient center.

Topographical Olbia consisted of three parts - Upper, Terasnaya and Lower. The latter, after the death of the city, was largely destroyed by the waters of the estuary. At the flowering stage - at the end of the IV - in the III century. BC - Olbia occupied an area of about 55 hectares, its population was close to 20 thousand.

In the history of the city and the state as a whole, two large periods can be traced. The first century covers the time from the establishment of a colony here to the middle of the 1st century. BC Built in the second half of the VI century. BC single-chambered spadefoot and half-dugout, in the V century. BC Olbia takes on the appearance usual for an ancient Greek city. In the 5th century BC in it, behind Herodotus, there already existed fortifications, as well as the palace of the Scythian king Skil. Residential buildings in Olbia are usually one-story with basements, less often two-story. The remains of the agora have been discovered - the square around which shopping arcades, courthouses, various magistracy, and gymnasiums were concentrated. Sacred areas have also been identified - temenos (one of them dedicated to Apollo the Dolphin, the second to Apollo the Physician), altars, remains of temples, auxiliary buildings, remains of defensive structures, in particular the Western Gate, flanked by two large towers.

Olvia was well known in the ancient world. In the 5th century BC Let us remember that Herodotus visited her. For some time it was part of the Athens Maritime Union, its trade and cultural ties reached not only the Black Sea cities, but also the Eastern Mediterranean - Greece, Asia Minor, Alexandria of Egypt. The Olbian state had its own money - at first it was cast “dolphins”, a little later - asses (large coins with the image of the face of Medusa the Gorgon, the goddesses Athena or Demeter on the obverse, and symbols of the polis on the reverse), and from the middle of the 5th century. BC begins to mint coins common to the ancient world. The economic base of the policy was agriculture - currently the rural districts of Olbia occupied the coast of the Dniester, Yuzhnobugsky, Berezansky and Sositsky estuaries, as well as the Kinburn Peninsula. The total number of rural settlements at different stages of the state's existence was close to two hundred. Crafts and trade developed. Fisheries played a relatively small role.

In the period from the last third of the IV to the middle of the III century. to AD The Olbian state achieved the highest economic growth. At present, in particular, a new type of rural settlements has emerged in the form of so-called collective estates. Nevertheless, already from the end of the III century. BC begins a gradual decline.

In II Art. BC Olbia finds itself under the protectorate of the king of Scythia Minor (in Crimea) Skilur. From the end of Art. II. BC to the 70s of the 1st century. BC it was in the power of Mithridates VI Eupator (121-63 BC) - the king of the Pontic state.

However, already at the end of the first century. BC begins the gradual revival of Olbia and the settlements of its rural surroundings, which marks the beginning of the second period, which generally passed under the sign of Roman influences. At this time, the territory of the settlement was reduced by almost three times, its buildings were crowded and generally poor. Around the middle of the 1st century. AD Olbia becomes dependent on the Scythian or Sarmatian kings, but is soon freed. In the middle of the II century. AD, for the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161), the Roman provincial troops built a citadel here and placed their pledge in it, and for the emperor Septimius Severus (193-211), the city became part of Lower Moesia. II - first half of the III century. AD became the period of the highest prosperity of Olbia during Roman times. From these times, the remains of defensive structures, residential buildings, pottery kilns, and citadel structures have been preserved. Among the townspeople, the percentage of people from barbarian backgrounds is increasing. Nevertheless, even as part of Lower Moesia, Olbia retains its autonomy, mints its own coins, and trades with the ancient world and surrounding tribes. Rural settlements in the first centuries of our era already had fortifications from ditches and ramparts or walls under construction. In the 40s and 70s, then those years of the III century. AD Olvia is ready to test the bulk; The Roman pledge leaves her to the mercy of fate. Among the ruins of the city for some time - by the first half of the 4th century. AD - there are a few inhabitants, which probably include people from the Chernyakhov tribes. Life in Olbia finally comes to a standstill no later than the second quarter of the 4th century. AD

3.2 Taurian Chersonesos

The name comes from the Greek word for "peninsula". The ruins of this ancient city are located on the outskirts of Sevastopol. Chersonesos was founded in 422/421 BC. immigrants from Heraclea Pontius. Even earlier - at the end of the VI century. BC - there was a small Ionian settlement here. Chersonesos is one of the three large ancient cities of the North Black Sea that survived until the late Middle Ages. The heyday of the state occurred at the end of the IV-III century. to AD The territory of Chersonesos itself reached 33 hectares (part of the city is now destroyed by the sea), and the population was no less than 15 thousand inhabitants.