Before us is perhaps the most famous painting by Ilya Repin - “Barge Haulers on the Volga”. The painting of this canvas was preceded by the artist’s journey along the Neva and Volga, the writing of several sketches dedicated to the life of the barge haulers. Repin began to get acquainted with the life and everyday life of barge haulers in 1870, and three years later the painting “Barge Haulers on the Volga” appeared in its final version.

The general impression of the picture is the following - several exhausted people are pulling a barge against the current in a hot summer sun. Tattered clothes show that this work is extremely low-paid, and only extreme poverty can push a person to such work. Some of the barge haulers are dressed in such shabby clothes that their bodies can be seen through the holes.

Repin gave each of the characters its own character. Someone is calm, just steps forward and pulls his weight. He understands that any work, even the hardest one, will end someday, but he will have time to earn money so that his family does not need it in the winter.

The barge haulers walk towards the viewer, but do not cover each other's faces. One of the barge haulers can be seen loosening his strap and lighting a cigarette, but the other members of the artel take this calmly, understanding that he needs a break.

The young barge hauler in the center is exhausted and cannot pull the strap as expected. Only one elderly barge hauler, who is depicted in the center, does his job clearly. He is wearing clothes that are completely unsuitable for the summer heat - but he understands that light clothing will quickly become unusable.

The picture displeased many critics, but, nevertheless, became one of the most famous works Ilya Repin.

Year of painting: 1873.

Dimensions of the painting: 131 x 281 cm.

Material: canvas.

Writing technique: oil.

Genre: genre painting.

Style: realism.

Gallery: State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

The painting “Barge Haulers on the Volga,” which made Ilya Repin famous, has caused mixed reviews since its appearance. Some admired the artist’s skill, others accused him of deviating from the truth of life. Why did the famous painting provoke a scandal? state level, and how much did Repin actually sin against reality?

These images of unfortunate ragamuffins earning a living through backbreaking labor are familiar to everyone. school textbooks. Barge haulers in the 16th-19th centuries. were hired workers who used tow lines to pull river boats against the current. Barge haulers united in artels of 10-45 people, and there were also women's artels. Despite the hard work, barge haulers could earn enough during the season (spring or autumn) to then live comfortably for six months. Due to need and poor harvests, peasants sometimes became barge haulers, but mostly tramps and homeless people did this work.

I. Shubin claims that in the 19th century. The work of barge haulers looked like this: a large drum with a rope wound around it was installed on the barges. People got into the boat, took with them the end of the cable with three anchors and sailed upstream. There they threw anchors into the water one by one. The barge haulers pulled the cable from bow to stern, winding it around a drum. In this way, they “pulled” the barge upstream: they walked backward, and the deck under their feet moved forward. Having wound the cable, they again went to the bow of the ship and did the same. It was necessary to pull along the shore only when the ship ran aground. That is, the episode depicted by Repin is an isolated case.

The same exception to the rule can be called the section of road shown in the picture. Towpath – coastal strip, along which the barge haulers moved, by order of Emperor Paul, was not built up with buildings and fences, but there were plenty of bushes, stones and swampy places there. The deserted and flat coast depicted by Repin is an ideal section of the route, of which in reality there were few.

The painting “Barge Haulers on the Volga” was painted in 1870-1873, when steamships replaced barge sailing boats, and the need for barge haulers’ labor disappeared. Back in mid-19th V. the labor of barge haulers began to be replaced by machine traction. That is, at that time the theme of the picture could no longer be called relevant. That’s why a scandal erupted when Repin’s “Burlakov” was sent to the World Exhibition in Vienna in 1873. Russian minister Railways was indignant: “Well, what is the difficult reason that compelled you to paint this ridiculous picture? But I have already reduced this antediluvian method of transport to zero and soon there will be no mention of it!” However, Repin himself was patronized Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, who not only spoke approvingly of the artist’s work, but even purchased it for his personal collection.

Repin wrote “Burlakov” at the age of 29, finishing his studies at the Academy of Arts. At the end of the 1860s. he went on sketches to Ust-Izhora, where he was amazed by the artel of barge haulers he saw on the shore. To find out more about the characters that interested him, Repin settled for the summer in Samara region. His research cannot be called serious, as he himself admitted: “I must admit frankly that I was not at all interested in the question of everyday life and the social structure of contracts between barge haulers and their owners; I questioned them only to give some seriousness to my case. To tell the truth, I even absentmindedly listened to some story or detail about their relationship with the owners and these bloodsucking boys.”

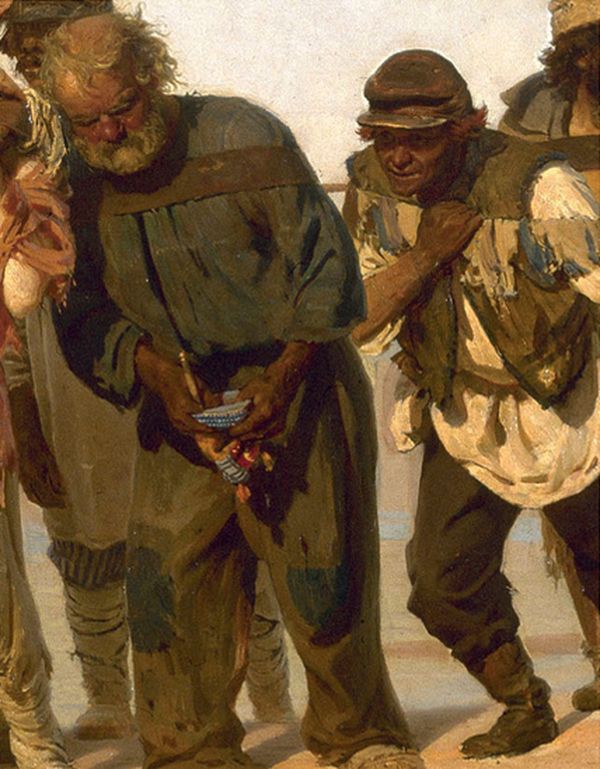

I. Repin. Barge haulers on the Volga. Fragment: *bump* was walking ahead, next to him were *bumps*

Nevertheless, “Barge Haulers on the Volga” quite accurately reproduces the hierarchy of hired workers: in the front strap there was always a strong and experienced barge hauler, called a “shishka” - he established the rhythm of movement. Behind him were the “bonded”, who worked for grub, since they managed to squander all their wages at the beginning of the journey; they were urged on by the “zealous”. To keep everyone in step, the big man would sing songs or simply shout out words. In the role of the “big shot,” Repin portrayed Kanin, a stripped-down priest who joined the barge haulers. The artist met him on the Volga.

I. Repin. Barge haulers on the Volga. Fragment: on the left – *bonded*, on the right – cook Larka

Despite the existence real prototypes, in academic circles “Burlakov” was nicknamed “the greatest profanation of art”, “the sober truth of miserable reality.” Journalists wrote that Repin embodied “thin ideas transferred onto canvas from newspaper articles... from which realists draw their inspiration.” At the exhibition in Vienna, many also greeted the painting with bewilderment. F. Dostoevsky was one of the first to appreciate the painting, whose admiring reviews were later picked up by art connoisseurs.

I. Repin. Barge haulers on the Volga. Fragment: *supervisor* urging the hacks on

"Barge Haulers on the Volga" is one of the most famous paintings the great Russian artist Ilya Repin (1844-1930). The painting was created in the period 1870-1873. Art critics define the genre of this painting as naturalism with elements of critical realism.

Burlak - hired worker in Russia XVI- the beginning of the 20th century, who, walking along the shore (along the so-called towpath), pulled a river vessel against the current with the help of a towline. In the 18th-19th centuries, the main type of vessel driven by barge haulers was the bark. Burlatsky labor was seasonal. The boats were pulled along big water": spring and autumn. To fulfill the order, barge haulers united in artels. The work of a barge hauler was extremely hard and monotonous. The speed of movement depended on the strength of the tailwind or headwind. When there was a fair wind, a sail was raised on the ship (bark), which significantly accelerated movement. Songs helped the barge haulers maintain the pace of movement. One of the well-known barge haulers’ songs is “Eh, dubinushka, whoosh,” which was usually sung to coordinate the forces of the artel at one of the most difficult moments: moving the bark from its place after raising the anchor.

When Dostoevsky saw this painting by Ilya Repin “Barge Haulers on the Volga,” he was very happy that the artist had not put any social protest. In “The Diary of a Writer” Fyodor Mikhailovich noted: “... barge haulers, real barge haulers and nothing more. Not one of them shouts from the picture to the viewer: “Look how unhappy I am and to what extent you are in debt to the people!”

The first impression of the canvas is a group of exhausted people under the hot sun pulling a barge, overcoming the force of the flow of the great Russian river. There are eleven people in the gang, and each of them pulls a strap that cuts into the chest and shoulders. From the torn clothes it becomes clear that only extreme poverty can push a person into such work. Some barge haulers' shirts are so shabby that the strap simply rubbed right through them. However, people stubbornly continue to pull the ship by the rope.

If you take a closer look at the characters individually, you can see that each has their own character. Someone completely submitted hard fate, someone is philosophically calm, because they understand that the season will end, and with it the hard work. But after this the family will no longer be in need.

The composition of the picture is built as if the barge haulers are walking towards the viewer. However, the people pulling the burden do not cover each other, so you can see that one of the characters lights a cigarette while the rest take on the entire load. However, all the gang members are calm, apparently due to great fatigue. They will treat their friend with the understanding that he now needs a little rest.

The central character walks with skill. This is an elderly barge hauler, apparently the leader of the gang. He already knows exactly how to calculate his forces, so he steps evenly. Despite the heat, he is wearing thick clothes, since he knows that a light shirt will quickly wear out during such work. His gaze reflected fatigue, and even some hopelessness, but at the same time, the awareness that the person walking would still be able to overcome the road.

The then publicist Alexei Suvorin responded with numerous criticism of Repin’s work. Despite this, many colleagues and people of that time accepted the picture enthusiastically, for example Kramskoy and Stasov. Nevertheless, at the world exhibition, the painting was awarded only a bronze medal. Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich really liked the painting, who bought it for three thousand rubles.

The main canvas measures 131.5 cm by 281 cm, the painting is located in the Russian Museum in the city Saint Petersburg, the smaller canvas “Barge Haulers Wading,” 1872, size 62 cm by 97 cm, is in the Tretyakov Gallery.

1. Towpath

1. Towpath

A trampled coastal strip along which barge haulers walked. Emperor Paul forbade the construction of fences and buildings here, but that was all. Neither bushes, nor stones, nor swampy places were removed from the barge haulers’ path, so the place written by Repin can be considered an ideal section of the road.

2. Shishka - barge hauler foreman

He became a dexterous, strong and experienced person who knew many songs. In the artel that Repin captured, the big shot was the pop figure Kanin (sketches have been preserved, where the artist indicated the names of some of the characters). The foreman stood, that is, fastened his strap, in front of everyone and set the rhythm of the movement. The barge haulers took each step synchronously with their right leg, then pulling up with their left. This caused the whole artel to sway as it moved. If someone lost their step, people collided with their shoulders, and the cone gave the command “hay - straw,” resuming movement in step. Maintaining rhythm on the narrow paths over the cliffs required great skill from the foreman.

3. Podshishelnye - the closest assistants of the cones, hanging to the right and left of him. By left hand From Kanin comes Ilka the Sailor, the artel foreman who purchased provisions and gave the barge haulers their salaries. In Repin’s time it was 30 kopecks a day. For example, this is how much it cost to cross the whole of Moscow in a cab, driving from Znamenka to Lefortovo (not so little - all of Moscow in a cab, that is, a taxi). Behind the backs of the underdogs were those in need of special control.

![]()

4. “The bonded ones,” like a man with a pipe, managed to squander their wages for the entire voyage even at the beginning of the journey. Being indebted to the artel, they worked for grub and did not try very hard.

5. The cook and falcon headman (that is, responsible for the cleanliness of the latrine on the ship) was the youngest of the barge haulers - the village boy Larka. Considering his duties more than sufficient, Larka sometimes made a row and defiantly refused to pull the strap.

6. “Hack workers”

In every artel there were also simply careless people. On occasion, they were not averse to shifting someburdens on the shoulders of others

.

7. "Overseer"

The most conscientious barge haulers walked behind, urging the hacks on.

8. Inert or inflexible

Inert or inert - this was the name of the barge hauler who brought up the rear. He made sure that the line did not catch on the rocks and bushes on the shore. The inert one usually looked at his feet and rested to himself so that he could go to own rhythm. Those who were experienced but sick or weak were chosen for the inert ones.

9-10. Bark and flag

Type of barge. These were used to transport Elton salt, Caspian fish and seal oil, Ural iron and Persian goods (cotton, silk, rice, dried fruits) up the Volga. The artel was based on the weight of the loaded ship at the rate of approximately 250 poods per person. A load that is pulled up the river 11 barge haulers, weighing at least 40 tons. The order of the stripes on the flag was not taken too seriously, and was sometimes raised upside down, as here.

11 and 13. Pilot and water tanker

The pilot is the man at the helm, in fact the captain of the ship. He earns more than the entire artel combined, gives instructions to the barge haulers and maneuvers both the steering wheel and the blocks that regulate the length of the towline. Now the bark is making a turn, going around the shoal.

Vodoliv is a carpenter who caulks and repairs the ship, monitors the safety of the goods, and bears financial responsibility for them during loading and unloading. According to the contract, he does not have the right to leave the bark during the voyage and replaces the owner, leading on his behalf.

12. Becheva - a cable to which barge haulers lean. While the barge was being led along the steep yar, that is, right next to the shore, the line was pulled out about 30 meters. But the pilot loosened it, and the bark moved away from the shore. In a minute, the line will stretch like a string and the barge haulers will have to first restrain the inertia of the vessel, and then pull with all their might. At this moment, the bigwig will begin to chant: “Here we go and lead, / Right and left they intercede. / Oh once again, once again, / Once again, once again...” and so on, until the artel gets into a rhythm and moves forward.

14. The sail rose with a fair wind, then the ship sailed much easier and faster. Now the sail is removed, and the wind is headwind, so it’s harder for the barge haulers to walk and they can’t take a long step.

15. Carving on bark

Since the 16th century, it was customary to decorate Volga barks with intricate carvings. It was believed that it helps the ship rise against the current. The country's best specialists in ax work were engaged in barking. When steamships displaced wooden barges from the river in the 1870s, craftsmen scattered in search of work, and in wooden architecture Central Russia The thirty-year era of magnificent carved frames has begun. Later, carving, which required high skill, gave way to more primitive stencil cutting.

IN Western Europe(e.g. in Belgium, the Netherlands and France, but also in Italy) movement river boats with the help of manpower and draft animals, it was preserved until the thirties of the 20th century. But in Germany, the use of manpower ceased in the second half of the 19th century. There were also women's artels.

| Categories: | |

Cited

Liked: 6 users

Each of I. Repin’s works is characterized by a unique story, because he wrote them over several years. The exposition, plot, setting were carefully thought out, and many sketches were made. The artist painted watercolor sketches in which he embodied the original plan, but completely different subjects appeared in the paintings.

No exception was the canvas “Barge Haulers on the Volga,” which Repin created on the threshold of his thirtieth birthday, which later became business card masters The idea arose completely by accident, like all ingenious things.

Repin ended up in Ust-Izhora in 1868. He came there to sketch sketches for his academic subjects. Ladies in magnificent dresses and dapper gentlemen were walking along the shore of the reservoir, but on the water itself, a gang of barge haulers in tattered rags, blackened by the sun, was dragging a barge. Their haggard, tired appearance, gloomy faces and eyes sparkling with anger and hopelessness struck the artist so much that he could not think about anything else.

Barge haulers became his obsession. He drew sketches of these people climbing ashore, drew a barge separately, drew many variations of the plot, until he finally came to a single concept for the picture. After that, he communicated with many barge haulers, observed them, memorizing their gait and facial features. The first impulse was to denounce the exploitation of people, but then he found something that would make many think - the backbreaking work of man and the game of contrasts.

Take a closer look at the nature of the Volga - amber sand, grains of which sparkle in the sun, the purest blue sky with almost imperceptible clouds, crystal blue transparent water. This beauty fades in the face of eleven gray-brown, even sallow men who are pulling a huge white barge with people. Their clothes have long ceased to be such - they are rags, thoroughly soaked with sweat, rotten bast shoes and foot wraps. Their faces are no longer faces - they are just eyes and clenched lips that reflect hard and low-paid work. Their feet will get stuck in the water and sand from the unbearable weight of the barge, and the Volga will still stretch for a thousand kilometers.

They say that the barge haulers sang, but Repin’s heroes are silent, they are unable to utter a word, but can only “pull the strap.” In all art textbooks and books of Soviet times it is written that “Barge Haulers on the Volga” is the groan of the Russian people. In fact, this is silence from fatigue, when people are unable to speak. Each of them is a personality with his own destiny, about which both the artist himself and the painting tell a story. Each barge hauler is individual, he has his own character, inner world, psychology and attitude to life.

The first to go are those who were called “indigenous”, that is, they have been hauling barges for many years; they have gained experience and know all the fords of the river. First comes Kanin, a shorn priest, next to him is an overgrown barge hauler, with a beard hiding his face. Ilka’s head, walking behind the priest, is tied with a rag, and in his eyes one can read not fatigue, but wild, maddened anger. An embittered barge hauler with a cradle in his teeth seems to understand that he will have nothing but a barge in his life. The village boy in the red shirt is Larka, the only one who looks at the surroundings with surprise.

The most striking of all the images of the eleven men is Kanin. Repin, calling it “the pinnacle of the barge hauler epic,” spent a long time accumulating material for the image, copying someone’s manner of holding a strap, and someone’s facial expression. There is a mind in him, and a living and ancient one, there is wisdom and strength. Repin, which rarely happens with an artist, was delighted with this image. Kanin is the informal head of the artel, who has seen a lot in his time.

Young Larka reflects the spiritual essence of the shorn priest. This is youth itself, which is distinguished by inquisitiveness, rebellion and the desire to live. If we compare him with Kanin, then the village guy is the antipode of the barge hauler, his crooked mirror. The artist contrasted youth worldly wisdom, childlike purity - endurance, and fragility - strength and masculinity.

The semantic load of each image from a gang of barge haulers is individual. They submit to their fate, in others obvious traits of protest and anger are visible, and still others are imperturbable and simple-minded. The figure of Kanin, however, is the brightest, because it personifies the entire fusion of features of each of them. At first glance, this stocky man is the same as everyone else, but if you take a closer look at him, it seems that he knows everything that others only dream of - a better life.

Compositionally, the canvas is elongated in width - this technique allows Repin to arrange the figures of workers along the shore, choosing the most typical and dramatic images. In the foreground of the picture - main character, the middle of the composition consists of images that reveal it. The background of the picture is the white barge itself with two fuzzy figures. As you know, this car is a motor vehicle, but to save fuel it was used at that time burlatsky labor. A flag flies on the mast of the ship Russian Empire, the soullessness of which the artist criticized.

The rhythm of the canvas consists of bowed and raised heads and figures of people - this is how the nature of their fate is more deeply felt and revealed. The tension of “Barge Haulers on the Volga” is visible in the pose of their bodies, the tension of the strap and the weight of the barge.

The painting was first exhibited in 1873. It instantly became a cult - the images of barge haulers made the human conscience wake up and realize that the entire empire was built on bones. Repin gained fame, but he became a kind of dissident of his time, and the rector of the institution where he studied said that this painting refutes the entire value of art.

If you remember that before that they painted landscapes, portraits of artists, illustrations for literary works and Italian scenes, it will immediately become clear that the use folk images it was bad manners.

When the painting was exhibited in Vienna, visitors were surprised that such labor was practiced in Russia, but barge haulage itself was abolished only at the beginning of the 20th century.

What is Ilya Repin’s painting “Barge Haulers on the Volga” about and why every detail is important.

1. Towpath

A trampled coastal strip along which barge haulers walked. Emperor Paul forbade the construction of fences and buildings here, but that was all. Neither bushes, nor stones, nor swampy places were removed from the barge haulers’ path, so the place written by Repin can be considered an ideal section of the road.

2. Shishka - foreman of barge haulers

He became a dexterous, strong and experienced person who knew many songs. In the artel that Repin captured, the big shot was the pop figure Kanin (sketches have been preserved, where the artist indicated the names of some of the characters). The foreman stood, that is, fastened his strap, in front of everyone and set the rhythm of the movement. The barge haulers took each step synchronously with their right leg, then pulling up with their left. This caused the whole artel to sway as it moved. If someone lost their step, people collided with their shoulders, and the cone gave the command “hay - straw,” resuming movement in step. Maintaining rhythm on the narrow paths over the cliffs required great skill from the foreman.

3. Podshishelnye - the closest assistants of the cone, hanging to the right and left of him. On the left hand of Kanin is Ilka the Sailor, the artel foreman who purchased provisions and gave the barge haulers their salaries. In Repin’s time it was small - 30 kopecks a day. For example, this is how much it cost to cross the whole of Moscow in a cab, driving from Znamenka to Lefortovo. Behind the backs of the underdogs were those in need of special control.

You just need to understand that 30 kopecks for travel from end to end of Moscow should not be compared with the cost public transport(which didn’t exist then), but with a taxi. A pound of beef (about half a kilo), at the same time, cost the same 18 kopecks. That is, men could afford a piece of meat EVERY DAY. And this is far from the cheapest product available in the diet of Russian people at that time. For the cost of travel from end to end of Moscow by taxi, in many regions today you can live for 2-3 days.

4. The “bonded”, like a man with a pipe, even at the beginning of the journey managed to squander their salary for the entire voyage. Being indebted to the artel, they worked for grub and did not try very hard.

5. The cook and falcon headman (that is, responsible for the cleanliness of the latrine on the ship) was the youngest of the barge haulers - the village boy Larka, who experienced real hazing. Considering his duties to be more than sufficient, Larka sometimes made trouble and defiantly refused to pull the burden.

6. "Hack workers"

In every artel there were simply careless people, like this man with a tobacco pouch. On occasion, they were not averse to shifting part of the burden onto the shoulders of others.

7. "Overseer"

The most conscientious barge haulers walked behind, urging the hacks on.

8. Inert or inflexible

Inert or inert - this was the name of the barge hauler, who brought up the rear. He made sure that the line did not catch on the rocks and bushes on the shore. The inert one usually looked at his feet and rested to himself so that he could walk at his own rhythm. Those who were experienced but sick or weak were chosen for the inert ones.

9-10. Bark and flag

Type of barge. These were used to transport Elton salt, Caspian fish and seal oil, Ural iron and Persian goods (cotton, silk, rice, dried fruits) up the Volga. The artel was based on the weight of the loaded ship at the rate of approximately 250 poods per person. The cargo pulled up the river by 11 barge haulers weighs at least 40 tons.

The order of the stripes on the flag was not paid much attention to, and was often raised upside down, as here.

11 and 13. Pilot and water tanker

The pilot is the man at the helm, in fact the captain of the ship. He earns more than the entire artel combined, gives instructions to the barge haulers and maneuvers both the steering wheel and the blocks that regulate the length of the towline. Now the bark is making a turn, going around the shoal.

Vodoliv is a carpenter who caulks and repairs the ship, monitors the safety of the goods, and bears financial responsibility for them during loading and unloading. According to the contract, he does not have the right to leave the bark during the voyage and replaces the owner, leading on his behalf.

12. Becheva - a cable to which barge haulers lean. While the barge was being led along the steep yar, that is, right next to the shore, the line was pulled out about 30 meters. But the pilot loosened it, and the bark moved away from the shore. In a minute, the line will stretch like a string and the barge haulers will have to first restrain the inertia of the vessel, and then pull with all their might. At this moment, the bigwig will begin to chant: “Here we go and lead, / Right and left they intercede. / Oh once again, once again, / Once again, once again. . . ", etc., until the artel gets into a rhythm and moves forward.

14. The sail rose with a fair wind, then the ship sailed much easier and faster. Now the sail is removed, and the wind is headwind, so it’s harder for the barge haulers to walk and they can’t take a long step.

15. Carving on bark

Since the 16th century, it was customary to decorate Volga barks with intricate carvings. It was believed that it helps the ship rise against the current. The country's best specialists in ax work were engaged in barking. When steamships displaced wooden barges from the river in the 1870s, craftsmen scattered in search of work, and a thirty-year era of magnificent carved frames began in the wooden architecture of Central Russia. Later, carving, which required high skill, gave way to more primitive stencil cutting.