Alexander II (1818–1881) went after the bear with a spear and hated Moscow. Nicholas I (1825–1855) was the only non-smoking Russian Emperor. Alexander III

The last Russian Emperor Nicholas II (1868–1918) and Prince Nicholas of Greece (1872–1938)

Photo: State Archives of the Russian Federation, ca. 1899–1900

Alexander II (1818–1881) went after the bear with a spear and hated Moscow. Nicholas I (1825–1855) was the only non-smoking Russian Emperor. Alexander III (1881–1894) did not disdain “mater”, but he was the first of the tsars to address his subordinates as “you.” And Nicholas II (1868–1918) wrote down and carefully sketched absolutely all the jewelry that was ever given to him.

Of all the Emperors, only Nicholas I did not smoke. Accordingly, the people working with him also did not smoke. And those who worked with those who worked did not smoke either. Those who worked with those who worked with those who worked did not smoke either. And so on. Therefore, smokers were treated very poorly throughout his reign. Smoking was prohibited even on the streets and squares. The rest of the emperors smoked. It is curious that Empresses Catherine and Elizabeth loved snuff. They were both right-handed, but they always took tobacco from snuff boxes with their left hand - tobacco turned the skin on their hand yellow, and therefore the left hand is yellow and smells of tobacco, and the right hand is for kissing.

This is a snuff box from the erotic collection of Nicholas I:

By the way, he is very happily married and began collecting an erotic collection as a hobby. This is not surprising. Each of our subsequent emperors continued to collect this collection. And Alexander II, and Alexander III, and Nicholas II.

Passionate hunter Alexander II killed his first bear at the age of 19. And not with a gun, but with a spear. He threw his hat over the bear and forward. The collection of the Gatchina Arsenal contains the spears with which Alexander went to hunt the bear.

The diary entries about the hunting of Nicholas II are surprising. It felt like he had some kind of complex that he was breaking down during the hunt. Here are some entries.

January 11, 1904: “The duck hunt was very successful - a total of 879 were killed.”

Buchanan recalled that during one of his hunts, Nicholas II killed 1,400 pheasants.

In 1900, in Belovezhskaya Pushcha, Nikolai killed 41 bison. And he went hunting to Belovezhskaya Pushcha every year. It is interesting that the German Emperor Wilhelm II persistently asked Alexander III to go hunting in Belovezhskaya Pushcha, but Alexander never took Wilhelm with him. Alexander had a strong dislike for William.

The photo shows Nicholas II after his next deer hunt. It's not that simple there either. It was forbidden to shoot deer and those with less than 10 branches in the antlers.

When at the beginning of the First World War in Russia they began to intern the Germans who were in the Russian service of the Ministry of the Imperial Household, they took all but two. One of these two lucky ones was Nikolai's hunter and royal huntsman Vladimir Romanovich Dits.

Alexander III always emphasized his Russianness. Addressing everyone as “you,” he did not disdain using Russian language to speed up his subordinates or express his feelings to them in Russian. When communicating with his subordinates, he had no posture - he was very simple, like a simple Russian person. Then this beard is his. And he himself liked to be Russian. Although he had no illusions on this score. His mother, grandmother and great-grandmother were German princesses. They say that when he read the “Notes” of Catherine II and learned from them that the father of his great-grandfather Paul I was not Peter III, but an ordinary Russian nobleman, he was very happy. Peter the Third was a Holstein-Gottorp prince, and a Russian nobleman was still Russian - this greatly increased his, Alexander’s, share of Russian blood. Hence the joy.

Alexander I addressed his subordinates using “you,” but this was due to the fact that at court, they mostly communicated in French; when they switched to Russian, they invariably switched to “you.” Nicholas I said “you” to everyone. Alexander II and his brothers treated their subordinates in the same way. Subordinates were very afraid when Alexander II addressed them as “you” - this meant an official tone and the beginning of a scolding and thunderstorm. The first king who began to say “you” to his subordinates was Alexander III.

Wha-oh?? Me - in this? Single breasted? What are you talking about? Don’t you know that no one fights in single-breasted clothes anymore? Ugliness! War is at our doorstep, but we are not ready! No, we are not ready for war! ©

On the New Year, 1845, Nicholas I gave his 22-year-old daughter, Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna, a royal gift - she became the chief of the 3rd Elisavetgrad Hussar Regiment. The bomb was there - in the uniform that Olga was now supposed to wear on such occasions. The fact is, like any woman, Olga wanted it to be beautiful, but her father wanted it to be according to the Charter. Olga didn’t want embroidered chakchirs, didn’t want a saber, didn’t want trousers, but wanted a skirt. The conflict was serious. Women are very flexible. They can forgive, forget, sacrifice and, in general, whatever they want, but they cannot wear clothes that they do not like. Olga did not like the saber - a completely understandable desire of a 22-year-old girl. A compromise was found in an exchange: Nikolai agreed to a skirt. Olga was so happy that she agreed to the saber.

Alexander II was rapidly losing his reputation because of this second marriage to Ekaterina Dolgoruka. They got married when forty days had not yet passed since the death of his first wife. And she was not a match for him, and stupid, and by calculation on her part, and much, much more. Relatives, society, those closest to him - everyone began to turn away from him because of this. The most radical options were considered by hotheads. Why did He marry her??? It turns out that he promised to marry her in front of the icon.

His two youngest sons, Grand Dukes Nicholas and Mikhail, were sent by their father, Nicholas I, to the front in the Crimean War. Since they were sent to the front not for show, but to inspire the soldiers, things were very real there - bullets whistled and shells exploded. The guys really fought there. Shoulder to shoulder with grown men. Nikolai was 23 years old at that time, Mikhail was 21.

Alexander II hated Moscow. Despite the fact that he himself was born in it - in the Chudov Monastery - he did not love it and could not stand it. I tried to leave it as quickly as possible and return as often as possible. I'm trying to imagine myself in his place in this sense. It’s not about hating Moscow (:-)), but about hating my hometown, the city where I was born - St. Petersburg. It doesn’t turn out very well and it’s not clear how this could be.

Alexander III was just born in St. Petersburg. But he also said that he hated his hometown - St. Petersburg. The happiest time of the year for him was Easter, when they left for Moscow. He loved Moscow very much. I enjoyed going there and didn’t want to go back. He didn’t even live in St. Petersburg - he and his family lived in Gatchina. But this is more likely due to the fact that in big St. Petersburg he could easily be killed by terrorists, like his father, and in small Gatchina this was impossible to do, but he left St. Petersburg as soon as he moved away from his dying father.

The children of the kings learned foreign languages in large numbers. They spoke to their relatives, monarchs and princely houses of Europe without translators. Plus the wife's parents, mother-in-law and father-in-law, with whom it is also desirable in Danish, like Alexander III. Therefore, teaching children foreign languages was very intensive. At the request of Empress Maria Feodorovna, in 1856, Chancellor and Minister of Foreign Affairs Gorchakov prepared a memorandum on the education of the Grand Dukes. Regarding foreign languages, Gorchakov believed that the Emperor’s children should be taught Russian, then French and German. Gorchakov especially noted that there is no need to teach children English - no one speaks it in Europe anyway. Now it would be so! We, Francophiles, would rejoice :-)

Nicholas I was the first to speak Russian at the Court. Under Alexander II, French returned, but even with him his son, future Alexander III, but for now Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich spoke Russian. Alexander III emphasized his Russianness in every possible way. He even couldn’t stand the Grand Duchess Ekaterina Mikhailovna because she spoke Russian very poorly, with a monstrous accent - the wives of the Grand Dukes, mostly German princesses, were forced to learn this Russian at their wedding age, and therefore who he learned it well, and some, like Ekaterina Mikhailovna, poorly. The Tsar did not like her very much and called her children “poodles.”

This is Alexander III. He is in almost all photographs with a big beard. His father Alexander II long before Turkish war By his Decree he forbade the wearing of beards - he did not like them. And no one wore it. Look at the portraits of nobles and officials of that time - not a single one has a beard. Mustaches, sideburns - please, but the chin is bare. But the Russian-Turkish war began and for the duration of the war the Tsar allows those who wish to grow a beard. And everyone was released. Including the future Alexander III. However, immediately after the war, Alexander II again forbade wearing beards - “to get yourself in order,” as Alexander writes in the Decree. And again everything was shaved off. Only one person did not shave - his son Alexander Alexandrovich. So I always wore a beard after that. And when he was the Grand Duke and after, when he became a king. To put it mildly, the relationship between father and son was rather cool. They didn't get along very well - father and son.

Nicholas II manically led quite detailed records. Diaries and albums are sometimes full of such completely unimportant details that it seems that the author is sick. This is how I see the famous “Jewelry Album” of Nicholas II. In it he wrote down absolutely all the jewelry that had ever been given to him. Not only did he write who gave it, but he also carefully sketched what was given to him. 305 entries. Go crazy. Here, for example, is one of the album pages. The jewelry that will interest you most was given to Nikolai by Alix:

Russian history provides answers to many questions, but it contains even more secrets. Particularly interesting are the mysteries that the autocrats left behind. They knew how to keep secrets.

Was there Rurik?

This main Russian question, along with “Who is to blame?” and “What should I do?” A question that we are unlikely to ever get an answer to.

The personality of Rurik (d. B 879) to this day causes a lot of controversy, even to the point of denying his existence. For many famous Varangian nothing more than a semi-mythical figure. This is understandable. IN historiography XIX– In the 20th century, the Norman theory was criticized, since domestic science could not bear the idea of the inability of the Slavs to create their own state.

Modern historians are more loyal to the Norman theory. Thus, academician Boris Rybakov puts forward a hypothesis that in one of the raids on the Slavic lands, Rurik’s squad captured Novgorod, although another historian, Igor Froyanov, supports the peaceful version of “calling the Varangians” to rule.

The problem is that the image of Rurik lacks specificity. According to some sources, he could be the Danish Viking Rorik of Jutland, according to others, the Swede Eirik Emundarson, who raided the lands of the Balts.

There is also a Slavic version of the origin of Rurik. His name is associated with the word “Rerek” (or “Rarog”), which in the Slavic tribe of Obodrits meant falcon. And, indeed, during excavations of early settlements of the Rurik dynasty, many images of this bird were found.

Secret seal of Ivan III

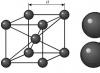

The double-headed eagle in Russia first appeared on state seal Grand Duke Ivan III in 1497. Historians almost categorically assert that the eagle appeared in Rus' with the light hand of Sophia Paleolog, the latter’s niece Byzantine emperor and the wife of Ivan III.

But why Grand Duke decided to use the eagle only two decades later, no one explains. It is interesting that precisely at the same time in Western Europe double headed eagle became fashionable among alchemists. Authors of alchemical works put the eagle on their books as a sign of quality.

The double-headed eagle meant that the author received Philosopher's Stone, capable of turning metals into gold. The fact that Ivan III gathered around him foreign architects, engineers, and doctors, who probably practiced then fashionable alchemy, indirectly proves that the tsar had an idea of the essence of the “feathered” symbol.

Death of the son of Ivan the Terrible

Moscow is the capital of Russia, the Volga flows into the Caspian Sea, and Ivan the Terrible killed his son. The main evidence is Repin's painting... Seriously, Ivan Vasilyevich's murder of his heir is a very controversial fact. So, in 1963, the tombs of Ivan the Terrible and his son were opened in the Archangel Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. Research has made it possible to claim that Tsarevich John was poisoned. The poison content in his remains is many times higher than permissible norm. Interestingly, the same poison was found in the bones of Ivan Vasilyevich. Scientists have concluded that the royal family was the victim of poisoners for several decades.

Ivan the Terrible did not kill his son. This is precisely the version adhered to, for example, by the Chief Prosecutor of the Holy Synod, Konstantin Pobedonostsev. Seeing Repin’s famous painting at the exhibition, he was outraged and wrote to Emperor Alexander III: “The painting cannot be called historical, since this moment... is purely fantastic.” The version of the murder was based on the stories of the papal legate Antonio Possevino, who can hardly be called a disinterested person.

Dmitry with the prefix "false"

We have already accepted that False Dmitry I is the fugitive monk Grishka Otrepiev. The idea that “it was easier to save than to fake Demetrius” was expressed by the famous Russian historian Nikolai Kostomarov. And indeed, it looks very surreal that at first Dmitry (with the prefix “false”) was recognized by his own mother, princes, and boyars in front of all the honest people, and after some time, everyone suddenly saw the light.

The pathological nature of the situation is added by the fact that the prince himself was completely convinced of his naturalness, as his contemporaries wrote about. Either this is schizophrenia, or he had reasons. It is not possible, at least today, to check the “originality” of Tsar Dmitry Ivanovich. Therefore, we are waiting for the invention of the time machine and, just in case, we keep a fig in our pocket - about the Impostor.

“But the king is not real!”

Many Russian boyars were of this conviction after the return of Peter I from a 15-month tour of Europe. And the point here was not only in the new royal “outfit”. Particularly attentive persons found inconsistencies physiological properties: firstly, the king has grown significantly, and, secondly, his facial features have changed, and, thirdly, the size of his legs has become much smaller.

Rumors spread throughout Muscovy about the replacement of the sovereign. According to one version, Peter was “put into the wall”, and instead of him, an impostor with a similar face was sent to Rus'. According to another, “the Germans put the Tsar in a barrel and sent it to sea.” Adding fuel to the fire was the fact that Peter, who returned from Europe, began a large-scale destruction of “ancient Russian antiquity.” It is interesting that there were versions that the Tsar was replaced in infancy: “The Tsar is not of Russian breed, and not the son of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich; taken in infancy from German settlement, from a foreigner on exchange. The queen gave birth to a princess, and instead of the princess they took him, the sovereign, and gave the princess instead of him.”

Pavel I Saltykov

Emperor Paul I unwittingly continued the tradition of generating rumors around the House of Romanov. Immediately after the birth of the heir, rumors spread throughout the court, and then throughout Russia, that the real father of Paul I was not Peter III, but the first favorite Grand Duchess Ekaterina Alekseevna, Count Sergei Vasilievich Saltykov. This was indirectly confirmed by Catherine II, who in her memoirs recalled how Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, so that the dynasty would not fade away, ordered the wife of her heir to give birth to a child, regardless of who his genetic father would be. There is also a folk legend about the birth of Paul I: according to it, Catherine gave birth to a dead child from Peter, and he was replaced by a certain “Chukhon” boy.

His Majesty Fyodor Kuzmich

The “tabloid” theme of Paul I was continued by his son, Alexander I. Firstly, he became a direct participant in the murder of his father. Well, secondly, and this main legend, Alexander left the royal throne by falsifying own death, and went to wander around Rus' under the name of Fyodor Kuzmich.

There are several indirect confirmations of this legend. Thus, witnesses concluded that on his deathbed Alexander was categorically unlike himself. In addition, for unclear reasons, Empress Elizaveta Alekseevna, the Tsar's wife, did not participate in the funeral ceremony. The famous Russian lawyer Anatoly Koni conducted thorough comparative studies handwritings of the emperor and Fyodor Kuzmich and came to the conclusion that “the letters of the emperor and the notes of the wanderer were written by the hand of the same person.”

Power does not have the best effect on people.

Absolute power is especially corrupting.

This is clearly seen in the example of Russian tsars and queens, who had unusual hobbies and got into funny stories.

Peter the Great and Charles

Emperor Peter I is one of the most eccentric Russian rulers

Emperor Peter I loved dwarfs from childhood, and during his reign it was common practice for noble nobles to keep Lilliputians as jesters. However, Peter himself took this hobby to the extreme. From time to time he ordered a naked midget to be baked in a pie, so that in the middle of dinner he would suddenly jump out of the pie to the fear of the guests and to the amusement of the emperor.

Peter I arranged the weddings of the Lilliputians

Peter even tried to breed dwarfs. For the wedding of the Tsar's jester Yakim Volkov and the dwarf who served the Tsarina, more than seventy dwarfs, mostly poor peasants, were brought from all over Russia. They were dressed in specially tailored clothes of European styles, drunk with wine and forced to dance to entertain those present. The emperor was very pleased.

Catherine the Second and the collection of erotica

According to rumors, the office, furnished with custom-made furniture with frivolous carvings, adjoined the empress’s private chambers in the Gatchina Palace. The room was filled with the finest examples of erotic painting and sculpture, some of which came from excavations in Pompeii.

Catherine II collected a large collection of erotic sculptures

According to the official version, the collection was destroyed in 1950. A catalog issued in the 1930s and several photographs taken by German officers during World War II have been preserved. There is a version that the secret office was located not in Gatchina, but in Peterhof, and can still be found.

Ivan the Terrible and the fake Tsar

In 1575, Ivan IV unexpectedly abdicated the throne and declared that from now on he would become a simple boyar, Vladimir of Moscow. He handed over the throne to the baptized Tatar Simeon Bekbulatovich, direct descendant Genghis Khan. Simeon was officially crowned king in the Assumption Cathedral, and Ivan settled in Petrovka. From time to time, the retired tsar sent petitions to Simeon, signed by Ivanets Vasiliev.

Ivan the Terrible abdicated the throne “for show”

During the 11 months of Simeon's reign, Ivan, with his hands, returned to the treasury all the lands previously granted to monasteries and boyars, and in August 1576 he just as suddenly took the throne again. Simeon's relations with subsequent kings were extremely unhappy. Boris Godunov ordered him to be blinded, False Dmitry I forced him to go to a monastery, Vasily Shuisky exiled him to Solovki. Simeon’s burial place is located under the foundation of the cultural center of the Likhachev Plant, on the site where the necropolis of the Simonov Monastery was once located.

Alexander II and his sense of humor

One day, Alexander II, passing a small provincial town, decided to attend a church service. The temple was overcrowded. The chief of the local police, seeing the emperor, began to clear the way for him among the parishioners with blows of his fists and shouts: “With respect! With trepidation! Alexander, having heard the words of the police chief, laughed and said that he now understands how exactly in Russia they teach humility and respect. Another ironic phrase attributed to Alexander II: “It is not difficult to rule Russia, but it is pointless.”

Alexander II had a specific sense of humor

Alexander III and genealogy

The penultimate emperor, nicknamed the Peacemaker (under him, the Russian Empire did not participate in wars), loved everything Russian, wore a thick beard and had difficulty accepting the fact that the royal family actually consisted of Germans. Soon after the coronation, Alexander gathered his closest courtiers and asked them who the real father of Paul I was. The historiographer Barskov replied that, most likely, Alexander's great-great-grandfather was Count Sergei Vasilyevich Saltykov. "God bless!" - the emperor exclaimed, crossing himself. - “So, I have at least a little Russian blood in me!”

Alexander III was a consistent Slavophile

Elizaveta Petrovna and women's pride

Possessing a naturally gentle character, the daughter of Peter the Great did not make concessions only in matters of fashion and beauty. No one was allowed to copy the style of clothing and hairstyle of the Empress or appear at the reception in an outfit that was more luxurious than Elizabeth’s dress. At one of the balls, the empress personally cut off the ribbons and hairpins of the wife of Chief Chamberlain Naryshkin, along with the hair, under the pretext that her hairstyle vaguely resembled the royal one.

Elizaveta Petrovna loved balls and dresses most of all

One day, after a ball, the court hairdresser was unable to wash and comb Elizabeth’s hair, which was sticky from hairdressing potions. The Empress was forced to cut her hair. Immediately, the ladies of the court were ordered to shave their heads and wear black wigs until the order was rescinded. Only the future Catherine II, who had recently suffered an illness and lost her hair during the illness, avoided shaving her head. Moscow ladies were allowed not to shave their heads, provided that they hide their hairstyles under black wigs.

Paul I and official zeal

Since childhood, Pavel Petrovich had a passion for strict order, military uniform and maneuvers. Alexander Suvorov, according to rumors, was removed from command of the army due to statements about the inappropriateness of a German powdered wig and uncomfortable boots with buckles on a Russian soldier. One day Paul conducted a mock siege of a fortress, the defenders of which were ordered to hold out by all means until noon.

Paul I spent a lot of time in amusing fights

Two hours before the end of the exercises, the emperor, along with the regiments besieging the fortress, was caught in a heavy downpour. The commandant of the fortress was ordered to immediately open the gates and let Paul in, but he flatly refused to carry out the order. The Emperor was soaked through. Exactly at twelve o'clock the gates opened, and Pavel, bursting into the fortress in anger, attacked the commandant with reproaches.

Paul I built his residence, the Engineering Castle, as a fortress

He calmly showed the emperor the order signed in his own hand. Pavel had no choice but to praise the colonel for his diligence and discipline. The commandant immediately received the rank of major general and was sent to stand guard in the continuing rain.

Alexander I and honesty

IN recent years Alexander the First was a very God-fearing person. On Christmas Eve, while making a pilgrimage, the emperor stopped briefly at the post station. Entering the station superintendent's hut, Alexander saw the Bible on the table and asked how often the superintendent reads it.

There is a legend that Alexander I did not die, but went to a monastery under the name of Elder Fyodor Kuzmich

Seeing the book in the same place, the emperor again asked the caretaker if he had read the book since they saw each other. The caretaker again warmly assured him that he had read it more than once. Alexander leafed through the Bible - the banknotes were in place. He chided the caretaker for deception and ordered the money to be distributed to the orphans.

What if the character Ivan the Terrible wasn’t so bad, since he looked at the starry sky on dark evenings? A Lenin was not such a bore, since he loved to ride his bike down the mountain at speed? What else were our rulers interested in?

Collage AiF

1. Yaroslav the Wise (ca. 978-1054)

Yaroslav is called Wise not only because of his deeds, but also because of his hobbies. The prince loved collecting books. During his life he collected a huge library, and most of Yaroslav was able to read the books. From books he independently learned foreign languages.

2. Ivan the Terrible (1530-1584)

Ivan the Terrible was not only interested in chopping heads. In his free time from menacing activities, the king studied the starry sky and played chess. Sometimes the ruler invited people to play at the chessboard Malyuta Skuratova. But the game, as a rule, ended quickly. Malyuta pretended to be interested and tried to lose. They say that the formidable king died while sitting at the chessboard.

3. Peter I (1672-1725)

Peter I had irrepressible energy. He spent it not only on the transformation of Rus', but also on his hobbies. The king made watches, worked on a lathe, did carpentry, planted trees, and loved to tinker with doctors on a training corpse.

When he came across living people with rotten teeth, despite their pleas, he pulled out their diseased teeth. Peter was also interested in collecting. He had a huge collection of coins. But the autocrat could not cope with weaving bast shoes. He was taught by the best bast workers, but Peter never mastered the bast.

4. Peter III (1728-1762)

Peter III was not a genius, and therefore his hobbies were appropriate. Even as an adult, the king loved to play with soldiers. He spent days, and sometimes nights, playing toy fights, reenacting bloody battles in separate room, which was completely filled with soldiers. One day the king deployed his toy troops and went away. When he returned, he noticed that three soldiers made of starch had become disabled during this time - their limbs had been chewed off by a rat. Peter III, like a true commander, rushed to the defense of his subordinates, he demanded that the rodent be caught and... hanged. Over time, Peter III added another passion to his passion for soldiers - drinking.

5. Nicholas I (1796-1855)

Nicholas I had an amazing non-royal hobby. It turned out that the tsar was... a designer at heart. He often, sitting at his desk, drew military uniforms and even, together with seamstresses, improved ready-made clothes. Nicholas I obliged not only military personnel, but also “civilian” courtiers to wear their uniforms.

6. Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924)

Vladimir Ilyich loved transport. His first passion was bicycles. The leader of the proletariat could drive for hours through the mountains, streets, parks, and country roads. One day, Lenin’s bike ride in the outskirts of Paris did not go well. “I was traveling from Juvisy,” Ilyich recalled. - And the car crushed my bicycle... The public helped me write down the number... I recognized the owner of the car (Viscount, damn him!) and now I’m suing him through a lawyer. I hope to win." And he still won! In addition to bicycles, Ilyich respected good cars, and preferred French brands. Another hobby of Lenin almost cost him his life. In exile, Lenin occupied the long days and evenings with hunting. Moreover, Ilyich hunted not for food, but driven by the passion of sport. So, one day he killed several dozen hares, loaded them into a boat and went to show off to Nadezhda Konstantinovna. But the boat almost sank on the way from overload.

7. Yuri Andropov (1914-1984)

Despite his closed nature and gloomy appearance, General Secretary Yuri Andropov was a romantic at heart and wrote poetry. His creations were sometimes sad and lyrical, and when the Secretary General was having fun, he could add humor to his quatrains. Sometimes Andropov could play pranks - in his notes you can find obscene epigrams and ditties. Literary scholars believe that the Secretary General chose unusual rhymes. When Andropov was appointed to work in the KGB, he immediately wrote a poem about it: “It is known: many Ka Ge Be, as they say, “don’t like it.” And I would have gone to work in this house, probably with difficulty, if the Hungarian sad lesson had not happened for the future.”

Early morning found the sovereign in Krestovaya, in which the prayer iconostasis, all lined with icons, richly decorated with gold, pearls and expensive stones, had long been illuminated by many lamps and wax candles, glowing in almost every image. The Emperor usually got up at four in the morning.

The bedmaster, with the assistance of sleeping bags and attorneys, * handed over the dress to the sovereign and put away (dressed) it.

Having washed, the sovereign immediately went out to Krestovaya, where the confessor or the priest of the cross and the clerks of the cross were waiting for him. The confessor or priest of the cross blessed the sovereign with a cross, placing it on his forehead and cheeks, at which the sovereign venerated the cross and then began the morning prayer, at the same time one of the clerks of the cross placed on the analogue in front of the iconostasis an image of the saint whose memory was celebrated that day. After completing the prayer, which lasted about a quarter of an hour, the sovereign venerated this icon, and the confessor sprinkled him with holy water.

The holy water that was used on this occasion was sometimes brought from very distant places, from monasteries and churches glorified by miraculous icons. This water was called “festive” because it was consecrated on temple holidays, celebrated in memory of those saints in whose name the temples were built. Almost every monastery and even many parish churches, upon the celebration of such a celebration, delivered a festive shrine, an icon of the holiday, a prosphora and St. water in wax, in a wax vessel, to the royal palace, where the messengers presented it personally to the sovereign himself. Sometimes this shrine was presented at the exit of the sovereign in churches, during pilgrimage. Thus, the holiday water was not depleted all year round, and the morning prayers of the sovereign were almost always accompanied by the sprinkling of holy water at a recent consecration in some distant or near monastery.

After the prayer, the clerk of the cross read a spiritual word: a teaching, from a special collection of words distributed for reading every day for the whole year. These collections were known under the names of Zlatoust and Zlatostruev. They were compiled from the teachings of the Church Fathers and mainly John Chrysostom, which is why they were called Chrysostom.

Having finished the morning prayer of the cross, the sovereign, if he was resting especially, would send a neighbor to the queen in the mansion to ask her about her health, how was she resting? then he himself went out to greet her in her Antechamber or Dining Room. After that, they listened together in one of the high churches to matins, and sometimes early mass.

Meanwhile, in the morning, early in the morning, all the boyars, Duma and close people gathered in the palace - “to strike the sovereign with their foreheads and be present in the Tsar’s Duma. They usually gathered in the Antechamber, where they awaited the royal exit from the inner chamber or Room. Some, who enjoyed the special power of attorney of the sovereign, waited for the time and entered the Room. Seeing the bright royal eyes in the church, either during the service, or in the rooms, depending on what time they arrived, they always bowed to the ground before the sovereign, even several times. The sovereign at that time, if he stood or sat wearing a hat, then, in spite of their boyar worship, he never took off his hat. For the special mercy shown to the sovereign, the boyars bowed to him in the ground up to thirty times in a row.

So, touched by the royal favor, the great governor, Prince Trubetskoy, on vacation on the Polish campaign, in 1654, when the sovereign, saying goodbye to him, hugged him, bowed to the ground thirty times before the sovereign.

Having greeted the boyars and talked about business, the sovereign, accompanied by the entire assembled boyars, walked, at about nine o'clock, to late mass in one of the court churches. If that day was a holiday, then the exit was made to the cathedral or to the holiday, that is, to a temple or monastery built in memory of the celebrated saint. On general church holidays and celebrations, the sovereign was always present at all rites and ceremonies. Therefore, exits in these cases were much more solemn.

The mass lasted two hours. Hardly anyone was as committed to pilgrimage and to the performance of all church rites, services, and prayers as the kings. One foreigner tells about Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich that during Lent he stood in church for five or six hours at a time, sometimes making a thousand prostrations, and on major holidays, one and a half thousand.

After mass, in the Room on ordinary days, the sovereign listened to reports, petitions and generally dealt with current affairs. The chiefs of the Orders came in with reports and read them themselves before the sovereign. The Duma clerk reported the petitions brought into the Room and noted the decisions. The boyars present in the Room did not dare sit down during the hearing. If they were tired of standing, they went out to rest, sit in the Antechamber or in the vestibule, and sometimes on the platform in front of the royal mansions.

When, especially on Fridays, the Tsar opened an ordinary seat with the boyars, or a meeting of the Duma, the boyars sat on benches, at a distance from the Tsar, the boyars under the boyars, one under the other, the Duma nobles also, who were lower in breed than whom, and not in service, i.e. That is, not according to the seniority of the award to the rank, so that some, even today, awarded, for example, from among the boyars, were seated according to their breed, higher than all those boyars who were below his breed, even if they were gray-haired old men. The Duma clerks usually stood, but at other times, especially if the sitting with the boyars lasted a long time, the sovereign ordered them to sit down.

The meeting and hearing of cases in the Room ended at about twelve o'clock in the morning. The boyars, having struck the sovereign with their foreheads, went home, and the sovereign went to the table for food or dinner, to which he sometimes invited some of the boyars, the most respected and closest: but for the most part on ordinary days, when there were no festive or other ceremonial tables, which, according to custom, called on the sovereign to share a meal and feast in the circle of the boyars and all other ranks, he always ate with the queen. Casual tables Sometimes they were in the rooms of the sovereign, sometimes in the mansions of the queen. In both cases, they were not open to boyar and noble society. IN holidays Other members of the royal family, princes and princesses, especially older ones, were also present at these home tables. Sometimes the sovereign celebrated children's name days with a communal dinner in the royal mansions.

Such dinners were probably served on every family holiday. In 1667, on the occasion of the nationwide announcement of Tsarevich Alexei Alekseevich and, therefore, on the occasion of the greatest celebration for the queen herself, the mother of the heir, the next day, September 2, the sovereign celebrated the family table in the Upper room or in the tower and ate with the queen, with the declared heir Alexei, with the young princes Fyodor (5 years old). Simeon (2 years old) and Ivan (1 year old).

His ordinary table was not as abundant in food as the festive, embassy and other tables.

In their home life, the kings represented an example of moderation and simplicity. According to foreigners, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich was always served the simplest dishes, rye bread, a little wine, oatmeal or light beer with cinnamon butter, and sometimes only cinnamon water. But this table had no comparison with those that the sovereign kept during fasts. “During Lent, Tsar Alexei dined only three times a week, namely: on Thursday, Saturday and Sunday, on the other days he ate a piece of black bread with salt, a pickled mushroom or cucumber and drank half a glass of beer.

He ate fish only twice a day. Lent and observed all seven weeks of fasting... Apart from fasting, he did not eat anything meat on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays; in a word, not a single monk will surpass him in the severity of fasting. We can consider that he fasted for eight months a year, including six weeks of the Nativity Fast and two weeks of other fasts.” This is a foreigner speaking. Such diligent observance of fasts was an expression of the sovereign’s strict adherence to Orthodoxy, to all the statutes and rituals of the Church. The foreigner's testimony is fully confirmed by the domestic witness.

“On fasting days,” he says, “on Monday and Wednesday, and on Friday, and on fasts, fish dishes and cakes with butter with wood and nuts, and with flax, and with hemp are prepared for the royal household; and on During Great and Dormition Lents, dishes are prepared: raw and warmed cabbage, milk mushrooms, salted saffron milk caps, raw and warmed, and berry dishes, without oil, except on Annunciation Day - and the king eats during those fasts, a week, on Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday, once a day, and drinks kvass, and on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday during all fasts he does not eat or drink anything, except for his own and the Tsarina’s, and the Tsarevich’s, and the Tsarevna’s name days.”

However, despite such fasting and special moderation, about seventy dishes were served at the sovereign’s ordinary table on meat and fish days, but almost all of these dishes were given to the boyars and other persons to whom the sovereign sent these servings as a sign of his favor and honor. For close people, he sometimes himself chose a well-known favorite dish. First they served cold ones and biscuits, various vegetables, then fried ones, and then stew and fish soup or ear soup.

The order and ritual of the room table was as follows: the table was set by the butler and the housekeeper; they laid out a tablecloth and set out bowls, i.e., salt pan, pepper shaker, vinegar pot, mustard plaster, horseradish pot. In the nearest room, in front of the dining room, there was also a table set for the butler, the actual food stand, on which the food was placed before it was served to the sovereign. As a rule, each dish, as soon as it was released from the kitchen, was always tasted by the cook in the presence of the butler or solicitor himself.

Then the dishes were taken by the housekeepers and carried to the palace, preceded by a solicitor who guarded the food. The housekeepers, serving food on the stern, supplied to the butler, also first tasted, each from his own dish. Then the butler himself tasted the food and handed it over to the steward to bring before the sovereign. The waiters held the dishes in their hands, waiting to be called upon. The food from them was received by the last one, the guardian of the table, the most trusted person, who directly served the sovereign with food and drink.

He tasted each dish in exactly the same way and then placed it on the Tsar’s table. The same thing was observed with wines: before they reached the royal cup, they were also poured and tasted several times, depending on how many hands they passed through. The cup-maker, having tasted the wine, held the cup throughout the entire table, and every time as soon as the sovereign asked for wine, he poured it from the cup into the ladle and first drank it himself, after which he presented the cup to the king. All these precautions were established to protect the sovereign’s health from damage. For wines, a special drinking station was also arranged in front of the dining room, that is, a special table with shelves.

After dinner, the sovereign went to bed and usually slept until vespers, about three hours. At Vespers, the boyars and other officials gathered again in the palace, accompanied by the Tsar, who went to the high church for Vespers. After Vespers, sometimes business was also heard, and the Duma met. But usually the sovereign spent all the time after Vespers until the evening meal or dinner with his family or with his closest people. During this rest, the sovereign’s favorite pastime was reading church books, especially church histories, teachings, lives of saints and similar tales, as well as chronicles. Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich the Terrible was especially famous for such erudition.

In addition to reading, the kings loved lively conversation, loved the stories of experienced people about distant lands, about foreign customs and especially about antiquity. Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich kept old people in the palace who were a hundred years old and loved to listen to their stories about antiquity. These were the so-called mounted (court) pilgrims, highly respected for their pious life and antiquity. They lived near the royal mansion in special department palace and full content and the care of the sovereign. On long winter evenings, the sovereign called them to his room, where, in the presence of the royal family, they narrated about events and affairs that took place in their memory, about long journeys and hiking.

The sovereign's special respect for these elders extended to the point that he himself often attended their burial, which was always celebrated with great celebration, usually in the Epiphany Monastery, in the Trinity Kremlin courtyard. So, in 1669, April 9, the sovereign buried the pilgrim Venedikt Timofeev; At his burial there were: Paisius, Patriarch of Alexandria, Trinity and Chudovskaya archimandrites, ten priests, an archdeacon, eleven deacons, in addition to various clerics and singers. The presence of the tsar at such services was always accompanied by generous alms, which were distributed to the poor, various poor people and in prisons to convicts and prisoners. Alms were also distributed on thirds, nineties, half-sorochinas and sorochinas - days on which funeral services for the deceased were usually held and commemorations were held. The sovereign also generously rewarded the clergy who attended these funerals.

Horse-riding, i.e., palace (Top meant palace) pilgrims were also called riding beggars, among them were holy fools. The queen and the adult princesses also had riding pilgrims and holy fools in their rooms. Deep universal respect for these elders and elders, holy fools for Christ's sake, was based on their holy, God-pleasing life and the pious significance that they had for our antiquity. Society revered them, honored them as prophets and proclaimers God's will, as unflinching and impartial accusers.

The mounted pilgrims sang to the sovereign Lazarus and all those spiritual verses that can still be heard today from the wandering blind. Were still at royal court blind domrachei who sang fairy tales and epics about the heroes of Prince Vladimir, playing the domra, a stringed instrument similar to the balalaika. They also played Russian songs. The Bahari were storytellers, telling songs and fairy tales. The Bahar was almost a necessary person in every wealthy home.

Among the sovereign's most common and favorite pastimes was playing chess and a related game of checkers. According to foreigners, chess was played in the palace every day. How common and how powerful this game was can be judged by the fact that the palace employed special masters, turners, who were solely engaged in preparing and repairing chess, which is why they were called chess players.

There was a special Amusement Chamber in the palace, in which various kinds of amusements amused the royal family with songs, music, dancing, rope dancing and other “actions.” Among these amusements were merry (buffoons), caterpillars, fiddlers, housekeepers, organists, dulcimer players, etc. . Fools-jesters also lived in the palace, and the queen had fools-jesters - dwarfs and dwarfs. They sang songs, tumbled and indulged in all sorts of fun, which served as considerable amusement to the sovereign family. According to foreigners, this was Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich’s favorite pastime.

Quite often the sovereign spent time looking at various works goldsmiths, jewelers or diamond makers, icon painters, silversmiths, gunsmiths and in general all artisans who made anything to decorate the royal palace or for the sovereign’s own use. In winter, especially on holidays, the kings loved to watch the bear field, that is, the fight between a hunter and a wild bear. In early spring, summer and throughout the fall, they often traveled to the outskirts of Moscow for falconry. This fun, beloved of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, often began in the morning, before lunch, and continued after lunch until the evening. In general, the emperor spent the summer mostly in country palaces, amusing himself with hunting and farming. In winter, he sometimes went bear or elk hunting himself, and hunted hares.

Finishing the day, after the evening meal, the sovereign again went to Krestovaya and prayed in the same way as in the morning for about a quarter of an hour. When the sovereign was resting alone, the bed servant, who always cleaned and guarded the royal bed, and sometimes the lawyer with the key, who kept the key to the room, and one or two stewards, the closest ones, also lay down in the same chamber.

The pious Moscow tsars made pilgrimages on every church holiday, were present at all rites and celebrations celebrated by the Church throughout the year. These exits gave church festivities even more beauty and solemnity. The Emperor appeared to the people in royal splendor. The most ordinary, almost daily appearances of the tsar to mass and in general to church services on well-known holidays were nothing else; as royal processions, which were therefore often announced, depending on the importance of the festival, by a special ringing of bells, which was called a day off. An old record about this says that “when the tsar goes to pray for holidays in the Kremlin, in China, in the White Tsar’s city, in monasteries and cathedrals, and in secular parish churches, and at that time there is one ringing for the sovereign tsar, and three ringings for the holiday , where is it going"

The sovereign usually went to mass on foot, if it was close and the weather permitted, or in a carriage, and in winter in a sleigh, always accompanied by boyars and other servants and courtyard officials. The splendor and richness of the sovereign's exit clothes corresponded to the significance of the celebration or holiday on the occasion of which the exit was made, as well as the weather conditions on that day. Regarding outer clothing, in the summer he went out in a light silk opashne (long-brimmed caftan) and in a golden hat with a fur trim: in winter - in a fur coat and in a gorlat (fur) fox hat; in the fall and generally in inclement, wet weather - in single-row cloth.

Under the outer clothing there was the usual indoor attire, a zipun worn over a shirt, and a casual caftan. In his hands there was always a unicorn staff, made of unicorn bone, or an Indian one made of ebony, or a simple one made of Karelian birch. Both staves were decorated with expensive stones. During major holidays and celebrations, such as the Nativity of Christ, Epiphany, Palm Week, Bright Resurrection, Trinity Day. Dormition and some others, the sovereign put on the royal attire, which included: a royal dress, actually purple, with wide sleeves, a royal caftan, royal hat or a crown, diadem or barma (rich mantle), pectoral cross and baldric placed on the chest; instead of a staff, a royal silver staff.

All this shone with gold, silver and expensive stones. The very shoes that the sovereign wore at this time were also richly lined with pearls and decorated with stones. The heaviness of this outfit was undoubtedly very significant, and therefore in such ceremonies the sovereign was always supported by the arms of the steward, and sometimes the boyars from his neighbors. The one who was waiting for the sovereign was also dressed more or less richly, depending on the celebration and, accordingly, the clothes of the sovereign. To do this, an order was given from the palace about what dress to wear when leaving. If the boyar was insufficient and did not have rich clothes, then at the time of his exit such clothes were given to him from the royal treasury. Subsequently, under Tsar Fyodor Alekseevich, even a special decree was issued, which prescribed which particular lord's and lord's holidays and what dress to wear during royal appearances.

During the procession, the retinue was separated in rows, people of lower ranks walked ahead, according to seniority, two or three people in a row, and the boyars, Duma and close people followed the sovereign. At all exits, among the royal retinue there was a bed attendant with various items that were required at the exit and which were carried by the bed attendants for the bed attendants, namely: a towel or scarf, a chair with a headboard or cushion on which the sovereign sat; foot, a type of carpet on which the sovereign stood during service; a sunshade or an umbrella that protected from the sun and rain, and some other items, depending on the requirement of the exit.

When the sovereign went out on pilgrimage to the parish or monastery church, a special place was carried in front, which was usually placed in churches for the royal coming. It was upholstered in red cloth and satin, on cotton paper with silk and gold braid. The solicitors generally served the sovereign, accepting, when necessary, a staff, a hat, etc. On small outings, they brought out only a towel (scarf) and a warm or cold footstool, depending on the time of year.

Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich went out to mass, accompanied by bells. One eyewitness describes a similar exit (1565) as follows: having dismissed the ambassadors, the sovereign gathered for mass. Having passed through the chambers and other palace chambers, he descended from the palace porch, speaking quietly and solemnly and leaning on a rich silver gilded staff. He was followed by more than six hundred retinues in the richest clothes. He walked among four young men, thirty years old, but strong and tall: these were bells, the sons of the noblest boyars; two of them walked in front of him, and the other two behind him; but at some distance and at equal distance from him.

All four of them were dressed the same: on their heads they had high caps made of white velvet, with pearls and silver, lined and trimmed around with large lynx fur. Their clothes were made of silver fabric, with large silver buttons, right down to their feet; it was hit by ermines; on the feet are white boots with horseshoes; Each one carried a beautiful large ax on his shoulder, glittering with silver and gold.

In winter, the sovereign usually went out in a sleigh. The sleigh was large, elegant, that is, gilded, painted and upholstered in Persian carpets. In this case, the driver or coachman was a steward from nearby people; but since in the old days they rode without reins, the driver usually sat on horseback, the other nearby steward stood on a bump or in the back, this is how Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich usually rode. Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich rode out more magnificently: at his sleigh, on the sides of the place where the sovereign was sitting, stood the noblest boyars, one on the right, the other on the left; near the front shield of the sleigh stood nearby guards, also one on the right side, and the other on the left; Boyars and other dignitaries walked behind the sleigh near the sovereign. The entire train was accompanied by a detachment of archers, numbering one hundred people, with batogs (sticks) in their hands “for crowded conditions.”

On December 24, Christmas Eve, early in the morning of Christmas, the sovereign made a secret exit, accompanied only by a detachment of archers and clerks of the Tainago Prikaz, into prisons and almshouses, where from his own hands he distributed alms to prison inmates, polonyanniks (prisoners), almshouses, crippled and all sorts of poor people. Along the very streets where the sovereign passed, he also distributed alms to the poor and wretched, who gathered in large numbers even from remote places to such God-loving royal exits. At the same time, as the sovereign visited all prisoners and orphans, proxies from the Streltsy colonels or clerks of the Tainago Prikaz distributed alms at the Zemsky Dvor, also at Lobnago Place, and on Red Square. And we can say that not a single poor person in Moscow was left on this day without royal alms, everyone had something to break their fast, everyone had a “holiday”. Such royal appearances were also made “secretly” on the eve of other major holidays and fasts. On Christmas Eve they took place early in the morning, at about five o'clock.

Having made his morning exit through prisons and almshouses, the sovereign, having changed clothes and rested, walked to the Dining Hut or the Golden Chamber, or to one of the court churches to the royal clock, accompanied by the boyars and all Duma and nearby officials. Then, on the eve of the holiday, the sovereign went to the Assumption Cathedral for Vespers, when during the service the cathedral archdeacon called out the names of many years to the sovereign and the entire royal family. After that, the patriarch with the clergy and the boyar rank greeted the sovereign with many years of happiness.

On the same day, in the evening, when it was already completely dark, the cathedral archpriests and priests and the singing villages came to the palace to glorify Christ, that is, the sovereign’s choirs or the palace choirs themselves, as well as the patriarchal, metropolitan and various other spiritual authorities who had their own special choirs. The Emperor received them in the Dining Hut or in the Front House and gave them a ladle of white and red honey, which was brought in gold and silver ladles by one of his neighbors. At the same time, they also received glory. In the same way, the councilors and singers went to glorify the queen and then to the patriarch, where they also drank copper and received what was glorified. The famous money was given out, depending on the importance and meaning of the clergy: some more, 12 rubles per cathedral, others less, a ruble, half a ruble and even 8 altyns with 2 money, which was 25 kopecks. Tsars Alexei Mikhailovich and his son Fyodor Alekseevich were very fond of church singing and therefore especially favored singers and, in addition to praise, sometimes listened to various other church songs.

On the very feast of the Nativity of Christ, the sovereign listened to matins in the Dining Room or in the Golden Chamber. At 2 o'clock in the afternoon (at 10 o'clock in the morning), while the gospel for the liturgy began, he went out to the Dining Room, where he awaited the arrival of the patriarch with the clergy. For this purpose, the Dining Room was decorated with a large outfit, carpets and cloths. The sovereign's seat was placed in the front corner, and next to it a chair for the patriarch. Having entered the Dining Room, the sovereign sat down in his place before the time and ordered the boyars and Duma people to sit down on the benches; nearby people of the lower ranks usually stood.

The Patriarch, during the singing of the festive stichera, preceded by the cathedral clerics, who carried the cross on the misa and St. water and, accompanied by metropolitans, archbishops, bishops, archimandrites and abbots, came to the sovereign in the same chamber to glorify Christ and greet the sovereign on the holiday. The Emperor met this procession in the entryway. After the usual prayers, the singers sang many years to the sovereign, and the patriarch said congratulations. Then both the sovereign and the patriarch sat down in their places. After sitting for a while and then blessing the sovereign, the patriarch and the authorities went in the same order to glorify Christ to the queen, taking the Golden Chamber, and then to all members of the royal family, if they did not all gather to receive the patriarch from the queen. Glorification of the sovereign usually took place in the Golden Chamber, and sometimes in the Faceted Chamber.

Before mass, Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich usually went to the Ascension Monastery to congratulate his mother, the great elder, monk Marfa Ivanovna.

Having dismissed the patriarch, the sovereign in the Golden or in the Dining Room put on royal attire, in which he marched to the cathedral for mass. All the courtyard and service ranks who accompanied this exit were also richly dressed in golden caftans. After the liturgy, the sovereign marched to the Palace, where then a festive table was prepared in the Dining Room or in the Zolotaya “for the patriarch, the authorities and the boyars.” This ended the Christmas celebration.

On the day of the Nativity of Christ and on other major holidays, the kings did not sit down at the table without first feeding the so-called prison inmates and prisoners. So, in 1663, on this holiday, nine hundred and sixty-four people were fed in the large prison yard.

On this day, the queen also performed her own rituals in the women's half of the Palace. In the morning, before mass, the courtiers and visiting boyars gathered with her, accompanied by whom she went to her Golden Chamber, received there the glorious patriarch, and then proceeded to the palace church for mass. The visiting boyars, along with their congratulations, according to the old custom, presented the queen with perepechi, a type of rich granular Easter cakes or loaves. In 1663, to Tsarina Marya Ilyinichna and the princesses, greater and lesser, fourteen visiting noblewomen brought four hundred and twenty-six bakes, each with 30 bakes. In the same way, after mass, the queen sent five baked goods from herself and from each princess to the patriarch. At the festival, old women and other women of glory came to the queen from the Ascension Monastery to glorify her. Young princes were sometimes praised by their dwarves.

During the “meat week,” that is, on Sunday before Maslenitsa, after Matins. Our Church performed the Last Judgment.

This action was performed on the square behind the altar of the Assumption Cathedral in front of the image of the Last Judgment, according to a special charter, and consisted of singing stichera, consecrating water and reading the Gospels for four countries, after which the patriarch wiped with a sponge the image of the Last Judgment and other icons brought to acting At the end of the action, the patriarch made the sign of the cross and sprinkled holy water on the sovereign, the authorities and the whole people present at the performance of this rite.

Before leaving for the action early in the morning, three hours before light, the sovereign made a tour of the prisons and orders where the convicts were imprisoned, and all the almshouses where the wounded, paralyzed and young orphans and foundlings lived. There he gave out alms with his own hands; freed criminals. In addition, on the same day in the Palace, in the Golden or in the Dining Room, a table was given for the poor brethren. The Emperor himself dined at this table and with all the rituals festive tables treated his many guests. At the end of the table, he gave monetary alms to everyone from his own hands.

At the same time, according to the royal decree, the prison inmates and all prisoners were fed in the prison yard; in 1664, 1110 people were fed there on that day. From halfway through Maslenitsa, the days of forgiveness began. On “the Wednesday of cheese week, the sovereign visited the city monasteries: Chudov, Voznesensky, Alekseevsky and others, as well as monastery farmsteads, where he said goodbye to the brethren and hospital elders and gave them monetary alms. On Thursday and mainly on Friday, the sovereign traveled to suburban Moscow monasteries, in which he also said goodbye to the monastery brothers and sisters and gave them alms.

In the Novospassky Monastery, sovereigns from the House of Romanov said goodbye at the tombs of their parents. On Friday, and sometimes on Saturday or Sunday, the sovereign, accompanied by the boyars, and the patriarch with the authorities went to the queen for forgiveness. She received them in her Golden Chamber and favored both boyars and visiting boyars, mostly her relatives and in-laws, who came to her, also for forgiveness, at a special call.

On the week of raw food, that is, on the Sunday before Lent, in the morning, before the liturgy, the patriarch with all the spiritual authorities, preceded by the cathedral keymaster, who carried the cross and holy water, came to say goodbye to the sovereign. The Emperor usually received him in the Dining Izba. Having released the patriarch, the tsar performed a ceremony of forgiveness with the ranks of the courtyard and servicemen. On the same forgiven day in the evening, the sovereign, accompanied by secular officials, marched to the Assumption Cathedral, where the patriarch performed the rite of forgiveness according to the rank. After litanies and prayers, the sovereign approached the patriarch and, saying forgiveness, kissed the cross. The spiritual and secular authorities also, speaking of forgiveness, all kissed the patriarch’s cross and then went to the sovereign’s hand.

From the cathedral, the sovereign walked to say goodbye to the patriarch, accompanied by boyars and other officials. At the patriarch’s place in the Cross or Dining Chamber, which was decorated with cloth and carpets for the sovereign’s parish, all the spiritual authorities, that is, metropolitans, archbishops and archimandrites, gathered at that time. The Patriarch met the sovereign on the stairs, sometimes in the middle of the Chamber of the Cross; in this case, the sovereign was met in the entryway by the authorities. Having met, the patriarch blessed the sovereign and, taking him by the arm, went with him to the usual places.

In the entryway of Krestovaya, even before the arrival of the sovereign, a royal drinking station was set up with various foreign grape wines, red and white, and Russian honey, red and white. And, “after sitting for a while,” the sovereign ordered the steward to carry their sovereign drink. There was a farewell treat with wines and meads for all those present. The patriarch treated him, offering it to the sovereign himself.

When these farewell bowls ended, the sovereign and the patriarch sat down on benches in their former places and ordered the authorities and boyars and everyone present in the chamber to leave, while they themselves talked in private about spiritual matters for half an hour.

From the patriarch, the sovereign marched to the Chudov and Ascension monasteries, to the Archangel and Annunciation Cathedrals, where he said goodbye to St. relics and at the coffins of parents. Arriving at the palace, the sovereign in one of the reception chambers said goodbye to the people “in the room,” that is, he favored the hand of the room boyars, duma and generally close people who were granted these ranks “from the room,” that is, from among those who from childhood were constantly with the person of the sovereign. At the same time. He said goodbye to all ranks and officials of the lower ranks of his Sovereign Court.

In the same way, the rite of forgiveness was performed on this day and in the half of the queen, who in her Golden Chamber said goodbye to the closest relatives from the boyars and other ranks and to her entire “court”, favored the hand of mothers, riding boyars, treasurers, bed-maids, craftswomen, movnits, etc.

On the same farewell day, the kings observed another memorable custom: in the morning or evening, the heads of all the Orders reported to the sovereign about “the convicts who have been sitting in what cases for many years.” Based on this report, the sovereign released many criminals, especially those who “were not in great guilt.”

In the first week of Great Lent, on Tuesday, after mass, attorneys from thirty-five monasteries came to the palace and presented the sovereign and each member of the royal family from each monastery with bread, a dish of cabbage and a mug of kvass. Having ordered the acceptance of this usual tribute, the sovereign granted favors to the monastery cellar solicitors, that is, he ordered them to be given wine, beer and honey from his cellar.

It must be said that monasteries have always been famous for their skillful baking of bread and excellent preparation of kvass and cabbage.

Under Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich, the monastery of Anthony of Siisk (Arkhangelsk province, in the Kholmogory district) was famous for its kvass, so the sovereign sent his bakers and brewers there “to teach kvass jam.”

In the first week of Lent, on Wednesday or Saturday, and sometimes on another day, after mass, in the Dining Izba, the sovereign himself distributed the so-called circles to the boyars and other ranks, that is, slices of kalach, foreign grape wine and various sweets , fruits dried and boiled in sugar, honey and molasses.

For the feast of the Annunciation of the Most Holy Theotokos, the sovereign often “fed the poor” in his chamber mansions, that is, in the Room and the Antechamber. So, in 1668, “sixty beggars were fed in the Room and in the Front, and the great sovereign gave them alms from his sovereign hands: ten people two rubles, fifty people one ruble.”

Before the onset of the Bright Day, the sovereign again visited prisons and almshouses, distributed alms everywhere to the poor and prisoners with a generous hand, freed criminals, and ransomed the poor. On Wednesday of Holy Week, the Tsar went to the Assumption Cathedral for “forgiveness.” On the same day, at midnight, the sovereign made his usual appearance for “alms distribution.” The same exits took place on Good Friday and Saturday. On these same days, the sovereign also went around some monasteries, especially the Kremlin ones, for forgiveness; He always went to Voznesensky and the Archangel Cathedral to say goodbye at the coffins. On Saturday after the liturgy, the patriarch sent the sovereign from the cathedral consecrated circles of bread and whole bread and Fryazhsky (foreign grape) wines.

At the eve of Bright Day, the Emperor listened to the Midnight Office in the Room. Since the time of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, the sovereign’s chambers have been located in the Terem Palace: there was also a Room, now known as the “Throne Room”.

At the end of the midnight office, in this Room the ritual of royal contemplation was performed, which consisted in the fact that all the highest courtyard and service ranks and some officials of lower ranks, with the special favor of the sovereign, entered the Room to “see him, the Great Sovereign, with bright eyes.” . The boyars and all other dignitaries and service people had to appear at this time in the palace and accompany the sovereign to matins and then to mass. But not everyone was granted the grace to see the bright eyes of the sovereign in the Room. At that time, there was free entry there, except for people close to or in their household, boyars and “non-roomed”, Duma nobles, Duma clerks.

Officials of lower ranks were admitted, by special permission of the king, by choice, and entered the Room by order of one of the closest people, usually the steward, who at that time stood in the Room at the hook and let them in according to a list of two people. All other officials were not allowed into the Room at all. The steward from the top, that is, starting from the eldest on the service list, saw the sovereign's eyes and struck with their foreheads already at the exit in the vestibule in front of the Front (to the present refectory).

All the junior stewards and solicitors, who were in golden caftans, beat the sovereign in front of the vestibule, on the Golden Porch and on the square in front of the Church of the All-Merciful Savior (which is behind the Golden Lattice), and who did not have golden caftans, they waited for the royal exit to Bed and on the Red Porch. Officials were admitted to all places, especially those close to the sovereign’s chambers, with a special grant that corresponded to the reward for their service.

While the boyars and other officials entered the Room, the sovereign sat in chairs in a standard silk caftan, worn over a zipun.

Each of those who entered the Room, seeing the bright eyes of the sovereign, beat his forehead, that is, bowed to the ground before him and, having given the petition, returned to his place.

The rite of royal contemplation ended with the appearance of the sovereign for matins, always to the Assumption Cathedral. The sovereign himself and all the ranks to the last at this time were in golden robes. Anyone who did not have such clothes was not allowed into the cathedral.

During Matins, after the verses of praise, the sovereign, according to custom, venerated the gospel and images and “kissed on the lips” with the patriarch and with the highest spiritual authorities, and bestowed upon others his hand, and also bestowed red eggs on both. and all the ranks that were in the cathedral also venerated the shrine, approached the patriarch, kissed his hand and received either gilded or red eggs:

the highest - three, the middle - two, and the youngest - one egg. Having made Christ with the clergy, the sovereign marched to his royal place at the southern doors of the cathedral, where he shook hands and distributed eggs to the boyars and all ranks to the last. The sovereign distributed goose, chicken and wooden eggs, three, two and one at a time, depending on the nobility of the persons. These eggs were painted in gold with bright colors in a pattern, or with colored grasses, “and in the grasses there were birds and animals and people.”

From Matins, from the Assumption Cathedral, the sovereign first marched to the Archangel Cathedral, where, observing the ancient custom, he made Christ with his parents, that is, he bowed to their coffins. Then, through the Annunciation Cathedral, where he christened himself with his confessor, kissed him on the mouth, the sovereign marched to the palace. There, in the Golden Chamber, he received the patriarch and the authorities, who came to glorify Christ and congratulate him, after which, with the patriarch and authorities, accompanied by boyars and other officials, he marched to the queen, who received them in her Golden Chamber, surrounded by mothers, servants and visiting noblewomen . The Tsar made Christ with her, the Patriarch and the spiritual authorities blessed the Tsarina with icons and kissed her hand. The secular ranks, striking their foreheads, also kissed her hand. At this time, both hands of the empress were supported by boyars from close relatives.

The Emperor listened to early mass for the most part in one of the palace churches, together with his family, the queen and children. Towards the end, the sovereign usually went to the Assumption Cathedral. At the end of the mass, the patriarch blessed the sovereign tsar with Easter and an egg and ate it himself with the sovereign and then served it to the boyars and authorities and priests.

Having come from mass, the sovereign in the queen's chambers greeted his hand and distributed colored eggs to mothers, riding (court) noblewomen, treasurers and bed-maids. Then he favored his courtyard people and, in general, all the lower courtyard servants.

While performing the cherished rite of Christhood with all ranks, the sovereign found time to visit the unfortunate prisoners in prisons, to whom he also said “Christ is Risen!” and gave them alms. In addition, on this day the sovereign provided food for the poor brethren in the Tsarina’s Golden Chamber.

On the next or third day of the holiday, and most often on Wednesday of Bright Week, the sovereign received in the Golden Chamber, in the presence of the entire royal rank, the patriarch and spiritual authorities, who came with gifts. The Patriarch blessed the sovereign with an image and a golden cross, often with St. relics, gave him several cups, gold and non-gold velvets, satin, damask or other materials, then three forty sables and one hundred gold. The queen, princes and princesses received the same gifts, only in smaller quantities and of less value.

In addition to the image, cross, cups and velvets, the patriarch presented the queen with two forty sables and also one hundred gold pieces; to the princes forty sables and fifty gold pieces; the princesses received forty sables and thirty gold pieces. Other ecclesiastical ranks offered gifts according to their wealth, whatever they could. The outstanding gift from all rich or wealthy persons was gold (coin).

The Trinity-Sergius Monastery offered its product, various wooden utensils, spoons, cups, jugs, glasses, etc., sometimes painted with paints and gold. Others, poorer, offered bread, honey, kvass and, most importantly, a blessing in the image.

But, in addition to more or less significant spiritual authorities and monasteries, at that time all the white authorities with images came to the Emperor in general, and from the monasteries the black authorities also came with images, “and with bread, and with kvass.”

At the same time, with the clergy, the eminent man Stroganov, guests from Moscow, guests from Velikago Novgorod, Kazan, Astrakhan, Siberia, Nizhny Novgorod and Yaroslavl, as well as hundreds of merchants came to the sovereign with gifts.

On the day of the Origin of the Honest and Life-Giving Cross of the Lord, August 1, there is always a religious procession on the water. On the eve of this day, the sovereign went to the Simonov Monastery, where he listened to Vespers and on the holiday itself, Matins and Mass. Opposite the monastery, on the Moscow River, a Jordan was built at this time, just as on the day of Epiphany. The Tsar, before the procession of the cross and accompanied by the boyars and all the dignitaries, went out “to the water* and after the consecration, solemnly plunged into the Jordan, bathed in the consecrated water for health and salvation, for which purpose he laid on himself the three cherished crosses. Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich laid the cross of Peter the Wonderworker and blessed by his grandmother Martha Ivanovna, the mother of Tsar Mikhail Feodorovich. Tsars often took a ceremonial bath in the Jordan in country villages, in Kolomenskoye, on the Moscow River, and in Preobrazhenskoye, on the Yauza.

When the time came for the sovereign or the heir to the state to marry, then their daughters-maidens from all the families of the service, that is, the military nobility, were chosen as brides. For this, the Tsar sent letters to all cities and all estates with the strictest instructions that all patrimonial landowners should immediately go with their daughters to the city to the appointed city governors, who should look at their daughters as brides to the Tsar. The main goal The beauty and kindness of her health and disposition were such voivodeship sights.

After the review, all the selected first beauties of the region were included in a special list, with the appointment to come to Moscow at a certain time, where a new review was prepared for them, even more selective, already in the palace, with the help of the sovereign’s closest people. Finally, the chosen one from the chosen ones came to the bridegroom to the groom himself, who also chose his bride after many “tests”. It is said about Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich the Terrible that in order to select a third wife, “brides from all cities were brought to Alexandrova Sloboda, both noble and ignorant, numbering more than two thousand. Each one was presented to him in a special way. First he chose 24, and then 12, from which he chose his bride.

Father of Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich, led. book Vasily, having decided to get married (this was still under his father), announced throughout the state that the most beautiful girls, noble and ignorant, should be chosen for him, without any distinction. More than five hundred of them were brought to Moscow, according to another testimony - 1,500; Of these, three hundred were chosen, out of three hundred - 200, after 100, finally, only 10; From these ten the bride was chosen.

After the election, the royal bride they were solemnly led into the royal special mansion where she would live, and left until the time of the wedding in the care of courtyard boyars and bed-women, faithful and God-fearing wives, among whom the first place was immediately occupied by the closest relatives of the chosen bride, usually her own mother or aunt and other relatives .