The chief of the gendarmes and the head of the III department of His Imperial Majesty's Own Chancellery, Alexander Khristoforovich Benckendorff, was a kind man, but the censor Petrov, whom he summoned to his house 16 on the Fontanka Embankment, did not suspect this: the most unpleasant rumors were circulating about Count Benckendorff. Ivan Petrov was seriously afraid that in Kochubey’s former mansion he might be flogged...

✂…">

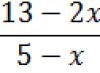

In St. Petersburg they knew well how this was done. The future victim is allegedly received by Benckendorff himself: he is polite and courteous, and the unfortunate man is offered a comfortable chair. The Count sits opposite and gently reproaches the guest for the fact that his behavior is contrary to the views of the government - they recall an inappropriately told “sweetheart” joke or frivolous gossip. And then the count presses a button hidden in the armrest of his chair, the floor opens under the guest, and he falls to the middle of his torso - below, two hefty gendarmes with rods pull down the visitor’s pants and begin to flog, and Alexander Khristoforovich interrogates: from whom, they say, did you hear the harmful a fable about the amorous adventures of the sovereign, who was told that they steal at customs and that the St. Petersburg police share a share with the thieves? They rumored that ladies were also subjected to this treatment - they even wrote about it in English newspapers...

Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf, 1783-1844

Portrait by D. Dow, 1830s

Vorontsov Palace-Museum Alupka. Ukraine.

On July 16, 1843, censor Petrov waited a long time for the count to receive him. Two adjutants in blue gendarmerie uniforms were on duty in the reception area, and under their gazes Ivan Timofeevich became embarrassed. Finally, the office doors opened, and the well-known scandalous novels actress Nymphodora Semenova Jr.: her hair is disheveled, there is a bright blush on her cheeks. Petrov noticed that Semyonova’s dress was not quite in order. Another ten minutes passed, he was invited to enter, the censor with a wildly beating heart crossed the threshold of the office. At a large table littered with papers sat a gray-haired and sliver-thin old man. The chief of gendarmes politely stood up and pointed to the chair opposite him. The censor froze in place, as if the soles of his shoes were glued to the type-setting varnished parquet floor.

Thank you, Your Excellency. I'd rather stand...

The general looked at Ivan Timofeevich in surprise:

Take a seat, do me a favor. Otherwise I’ll have to get up too, and I’m not at the age and rank to talk to you while standing...

Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf

lithograph of Paul based on a portrait by an unknown artist.

Ivan Timofeevich, confused and blushing, spoke of the greatest respect for the general, but he flatly refused to sit down. The chief of gendarmes insisted. They argued gently, and Alexander Khristoforovich, puzzled by the official’s behavior, completely lost sight of why he had called him. I remember that the sovereign ordered him to be reprimanded. But for what? Did he miss something seditious in print? Or maybe he wrote some obscenity himself? (Petrov was a prolific writer.) Petrov stood while the head of the III department sorted through the papers on the table - among them there should be notes related to the censor’s case.

Emperor Nicholas I

Alas, the brown leather folder he was looking for remained at home, on the bureau in the office; there was also a piece of paper with the words: “The sovereign ordered Petrov to be reprimanded for criticizing Polevoy’s play.” The count's wife Elizaveta Andreevna, after Bibikov's first husband, takes the folder in her hands and shakes her head: she knows very well that in the service her husband is without her hands. The folder is handed to the most intelligent footman, he is ordered to “rush as fast as he can to the Fontanka and give the papers to His Excellency.” The footman leaves, and the countess continues to interrogate her husband’s valet, standing at attention in front of her: six months ago, she found the guy with his maid and intimidated the poor fellow, threatening to marry the deceived girl, exile to a distant village, or even become a soldier. Now the valet tells her everything he knows about her husband’s affairs. Now he is posting another piece of information, and the Countess is not at all pleased with what she hears. Firstly, it humiliates her as a woman. Secondly, she is afraid that Alexander Khristoforovich will completely undermine his health.

He was terribly tired and scolded himself for acting like a boy. Visits of actress Semyonova - clean water weakness, yielding to the temptations of the flesh. Moreover, Nymphodora only needs his patronage; in the theater she trumps their relationship - who would pass up the girlfriend of the chief of gendarmes for a role or a benefit performance? But this is not a problem, because he does not like Semenova. Trouble - Amalia Krudener, his love and pain, a fragile beauty with the face of an angel and an iron grip.

She has one of the most brilliant social salons in St. Petersburg, a lot of fans and old husband- a diplomat who has lived three quarters of his life abroad. Amalia has huge debts - her husband doesn’t care about them, Benkendorf regularly pays them off. Then she needs him...

The years had taken a toll on him, but he remained the same as he was in his youth, but now a much aged guardsman boy. As before, he trails every skirt, loves his wife and yet cheats on her, and so awkwardly that the whole world knows about it.

The Count stood up and trudged heavily towards the door. We must go home... Again we will have to deceive his wife, whom Benckendorff began to cheat on a year and a half after the wedding, although he married Elizaveta Andreevna out of passionate love.

Baroness Amalia Maximilianovna Krüdener, in her second marriage - Countess Adlerberg, née Countess Lerchenfeld

Benckendorf's adjutants were not mistaken: he did not have long to be the second man in the empire. In 1844, the count fell ill again and was for a long time between life and death. The emperor was grieving; he was afraid of losing “his good Benckendorff.”

The current sovereign, Nicholas, was raised by his mother, who was Benckendorff's patroness, and the initially young Grand Duke looked at military general from bottom to top. In December 1825, Benckendorff was next to the tsar under bullets on Senate Street; during the rebellion in military settlements and the St. Petersburg cholera riot, the count also did not leave Nicholas’s side, and later the tsar was surprised how they were not stabbed to death. When the count felt better, the emperor ordered Alexander Khristoforovich to be given 500 thousand rubles as a reward and sent him to the healing waters in Carlsbad.

This is what the prominent man wrote in his diary statesman Modest Andreevich Korf, who personally knew Benkendorf:

Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf died in full memory. Before his death, he bequeathed to his nephew, his aide-de-camp, Count Benckendorf, who accompanied him, to ask his wife for forgiveness for all the griefs caused to her and asks her, as a sign of reconciliation and forgiveness, to remove the ring from his hand and wear it on herself, which was subsequently done . He bequeathed his entire wardrobe to the valet, but when the count died, the unscrupulous one released only a torn sheet to cover his body, in which the deceased lay not only on the ship, but also for almost a whole day in the Revel Domkirche, until the widow arrived from Fall. The first night, before her arrival, only two gendarmerie soldiers remained with the body lying in this rags, and the whole church was illuminated by two tallow candles! Eyewitnesses told me this. The last rite took place in the Orangery, because there is a Russian church in Fall, but no Lutheran one. The will of the Emperor was conveyed to the pastor to mention in his sermon how fatal he considered it to be for himself. this year, combining in it the loss of a daughter and a friend! The deceased was buried in Fall in a place chosen and designated by him during his lifetime.from here

Grave of Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf

.

The farther the 19th century is from us, the more discoveries we are now making. Everyone for themselves! The teaching of history in USSR schools was at a very good level, but very often heroes were made into villains, and villains into heroes. The current time provides an opportunity to look at the biographies of many famous personalities of the 19th century from a different perspective. “The torturer of A.S. Pushkin” - the count, head of the III department of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery, chief of gendarmes, was, in the apt expression of the very exalted English artist and writer Elizabeth Rigby, who visited the Fall estate in 1840, “ a man who knew and kept all the secrets of Russia "But not only: Alexander Khristoforovich was also a gallant warrior, general, hero of the War of 1812; commandant of Moscow, after Napoleon left the half-burnt and plundered city in disgrace; personal friend Emperor Nicholas I, the only person who could say “you” to the monarch; a traveler(!) who traveled with secret mission by the will of Emperor Alexander I" for the purpose of military-strategic inspection of the Asian and European Russia "and even looked into China; a womanizer who loved beautiful women and who does not deny himself, even if he has a legal wife, to court the opera diva that he likes, or a corps dancer, or a lady from the empress’s court retinue; and he also wrote memoirs - as many as 18 notebooks about the reign of Alexander I and Nicholas I were left to us as a legacy by this man.

Egor Botman Copy from a painting by F. Kruger. Portrait of A.Kh. Benckendorff in the uniform of the Life Guards Gendarme half-squadron 1840

Benckendorff, noble and count family, descended from knights Teutonic Order who received lands in the Margraviate of Brandenburg at the beginning of the 14th century. Centuries later, the Benckendorffs will faithfully serve Russia and for this they will receive honors and glory from the hands of the emperors themselves. Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf, elevated to the title of count in 1832 Russian Empire dignity, laid the foundation for the count branch of this family.

Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf had his own life story, worthy of many articles and books being written about it. A small excerpt from the article Ancient legends of Staraya Vodolaga will tell about Him and Her, about them - the Benkendorf spouses. Well, portraits and engravings will help you see both Him and Her, and those who surrounded “the man who kept all the secrets of Russia”...

___________________

Love story

He

The future head of the Secret Chancellery and the “strangler of freedom” was born into a family close to the throne: his mother was the best friend of Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna, the wife of the heir to the throne, Paul. The boy was born in Montbellian, grew up in St. Petersburg, and was brought up in a private boarding school in Bayreuth. At first he was known as an incredible fighter, and then as a passionate admirer of women, and was forced to leave the boarding school without finishing his studies, precisely for this reason. He was assigned as a junior officer to the privileged Semenovsky regiment. The hero-lover Benckendorff did not distinguish between a society lady, a young servant or a valet's wife, which displeased Maria Fedorovna, who patronized him. It was decided to send the young rogue on an inspection trip along the borders of the Russian Empire. Contrary to expectations, Benckendorf readily agreed, diligently kept a journal of the trip, and with the permission of the leadership, he remained in the Caucasus to volunteer in the Caucasian corps and “improve in the art of war.” From the Caucasus, already awarded two orders, he goes to the island of Corfu to defend the Greeks from Napoleon, then as a diplomat he shuttles between Paris, Vienna and St. Petersburg, not forgetting his love affairs. He returns to Russia with another passion - the famous French actress Mademoiselle Georges. He even thought about marrying her, but she preferred another suitor.

Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf Engraving from watercolor by P. Sokolov

Since 1809, Alexander Benckendorf has been actively involved in hostilities - first in Moldova against the Turks, and then in the Patriotic War of 1812. He led one of the famous “flying” (partisan) detachments, was the commandant of the newly liberated Moscow, participated in the “Battle of the Nations” near Leipzig and the foreign campaign of the Russian army of 1813-1814. He was awarded many orders - both Russian, Swedish, Prussian and Dutch. From the Regent of Great Britain he received a golden saber with the inscription “For the exploits of 1813.”

George Dow Portrait of General A.H. Benckendorff Gallery of 1812 in the Hermitage

A rake, a dandy, a brilliant officer and an experienced womanizer - this is how he came to Kharkov in 1816 on official business. And I heard a half-question and half-statement: “Of course, you will be with Maria Dmitrievna Dunina?” Next, we should give the floor to the descendant of the chief of gendarmes, on the one hand, and the Decembrist, on the other, Sergei Volkonsky: “ He went. They are sitting in the living room; the door opens and a woman of such extraordinary beauty enters with two little girls that Benckendorff, who was as absent-minded as he was amorous, immediately knocked over a magnificent Chinese vase. When the situation became clearer, Maria Dmitrievna found it necessary to collect information. A maid of honor to Catherine the Great and in correspondence with Empress Maria Feodorovna, she turned to no less than the highest source for information. The Empress sent an image instead of a certificate».

She

Who was she - that beauty, because of whom the Chinese vase was damaged, and, seeing whom, Benckendorf, who had seen women in his life, lost his head? Elizaveta Andreevna Donets-Zakharzhevskaya, the daughter of Maria Dmitrievna’s sister, belonged to the same local nobility.

Elizaveta Andreevna Donets-Zakharzhevskaya, after Bibikov’s first husband, is the future wife of A.Kh. Benckendorff

A lovely blond twenty-nine-year-old widow (her husband, Major General Pavel Bibikov, died in the War of 1812, leaving her alone with two daughters), guessing the intentions of the visiting seducer, staunchly defended herself. And he seriously fell in love. Alexander Benkendorf by this time was already thirty-four years old. Since the fortress did not surrender, there was only one way out for the old bachelor - to get married. And Elizaveta Andreevna did right choice: Alexander Benkendorf became a real father for her two daughters - Ekaterina and Elena, who inherited her mother’s beauty and was subsequently considered the first St. Petersburg beauty.

..jpg)

Elizabeth Rigby Spouses Benkendorf - Elizaveta Andreevna and Alexander Khristoforovich

They married in 1817. 10 years later, at its peak career takeoff, Benckendorf buys the Fall manor (the territory of modern Estonia) and builds a castle there, which, he hoped, will become the “family nest” of the Benckendorffs. However, he and Elizaveta Andreevna only have girls - Anna, Maria and the younger Sofia. Either the lack of sons and heirs played a role, or, following the old saying “Gray hair, devil in the rib,” the venerable head of the family again took up the old ways. Elizaveta Andreevna knew about his tricks, but remained silent, not wanting to wash dirty linen in public. She lived in Falle, a place of wondrous beauty. The famous English artist Elizabeth Rigby came there and left their portrait as a souvenir for the owners; Tyutchev stayed there, gaining poetic inspiration, the famous landscape painters Vorobyov and Fricke worked, and the famous singer Henrietta Sontag performed. Emperor Nicholas came to Fall twice and even planted several trees with his own hands. In September 1844, the body of Alexander Benkendorf was brought there - he died on the way home. Elizaveta Andreevna lived another thirteen years. Both of them are buried in Falle.

Women of his life

As mentioned above, Alexander Khristoforovich loved women very much and there were many of them in his life. Moreover, all these women were outstanding and worthy. Starting from the sister of the chief of gendarmes and ending with his daughter...

Sir Thomas Lawrence Portrait of Daria (Dorothea) Khristoforovna Lieven 1814

Liven Daria Khristoforovna (1785-1857) - countess, sister of the chief of gendarmes Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf, agent of the Russian intelligence service. She was educated at the Smolny Institute, after which she was appointed maid of honor Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna, wife of Paul I. In 1800 she married Count Christopher Andreevich Lieven (Khristofor Heinrich von Lieven), as a result of which she was in close relations with the reigning family. Since 1809, she accompanied her husband on his diplomatic assignments, where she began her intelligence career, being in constant correspondence with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Count Karl Vasilyevich Nesselrode (Karl Robert von Nesselrode), for example, the information she collected helped Alexander I correctly formulate the Russian position at the Congress of Vienna in 1814. Her sharp mind and magical charm attracted men - for almost a decade she was the mistress of the Austrian Foreign Minister Klemens Metternich, transmitting information received from him to the Russian Court. During one of the conversations about the successes of the Third Section, Nicholas I expressed his satisfaction to the chief of gendarmes, noting that his “ over time, my sister went from an attractive girl to a statesman”.

Louis Contat and Henri-Louis Riesener Portraits of Mademoiselle Georges, actress of the Comédie Française

Fifteen-year-old Frenchwoman Marguerite-Joséphine Weimer made her debut in 1802 at the famous Comedie Française theater under the pseudonym Mademoiselle Georges, taken from her father's name. Talent, ancient beauty, luxurious figure and gorgeous voice quickly made her the queen of the stage. Her fame was so great that Napoleon himself could not resist the actress, whose mistress Georges was before meeting... with Alexander I. And also our hero, Alexander Khristoforovich, was allegedly attracted to her and, according to legend, it was Mademoiselle Georges who was looking for him in Russia when in 1808 she visited St. Petersburg.

Joseph Stieler Portrait of Amalia Krüdener 1828

Amalia is the illegitimate daughter of Count Maximilian Lerchenfeld and Princess Therese of Thurn-und-Taxis. In 1825 Amalia married in Munich Russian diplomat Baron Alexander Krudener. A passionate admirer of the young baroness was Count A.Kh. Benckendorf. The employees of Section III were languishing under Amalia's yoke. Amalia's influence on Benckendorff was so great that, at her insistence, he secretly converted to Catholicism. According to the laws of the Russian Empire, where Orthodoxy was state religion, such an act was punishable by hard labor. (The secret was revealed only after the death of Alexander Khristoforovich). It was to this woman that he dedicated his beautiful poem F.I., in love with her Tyutchev... "I met you."

M. de Caraman Anna Alexandrovna Benckendorff Engraving of Wittmann from a portrait

Countess Benckendorff Anna Alexandrovna (1818-1900), married Countess Apponyi, the eldest daughter of A. X. Benckendorff. She was the ambassador's wife and lived in Paris, London, and Rome for many years. She had an amazingly beautiful voice and became the first public performer of the Russian anthem “God Save the Tsar!”

On June 25, 1826, six months after the Decembrist uprising, the post of chief of gendarmes was established by the highest order. Of course, the author of the police project, Lieutenant General Benckendorff, was appointed to this post. They tried not to inflate the administrative structures, knowing that the bureaucrats were only getting in the way. Therefore, under the chief of gendarmes there were only sixteen people, who very successfully and effectively managed the peace officers. There are SIXTEEN in total, and how many are sitting on your neck now? Russian people all sorts of supposedly leaders? And there are countless numbers of them.

Emperor Nicholas I

Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf

October 5 (September 23, old style) 1844, returning to Russia from abroad on sea ship on o. Dago, not far from Revel, Alexander Khristoforovich died. This is how Baron Modest Andreevich Korf, who personally knew Benkendorf, wrote about his death: “ Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf died in full memory. Before his death, he bequeathed to his nephew, his aide-de-camp, Count Benckendorf, who accompanied him, to ask his wife for forgiveness for all the griefs caused to her and asks her, as a sign of reconciliation and forgiveness, to remove the ring from his hand and wear it on herself, which was subsequently done . He bequeathed his entire wardrobe to the valet, but when the count died, the unscrupulous one released only a torn sheet to cover his body, in which the deceased lay not only on the ship, but also for almost a whole day in the Revel Domkirche, until the widow arrived from Fall. The first night, before her arrival, only two gendarmerie soldiers remained with the body lying in this rags, and the whole church was illuminated by two tallow candles! Eyewitnesses told me this. The last rite took place in the Orangery, because there is a Russian church in Fall, but no Lutheran one. The will of the Sovereign was conveyed to the pastor to mention in the sermon how fatal he considers this year to be for himself, due to the loss of his daughter and friend! The deceased was buried in Fall in a place chosen and designated by him during his lifetime.."

Grave of A.Kh. Benckendorf at his estate in Falle, Estonia

.+%D0%A0%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%BC%D0%B5%D1%80+43,5%D1%8535,5+%D1%81%D0%BC.+%D0%9B%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%BD+Colnaghi,+1824.jpg)

Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf

Russia's past was amazing, its present is more than magnificent, and as for its future, it is beyond anything that the wildest imagination can imagine.

Alexander Benkendorf

Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benckendorff (born Alexander von Benckendorff) (1782-1844) - Russian military leader, cavalry general; chief of gendarmes and at the same time Chief boss III department of His Imperial Majesty's Own Chancellery (1826-1844).

Brother of Konstantin Benckendorff and Dorothea Lieven.

Came from noble family Benckendorffov.

Botman, Egor Ivanovich - Portrait of Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf

FIRST GENDARME OF RUSSIA

Traces government activities The Benckendorffs are led to the Kaluga province, where they were family estates. The most famous of the gendarmes of Russia was the eldest of four children of the general from the infantry, the Riga civil governor in 1796-1799, Christopher Ivanovich Benckendorff and Baroness Anna-Juliana Schelling von Kanstadt.

His great-grandfather, the German Johann Benckendorff, was burgomaster in Riga and elevated to the dignity of nobility by King Charles of Sweden.

His grandfather Johann-Michael Benckendorff, in Russian Ivan Ivanovich, was lieutenant general and chief commandant of Revel. The Benckendorffs' approach to the Russian throne is connected with him, who died with the rank of lieutenant general.

After the death of Ivan Ivanovich, Catherine II, in memory of 25 years of “unblemished service in the Russian army,” made his widow Sophia Elizabeth, née Riegeman von Löwenstern, the teacher of the Grand Dukes Alexander and Konstantin Pavlovich.

She remained in this role for four years, which was enough to play a big role in the fate and career of her future grandchildren.

Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf was born on June 23, 1783. Thanks to the palace connections of my grandmother and mother, who came to Russia from Denmark in her retinue future empress Maria Fedorovna, his career was determined immediately.

At the age of 15, the young man was enrolled as a non-commissioned officer in the privileged Semenovsky Life Guards Regiment. His promotion to lieutenant also followed very quickly. In this rank he became the aide-de-camp of Paul I.

However, favorable prospects ties associated with the honorary position of aide-de-camp to the emperor did not last long.

In 1803, the unpredictable Pavel sent him to the Caucasus, which was not even remotely reminiscent of the diplomatic voyages to Germany, Greece and the Mediterranean, where the emperor sent the young Benckendorff.

The Caucasus with its grueling and bloody war with the mountaineers became a real test of courage and the ability to lead people, which Benckendorff passed with dignity. For the cavalry attack during the storming of the Ganja fortress he was awarded with orders St. Anna and St. Vladimir IV degree.

Caucasian battles soon gave way to European ones. In the Prussian campaign of 1806-1807 for the Battle of Preussisch-Eylau, Benckendorff was promoted to captain and then to colonel.

Then followed Russian-Turkish wars under the command Cossack chieftain M.I. Platov, the hardest battles during the crossing of the Danube, the capture of Silistria.

In 1811, Benckendorff, at the head of two regiments, made a desperate foray from the Lovchi fortress to the Rushchuk fortress through enemy territory. This breakthrough brings him "George" of the IV degree.

In the first weeks of the Napoleonic invasion, Benckendorff commanded the vanguard of the Baron Vinzengorod detachment; on July 27, under his leadership, the detachment carried out a brilliant attack at Velizh. After the liberation of Moscow from the enemy, Benckendorff was appointed commandant of the devastated capital. During the period of persecution Napoleonic army he captured three generals and more than 6,000 Napoleonic soldiers.

In the campaign of 1813, at the head of “flying” detachments, he defeated the French at Tempelberg, for which he was awarded “St. George” III degree, then forced the enemy to surrender Furstenwald.

Soon he and his squad were already in Berlin. For the unparalleled courage shown during the three-day cover of the passage of Russian troops to Dessau and Roskau, he was awarded a golden saber with diamonds.

Next - a swift raid into Holland and the complete defeat of the enemy there, then Belgium - his detachment took the cities of Louvain and Mecheln, where 24 guns and 600 British prisoners were recaptured from the French. Then, in 1814, there was Luttikh, the battle of Krasnoye, where he commanded the entire cavalry of Count Vorontsov.

The awards followed one after another - in addition to "George" III and IV degrees, also "Anna" I degree, "Vladimir", several foreign orders. He had three swords for his bravery.

He finished the war with the rank of major general. In this rank, in March 1819, Benckendorff was appointed chief of staff of the Guards Corps.

However, the impeccable reputation of a warrior for the Fatherland, which placed Alexander Khristoforovich among outstanding military leaders, did not bring him the fame among his fellow citizens that accompanied the participants Patriotic War.

Portrait of Alexander Khristoforovich Benckendorff by George Dow.

Military gallery Winter Palace, State Hermitage Museum (St. Petersburg)

His portrait in famous gallery heroes of 1812 causes undisguised surprise among many.

But he was a brave warrior and a talented military leader. Although there is a lot in history human destinies, in which one half of life cancels the other. Benckendorff's life is a clear example of this.

He was one of the first to understand what the “ferment of minds” could lead to, the reasoning and thoughts that matured in officer meetings. In September 1821, a note about secret societies ah, existing in Russia, and about the “Union of Prosperity”.

It expressed the idea of the need to create a special body in the state that could monitor the mood of public opinion and suppress illegal activities.

The author also named by name those in whose minds the spirit of freethinking settled. And this circumstance related the note to a denunciation.

A sincere desire to prevent the disorder of an existing public order and the hope that Alexander would understand the essence of what was written was not justified.

What Alexander said about the participation of secret societies is well known: “It’s not for me to judge them.”

It looked noble: the emperor himself was free-thinking, planning extremely bold reforms.

But Benckendorf’s act was far from noble.

On December 1, 1821, the irritated emperor removed Benckendorff from command of the Guards headquarters, appointing him commander of the Guards Cuirassier Division. This was a clear disgrace. Benckendorff, in a vain attempt to understand what caused it, wrote to Alexander again.

Little did he realize that the emperor was offended by this paper and taught him a lesson.

A few months later the emperor passed away. And on December 14, 1825, St. Petersburg exploded with an uprising Senate Square. What became perhaps the most sublime and romantic page of Russian history did not seem so to the witnesses of that memorable December day.

Eyewitnesses write about the city numb with horror, about direct fire volleys into the dense ranks of the rebels, about those who fell dead face in the snow, about rivulets of blood flowing onto the Neva ice. Then - about screwed-up soldiers, hanged officers, exiled to the mines.

But those are the ones tragic days marked the beginning of trust and friendly affection between the new Emperor Nicholas I and Benckendorff.

On the morning of December 14, having learned about the riot, Nikolai told Alexander Khristoforovich:

"Tonight we may both be no more in the world, but at least we will die having fulfilled our duty."

On the day of the riot, General Benckendorf commanded government troops located on Vasilyevsky Island. Then he was a member of the Investigative Commission on the Decembrist case.

The cruel lesson taught to the emperor on December 14 was not in vain. Unlike his royal brother, Nicholas I carefully read the old “note” and found it very useful. After the reprisal against the Decembrists, which cost him many dark moments, the young emperor tried in every possible way to eliminate possible repetitions of this in the future. And, I must say, not in vain. A contemporary of those events, N. S. Shchukin, wrote about the atmosphere prevailing in Russian society after December 14: “The general mood of the minds was against the government, and the sovereign was not spared. Young people sang abusive songs, rewrote outrageous poems, it was considered a fashionable conversation to scold the government. Some preached constitution, other republic..."

Benckendorff's project was, in essence, a program for creating a political police in Russia.

In January 1826, Benckendorff presented Nikolai with a “Project for the construction of high police", in which he wrote about what qualities her boss should have and the need for his unconditional unity of command. Alexander Khristoforovich explained why it is useful for society to have such an institution: "Villains, intriguers and narrow-minded people, repenting of their mistakes or trying to atone for their guilt denunciation, they will at least know where to turn."

The system created by Benckendorff state security was not particularly complicated and practically eliminated possible malfunctions.

All government agencies and organizations were obliged to provide assistance to people “in blue uniforms.” The brain center of the entire system was the Third Department, an institution designed to carry out secret supervision of society, and Benckendorf was appointed its head.

Employees of the service entrusted to Benckendorf delved into the activities of ministries, departments, and committees. To provide the emperor with a clear picture of what was happening in the empire, Benckendorff, based on numerous reports from his employees, compiled an annual analytical report, likening it topographic map, warning where there is a swamp and where there is an abyss.

With his characteristic scrupulousness, Alexander Khristoforovich divided Russia into 8 state districts. Each has from 8 to 11 provinces. Each district has its own gendarmerie general.

In each province there is a gendarmerie department. And all these threads converged in St. Petersburg at the corner of the Moika and Gorokhovaya embankments, at the headquarters of the Third Department.

The first conclusions and generalizations soon followed. Benckendorff points the emperor to the true autocrats Russian state- on bureaucrats.

“Theft, meanness, misinterpretation of laws - this is their craft,” he reports to Nikolai. “Unfortunately, they are the ones who rule...”.

But Benckendorff not only reported, he analyzed the actions of the government in order to understand what exactly irritated the public. In his opinion, the Decembrist rebellion was the result of the “deceived expectations” of the people. Because, he believed, public opinion must be respected, “he cannot be imposed, he must be followed... You cannot put him in prison, but by pressing him, you will only drive him to bitterness.”

The range of issues considered by the Third Department was very wide. They also concerned state security, police investigation, matters of politics, state, and education.

In 1838, the chief of the Third Department indicated the need for construction railway between Moscow and St. Petersburg, in 1841 notes big problems in the field of health care, in 1842 he warned of general dissatisfaction with the high customs tariff, in 1843 - of “murmurs about recruitment”.

After the crash of the imperial carriage near Penza, in which he was traveling with the sovereign, Alexander Khristoforovich became one of the closest dignitaries of Nicholas I, constantly accompanying him on trips around Russia and abroad.

In 1826 he was appointed commander of the Imperial Headquarters, a senator, and from 1831 a member of the Committee of Ministers.

In 1832, the sovereign elevated Alexander Khristoforovich to the title of count, which, due to the count’s lack of male offspring, was extended to his own nephew, Konstantin Konstantinovich. Nikolai had an exceptionally high regard for Benckendorff.

“He did not quarrel with anyone, but reconciled me with many,” the emperor once said. There were few people who corresponded to this description near the Russian tsars.

By nature, Count Benckendorff was amorous and had a lot of novels. About the famous actress Mademoiselle Georges, the subject of Napoleon’s own passion, it was said that her appearance in St. Petersburg from 1808 to 1812 was connected not so much with the tour, but with the search for Benckendorff, who allegedly promised to marry her.

Count A.Kh. Benckendorff with his wife

Rice. Ate. Rigby, 1840

First bad marriage Alexander Khristoforovich married Elizaveta Andreevna Bibikova at the age of 37. The count's second marriage was to Sofia Elizaveta (Sofya Ivanovna) Riegeman von Löwenstern, who was the teacher of the Grand Dukes, the future emperors Alexander and Nicholas.

Alexander Khristoforovich understood everything negative aspects of your profession. It is no coincidence that he wrote in his “Notes” that during a serious illness that happened to him in 1837, he was pleasantly surprised that his house “became a gathering place for the most diverse society,” and most importantly, “completely independent in its position.” .

“Given the position that I held, this served, of course, as the most brilliant report for my 11-year management, and I think that I was perhaps the first of all the chiefs of the secret police who was feared to death...”

Benckendorff never indulged in much joy about the power he had. Apparently, both natural intelligence and life experience and the personal goodwill of the emperor taught him to be above circumstances.

One day, near Penza, at a sharp turn, the carriage in which he was traveling with the sovereign overturned. The crash was serious: the coachman and adjutant were unconscious. Nikolai was severely crushed by the carriage. Benckendorf was thrown to the side. He ran up and lifted the carriage as much as possible so that the emperor could get out. He continued to lie there and said that he could not move: his shoulder was probably broken.

Benckendorff saw that Nikolai was losing consciousness from pain. He found a bottle of wine in his luggage, poured it into a mug, and forced him to drink it.

“Seeing the most powerful ruler sitting in front of me on the bare ground with a broken shoulder... I was involuntarily struck by this visual scene of the insignificance of earthly majesty.

The Emperor had the same thought, and we got to talking about it..."

It is known that Nicholas I volunteered to take over the censorship of Pushkin’s work, whose genius he was fully aware of.

For example, after reading Bulgarin’s negative review of the poet, the emperor wrote to Benckendorff:

“I forgot to tell you, dear Friend, that in today’s issue of “Northern Bee” there is again an unfair and pamphlet article directed against Pushkin: therefore, I propose that you call on Bulgarin and forbid him from now on to publish any criticism of literary works Pushkin".

And yet, in 1826-1829, the Third Department actively carried out secret surveillance of the poet. Benckendorff personally investigated a very unpleasant case for Pushkin “about the distribution of “Andrei Chenier” and “Gabrieliad”.

Benckendorff's widely introduced illustration of private letters in the 1930s literally infuriated the poet.

“The police print out letters from a husband to his wife and bring them to the Tsar (a well-bred and local man) to read, and the Tsar is not ashamed to admit it...”

These lines were written as if in the expectation that both the Tsar and Benckendorff would read them. Hard service, however, powerful of the world this, and it is unlikely that the words of a man whose exceptionalism both recognized slipped past without touching either the heart or consciousness.

Hornbeam in Keile-Joe (Schloss Fall)

Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf died on a ship carrying him from Germany, where he was undergoing a course of long-term treatment, to his homeland. He was over sixty.

The wife was waiting for the count in Falle, their family estate near Revel (now Tallinn). The ship had already brought a dead man. This was the first grave in their cozy estate.

In his study at Fall Castle he kept a wooden fragment left over from the coffin of Alexander I, embedded in bronze in the form of a mausoleum.

Karl Kolman "Riot on Senate Square".

On the wall, in addition to portraits of sovereigns, hung Kolman’s famous watercolor “Riot on Senate Square.”

The boulevard, generals with plumes, soldiers with white belts on dark uniforms, a monument to Peter the Great in cannon smoke...

Something did not let go of the count if he held this picture before his eyes. There may be repentance, or there may be pride for the saved fatherland...

“The most accurate and unmistakable judgment of the public about the chief of gendarmes will be at the time when he is gone,” Benckendorff wrote about himself. But he hardly imagined how distant this time would be...

Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf (1782-1844) - Russian statesman, military leader, cavalry general; chief of the gendarmes and at the same time the Chief Head of the III Department of E. I. V.’s Own Chancellery (1826-1844). Brother of Konstantin Benckendorff and Dorothea Lieven. He came from an old noble family of Benckendorff.

Alexander Benckendorff was born on June 23 (July 4), 1782 (according to other sources - 1781) in the family of Prime Major Christopher Ivanovich Benckendorff and Anna Juliana, née Baroness Schilling von Kanstadt.

He was brought up in the prestigious boarding school of Abbot Nicolas. In 1798, he was promoted to ensign of the Semenovsky Life Guards Regiment with the appointment of aide-de-camp to Emperor Paul I.

In the war of 1806-1807. was under the duty general Count Tolstoy and took part in many battles. In 1807-1808 was at the Russian embassy in Paris.

In 1809, he went as a hunter (volunteer) to the army operating against the Turks, and was often in the vanguard or commanded separate detachments; For outstanding distinction in the battle of Rushchuk on June 20, 1811 he was awarded the Order of St. George, 4th degree.

During the Patriotic War of 1812, Benckendorf was first an aide-de-camp to the emperor and liaised with the main command with Bagration’s army, then he commanded the vanguard of General Wintzingerode’s detachment; On July 27, he carried out an attack in the case of Velizh, and after Napoleon left Moscow and its occupation by Russian troops, he was appointed commandant of the capital. While pursuing the enemy, he was in the detachment of Lieutenant General Kutuzov, was in various matters and captured three generals and more than 6,000 lower ranks.

In the campaign of 1813, Benckendorff commanded a flying detachment, defeated the French at Tempelberg (for which he received the Order of St. George, 3rd class), forced the enemy to surrender the city of Fürstenwald and, together with the detachment of Chernyshev and Tetenbork, invaded Berlin. Having crossed the Elbe, Benckendorff took the city of Worben and, under the command of General Dornberg, contributed to the defeat of Moran's division in Luneburg.

Then, being with his detachment in Northern Army, participated in the battles of Gros Veren and Dennewitz. Having entered under the command of Count Vorontsov, for 3 days in a row he and one of his detachments covered the movement of the army towards Dessau and Roslau and was awarded for this a golden saber decorated with diamonds. At the battle of Leipzig, Benckendorff commanded the left wing of General Winzingerode's cavalry, and when this general moved to Kassel, he was the head of his vanguard.

Then with separate detachment was sent to Holland and cleared it of the enemy. Replaced there by Prussians and English troops, Benckendorff moved to Belgium, took the cities of Louvain and Mechelen and recaptured 24 guns and 600 British prisoners from the French.

In the campaign of 1814, Benckendorff especially distinguished himself in the case of Lüttich; in the battle of Craon he commanded all the cavalry of the gr. Vorontsov, and then covered the movement of the Silesian army to Laon; at Saint-Dizier he commanded first the left wing, and then the rearguard. 1824 when it was in St. Petersburg flood, he stood on the balcony with the sovereign Emperor Alexander I. And he threw off his cloak, swam to the boat and saved the people all day together with the military governor of St. Petersburg M.A. Miloradovich.

Emperor Nicholas I, who was very disposed towards Benckendorff after his active participation in the investigation into the Decembrist case, appointed him on June 25, 1826 as chief of the gendarmes, and on July 3, 1826 as the chief head of the III department of His Imperial Majesty's Own Chancellery and commander of His Imperial Majesty's Main Apartment.

Allegedly, when the Third Department was established, when asked by A.H. Benckendorff about instructions, Nicholas I handed a handkerchief and said: “Here are all the instructions for you. The more you wipe away your tears with this handkerchief, the more faithfully you will serve my purposes!”

The Tsar entrusted Benckendorf with supervision. According to N. Ya. Eidelman, “Bencendorff sincerely did not understand what this Pushkin needed, but he clearly and clearly understood what he, the general, and the highest authorities needed. Therefore, when Pushkin deviated from the right way Luckily, the general wrote him polite letters, after which he didn’t want to live or breathe.”

In 1828, upon the departure of the sovereign to active army for military action against Ottoman Empire, Benckendorff accompanied him; was at the siege of Brailov, the crossing of the Russian army across the Danube, the conquest of Isakchi, the battle of Shumla and the siege of Varna; On April 21, 1829, he was promoted to cavalry general, and in 1832 he was elevated to the dignity of count of the Russian Empire.

Benckendorff was involved in a number of financial ventures. So, for example, A.Kh. Benckendorff was listed among the founders of the society “for the establishment of double steamships” (1836); his share was to be 1/6 of the initial issue of shares, or 100,000 silver rubles at par. According to some reports, he lobbied for the interests of one of the largest insurance companies in Russia in the mid-19th century - the “Second Russian Society from Fire”.

He was a member of the special Committee established for the construction of the Nikolaev railway along with other official representatives of the authorities. The road was built in 1842-1851 between St. Petersburg and Moscow.

In 1840, Benckendorff was appointed to attend the committees on the courtyard people and on the transformation of Jewish life; in the latter he treated Jews favorably.

Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf died on September 23, 1844 on a ship carrying him from Germany, where he was undergoing a course of long-term treatment, to his homeland. He was over sixty. His wife was waiting for him in Falle, their estate near Revel (now Tallinn). The ship had already brought a dead man.

Benckendorff family:

He was married since 1817 to the sister of the St. Petersburg commandant G. A. Zakharzhevsky Elizaveta Andreevna Bibikova (09/11/1788-12/07/1857), the widow of Lieutenant Colonel Pavel Gavrilovich Bibikov (1784-1812), who died in the battle near Vilna. Having been widowed, she lived with her two daughters in the Kharkov province with her aunt Dunina, where she met Benckendorff. Later a lady of state and a cavalry lady of the Order of St. Catherine.

The marriage had three daughters:

Anna Alexandrovna (1819-1899), had in a beautiful voice and was the first public performer of the Russian anthem “God Save the Tsar!”. In 1840 she married the Austrian ambassador Count Rudolf Apponyi (1817-1876), after his death she lived in Hungary on the Lengyel estate. Her daughter Elena was married to Prince Paolo Borghese, owner of the famous villa.

Maria (Margarita) Alexandrovna (1820-1880), maid of honor, was the first wife of Prince Grigory Petrovich Volkonsky (1808-1882) from 1838.

Sofya Alexandrovna (1825-1875), in her first marriage to Pavel Grigorievich Demidov (1809-1858), in her second, from 1859, to Prince S.V. Kochubey (1820-1880).

His two stepdaughters, the Bibikovs, were brought up in the family of A. Kh. Benkendorf:

Ekaterina Pavlovna (1810-1900), Dame of the Order of St. Catherine, was married to Baron F. P. Offenberg.

Elena Pavlovna (1812-1888), one of the first secular beauties, maid of honor, lady of state and chief chamberlain. Since 1831 she has been married to Prince E. A. Beloselsky-Belozersky. Having been widowed, in 1847 she married for the second time the archaeologist and numismatist Prince V.V. Kochubey (1811-1850).

Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf went down in history as a fighter against the Decembrists, the head of the gendarmes, adamant and tough in his decisions. However, even people like him had their vulnerabilities. Benckendorff's weakness was the luxurious beauty Baroness Krüdner. The count in love allowed her everything: control her wealth, connections, and even interfere in the secret affairs of the state.

Climbing by career ladder Alexander Benckendorf took place during the reign of three emperors. At first he entered the service as an aide-de-camp to Paul I, and during the Patriotic War of 1812 he brilliantly commanded troops in battles with the French.

Alexander Benckendorff had his own idea of valor and honor, which often differed from officials of his rank. In 1812, Napoleon's troops approached Moscow. Along with the army, peasants armed with pitchforks and axes stood up to defend the city and its outskirts. Then the landowners sounded the alarm, saying that the workers sensed freedom. The governor of Volokolamsk district sent a report to the capital that a gang of peasants allegedly staged a riot. Benckendorff, who was just fighting the French in that area, was sent to pacify the recalcitrant.

Alexander Khristoforovich flatly refused to suppress the “rebellion” and sent a note to the emperor, in which he described in detail how bravely they fought partisan detachments peasants, and cowardly landowners hid when the enemy appeared. After this, the order to pacify the riot was canceled.

Once again Benckendorff distinguished himself by saving ordinary people during the Neva flood that occurred in 1824. Famous writer and diplomat Alexander Griboyedov wrote: “At that moment the emperor appeared on the balcony. Suddenly one person from his entourage threw off his uniform and rushed straight into the water. It was Adjutant General Benckendorff. Then he saved many from drowning.".

In 1826, Emperor Nicholas I appointed Benckendorff head of the III department of His Imperial Majesty's Own Chancellery or, simply put, chief of the gendarmerie. According to legend, the sovereign handed the count a handkerchief and said: “You will wipe away the tears of orphans and widows, console the offended, stand for the innocent suffering”.

However, Alexander Khristoforovich understood in his own way how to serve. Essentially, he created a police force that had the power to intervene in political affairs at any level. The count himself repeated more than once: “Officials - this class is perhaps the most corrupt. Among them are rare decent people. Theft, forgery, misinterpretation of laws - that’s their trade.”. Those around him were very afraid of the chief gendarme, calling him an octopus who had spread his tentacles everywhere.

It is curious, but in matters of the heart the chief gendarme of the Russian Empire was not as categorical as in the service. He married Elizaveta Andreevna Bibikova, but did not bother himself with being faithful to his wife. His wife knew about his love affairs with theater actresses, but turned a blind eye to it until the count had an affair with Baroness Amelie Krudner.

This lady was the cousin of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. Cousin was illegitimate, so she was married to a rich but elderly baron. Madame Krüdner considered herself very offended and sought solace in the arms of other men.

Amelie was very beautiful and very willing to use all her feminine charm to achieve personal goals. The head of the III department was also caught in her network. Count Benckendorff was so in love with his passion that he allowed her not only to manage his money, but also to interfere in official affairs. From the outside it seemed that the 58-year-old adjutant general did not see that the “young nymph” was prudently and coldly changing his orders at her own discretion.

In the end, the emperor admitted that Benckendorff's affair could cause significant harm state affairs. To expel Baroness Krüdner from the capital, Nicholas I appointed her husband as ambassador to Sweden. But, as it turned out, Amelie had her own plans. On the day of departure, she announced that she was sick with measles. If you have this illness, you must remain in quarantine for 6 weeks. However, the illness did not end in recovery, but in the birth of a child. As it turned out, his father was not his husband, nor Benckendorff, but the Minister of the Court and Appanages, Adlerberg.

For Benckedorff this was a blow, however, he quickly recovered and again took up matters of national importance. Among the gendarme's many informants was his sister.